The Silence of Marichjhapi

Posted by bangalnama on July 6, 2009

http://bangalnama.wordpress.com/2009/07/06/the-silence-of-marichjhapi/

"Millions of babies in pain

Millions of mothers in rain

Millions of brothers in woe

Millions of children nowhere to go"

—Allen Ginsberg (September on Jessore Road)

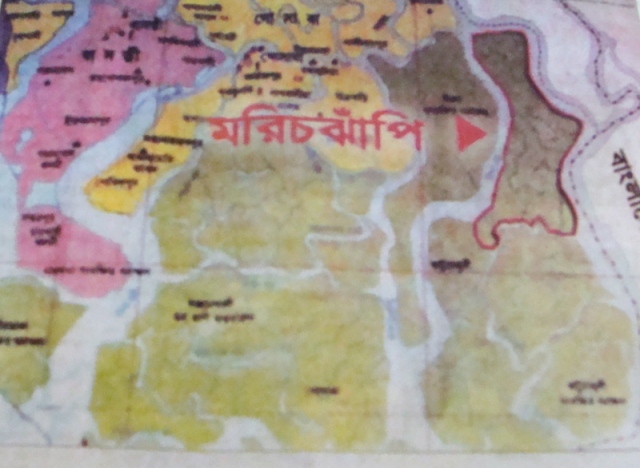

Transnational migration is experienced as a double loss — of origin and of reality; a 'hyperreality', as it were. The representation of identity is, therefore, an ongoing process because immigrant identities are continually being transformed by the journey, their subjectivities being recomposed in 'different practices and sites of experience'. Thus 'home' itself may be experienced in movement and has come to be conceptualized in fluid terms. The immigrants' experience of the present is coloured with a persistent desire for return, a sense of deep nostalgia for their homeland.[1] Therefore, when thirty thousand migrants from Dandakaranya reached the small island of Marichjhapi to the south of Kumirmari of Sundarbans in April 1978, their primary desire was to settle down to conceptualize carefully what could be called 'home' in an altered reality. The otherwise self-sufficient community life that took birth without the cooperation of the midwife named State could not, however, survive the rage of the establishment post 1979. It was then that Marichjhapi was successfully annihilated; silenced beyond a murmur. This piece of semi-academic work shall try its best to document that voice of Marichjhapi before the silence. Marichjhapi, unfortunately has not been as well documented as Nandigram or if we look beyond national boundary, the Nazi Holocaust. However in recent times, owing to the persistent efforts of a fraction of the academia and intelligentsia like Ross Mallick, Annu Jalais, Tushar Bhattacharjee, Mahasweta Devi, Sunil Gangopadhyay and Jagadish Chandra Mandal, Marichjhapi has received a voice. Needless to say I have heavily relied on the available materials and documents to ponder why Marichjhapi Massacre happened and why Marichjhapi is still shrouded in silence.

The factors leading to the Marichjhapi Massacre has to be understood in relation to the long history associated with it that centered on the Partition of Bengal and the intricacies of caste, class and communal differences. More importantly, the Marichjhapi Massacre was ultimately the result of the West Bengal government's politics of policy reversal in the matter of refugee resettlement in forest reserves. All of these have to taken into account while dissecting the history of silence.

The Namasudra Movement of East Bengal had been the most powerful and politically mobilized Dalit movement in India during the colonial period that had kept the Bengal Congress Party in opposition from the 1920s, in alliance with the Muslims. However partition resulted in the loss of bargaining power of the Dalits because, being divided along religious lines of Hindus and Muslims, they became political minorities in both countries. Subsequently the 1950s, '60s and '70s saw the influx of Bengali Hindus from what had become East Pakistan (and later Bangladesh) to West Bengal, who came here with the hope of settling down. They were, however, sent to various uncongenial areas outside West Bengal with the assurance that they would eventually be relocated to West Bengal. The first wave of refugees consisted of traditional upper caste elites. Of the 1.1 million who had arrived by June 1948, 350,000 were urban middle class, 550,000 were rural middle class, a little over 100,000 were agriculturalists, and almost 100,000 were artisans (Chakrabarti 1990, 1). If the richest of them found a haven amongst relatives and friends in Calcutta, the poorer sections squatted on public and private lands and tried to resist eviction. In the 1960s and '70s – and especially after the Bangladesh War of Liberation in 1971, Mujibur Rahman's assassination in 1975 and Zia-ur-Rahman's coming to power – communal agitations started to be directed against the poorest and low caste Hindus who had remained in East Bengal. They now sought refuge in West Bengal.[2]

While their richer counterparts had a roof over their heads and family and friends to provide them with basic amenities of life in Calcutta, the poorer migrants who could not sustain a living in the city were sent to various places practically inhospitable and infertile. Of these, one was Dandakaranya (comprising of parts of Orissa, former Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh in present day Chhattisgarh) – a semi-arid and rocky place where refugees were shunted to; an area culturally, physically and emotionally entirely removed from the migrants' known world.[3] This resulted in extensive protest by the refugees in almost all camps in West Bengal as a mark of dissent against the measures of the Government to send them to Dandakaranya against their will and under compulsion by service of notice on them with the option of going to Dandakaranya or to quit the camp within a period of 30 days. Hunger strikes were started by two batches of refugees of Kalabani and Sarasanka camps in the district of Midnapore on 6th June 1961, and soon it spread like wildfire.

Enter Left Front. They denounced the attempts of the Congress to evict the refugees from West Bengal and promised that when they come to power they would ensure the settlement of the refugees in West Bengal [4] and this would be, in all probability, on one of the islands of the Sundarbans. During the B.C. Roy Government in the 1950s and early '60s, Jyoti Basu, then the leader of opposition, had presented their case in the legislative assembly.

Letter of Shri Jyoti Basu to the State Rehabilitation Minister on the rehabilitation of camp refugees

July 13, 1961.

Sri P. C. Sen

Minister, Refugee, Relief & Rehabilitation,

Government of West BengalDear Sri Sen,

Prolonged hunger-strike by the refugees lasting for more than a month in almost all camps in West Bengal has proved beyond doubt strong reluctance on the part of the refugees to accept the proposal of the Government regarding their rehabilitation in Dandakaranya. As a matter of fact there has been no movement of refugees to Dandakaranya though they have been put to serious hardships and untold sufferings due to stoppage of doles. For more than a month refugees in almost all the camps have been on hunger-strike to voice their protest. It is unlikely that there will be a change in attitude of camp refugees if they are subjected to further hardships and sufferings. Such experiment is also fraught with serious consequences. Left to their own fate these camps families will hardly be able to rehabilitate themselves properly and will be a burden on the State, I, therefore, urge upon you to reconsider the policy of the Government in respect of rehabilitation of camp refugees to prevent further deterioration in the situation.

The primary issues involved now is not continuation of doles to camp refugees for an unlimited period but their early rehabilitation and restoration of doles till that is achieved. We do not think that the rehabilitation of camp refugees in a manner acceptable to them is so very difficult as is often being suggested by the Government. For example, the families now in Sonarpur group of camps may be easily fitted in Herobhanga Second Scheme. Families now in Asrafabad group of camps may also be absorbed in the camp site which is an abandoned rehabilitation colony, the land of which is already in possession of the Government and in Ashoknagar colony if the families are given facility of changing their category. Coopers Camp can be liquidated in its present site if the government implements the present scheme of converting that into a township with some modification. Families now in Gopalpur and Kaksa camps in the District of Burdwan may also be partially absorbed in Durgapur Industrial area and partially in land elsewhere. Families now in the camps in the district of Midnapur may be rehabilitated in Garbeta Scheme. Such illustration may be multiplied. If the refugees are given due facility for rehabilitation through bainanama scheme as well as change of occupational category in addition to the measures suggested above the rehabilitation of all families is now in camps may be completed within a very reasonable period and with much less cost than in places outside West Bengal. The number of such families is now almost half of what it was earlier and many have found rehabilitation in West Bengal although it was stated by the Government that West Bengal has reached a saturation point. I feel, therefore, that the rest may be found rehabilitation here provided there is willingness on the part of the Govt. The enthusiasm that will be generated among the refugees if such a policy is accepted will be no mean an asset for their proper rehabilitation. It is needless to dwell upon the necessity of restoration and continuation of doles during the period prior to their rehabilitation.

It has been made clear from our side times without number that despite the policy set out above for rehabilitation in West Bengal, there may be families who may be willing to go to Dandakaranya and we do not object to their going.

My views on the problem have been briefly outlined in the previous paragraphs. I believe that there is a scope for discussion on the matter for finding a proper solution to it. I am, however, going abroad for a short period, I shall try to meet you later when I come back. But in the meantime I request you to have discussion with the representatives of U. C. R. C., who will seek interview with you.

Yours sincerely,

Sd. Jyoti Basu

The same Left Front had also insisted in a letter to Dr B.C. Roy that no refugee shall be forced out of West Bengal against his wishes. In the meanwhile, CPM leader and erstwhile All India Council of East Pakistan Displaced Persons' General Secretary Samar Mukherjee also sent a letter to Pandit Nehru on 27th July 1961 on the rehabilitation of camp refugees.

Letter of Shri Samar Mukherjee to the Prime Minister on the rehabilitation camp refugees.

Ref No. 24/61 27th July, 1961

From : Shri Samar Mukherji, M. L. A.,

General Secretary, All India Council

of East Pakistan Displaced Persons,

93/1A, Bipin Behari Ganguli Street,

CALCUTTA-12

To : Shri Jawaharlal Nehru,

Prime Minister of India,

NEW DELHI

Sub : Rehabilitation of East Bengal Refugees now in Camp

Sir,

1. A grave situation has developed due to continued hunger strike by groups of refugees in almost all the camps in West Bengal. The hunger strike was first started by two batches of refugees of Kalabani and Sarasanka camps in the district of Midnapore on 6th June last. Since then it has spread to almost all the camps and at present there are about 100 refugees on hunger-strike in different camps.

2. We do not propose to deal with the various problems of other sections of refugees which are nonetheless acute. We like to restrict us here only to the problems of camp refugees because their solution brooks no further delay.

3. The hunger strike by the Camp refugees was started as a mark of protest against the measures of the Government to send them to Dandakaranya against their will and under compulsion by service of notice on them with the option of going to Dandakaranya or to quit the camp within a period of 30 days. It is far from truth that the purpose of the present movement is to continue payment of doles eternally and to delay the liquidation of camps. On the contrary, the main aspect of the present movement is for the demand of their quick rehabilitation in different schemes started or proposed in West Bengal by the Government and through bainanama scheme together with the facility of changing their occupational category.

4. Such demands by refugees are not only realistic but also can be implemented within a very reasonable period and at a cost lower than that for schemes outside West Bengal. This will be borne out by the following illustrations. There are about 1000 families now in Sonarpur group of camps. All these families may be rehabilitated in Herobhanga 2nd scheme which was announced by the Govt. long ago but has not yet been implemented for reasons best know to them. About 600 families of Asrafabad Camp may be rehabilitated at the present site of the Camp which is the site of an unsuccessful rehabilitation Colony as well as in the nearby Ashokenagar Colony where a large number of plots are lying vacant. Coopers Camp may be liquidated in its present site if the Goverment implements the proposed scheme of converting the camp into a township with some modification. Families now in Gopalpur and Kaksa Camps in the district of Burdwan may be absorbed in Durgapore Industrial area. Families now in the camps of Midnapur District may be rehabilitated in Carbeta Scheme where it was proposed to accommodate 1500 familes. But only 350 families have been sent there uptill now. It will not be out of place to mention that in reply to a memorandum submitted in 1958 the West Bengal Government said that about 13,000 families may be settled on fallow lands in Garbata. Such illustrations may be multiplied without any difficulty. We can dare say that if the refugees are given due facility for rehabilitation through bainanama Scheme together with the facility for change of category in addition to the measures stated above their rehabilitation in a manner acceptable to them will not prove so difficult as is often suggested by the Government. It should also be mentioned here that the West Bengal Government stated in 1959 that of the 39,000 bainanamas executed by the camp refugees 21 thousand would be implemented. But not more than 50% of those have been implemented. These along with other measures were suggested to the state Government long ago. If these were adopted in time the camps would have been liquidated long ago and the present undesirable situation would neither have arisen nor the question of rehabilitation of camp refugees in Dandakaranya.

5. It should also be made clear that despite such a policy there might be families who may like to go to Dandakaranya. There can be no objection to that. It will thus be clear that the present movement has nothing to do with opposition to Dandakaranya project as a whole. The movement only opposes sending refugees to Dandakaranya against their will when there is sufficient scope for their rehabilitation in West Bengal in a manner desired by them. It should also be mentioned here that the Chief Minister of West Bengal as well as the Governor of the State gave assurances in categorical terms that no refugee will be sent outside West Bengal against his will.

6. It will be seen that the coercive methods adopted by the Government for sending refugees to Dandakaranya have failed in as much as only 5% of families served with notices have gone to Dandakaranya. A stalemate has reached in respect of rehabilitation of camp refugees. Any further experiment with such a policy is fraught with serious consequences. Left to their own fate these camp families will be hardly able to rehabilitate themselves properly and will ultimately be a burden on the meager resources of the State. A rethinking of the whole question has, therefore, been necessary both for the proper solution of the problem and on human considerations.

7. It is high time that you should intervene immediately into the matter to prevent further deterioration in the situation which will result in loss of life of a few refugees and untold sufferings to many others as well as for a satisfactory solution of the problem.

Yours faithfully,

Sd. Samar Mukherjee

As late as 1974 Jyoti Basu had demanded in a public meeting that the Dandakaranya refugees be allowed to settle in the Sundarbans. The West Bengal Left Front Minister Ram Chatterjee visited the refugee camps and is widely reported to have encouraged them to settle in the Sundarbans, which had been a long held Left Front opposition demand. What was not foreseen by the refugees was that Ram Chatterjee, belonging to a smaller party in the Left Front coalition, was speaking for current policies rather than the imminent shift in policies as soon as the Left Front would be in power.

In 1977 June, the Left Front came into power. During the early part of 1978 the first wave of refugees from Dandakaranya started traveling from Orissa's Malkangiri to West Bengal. They crossed Habra, Barasat, Bali Bridge and finally reached Hasnabad.

Hasnabad Rail Station

Once the number totaled a few lakhs, the then CPM leaders sought to send them back to where they came from. The Left Front government declared that although they had earlier stated that Dandakaranya refugees would be resettled in Sundarbans, under the changed scenario that would not have been feasible. The refugees came to West Bengal from Dandakaranya with the sole intent of settling down in Sundarbans, which was earlier decided to be their new habitat as the Left Front had promised before coming to power. Marichjhapi was one such place. It was the 18th of April, 1978 that more than 10,000 refugees crossed Kumirmari and reached Marichjhapi. They declared that they did not want any aid from the Government towards their resettlement there. They only demanded that they be allowed to stay at Marichjhapi as citizens of the Union of India.

10,000 refugees sold their belongings to disburse for the trip to Marichjhapi. They left Dandakaranya only to find that the refugee policy had changed and many were arrested and returned to the resettlement camps. The remaining managed to slip through police cordons and reach their destination at Marichjhapi island and settlement began.

At Hasnabad, the refugees coming from Dandakaranya camped nearly for two months to find out proper ways of earning, living and to gauge the policy and principles of the State Government towards refugees at Hasnabad. After residing 15/20 days at Kumirmari without any obstruction from local authorities, they entered into the plantation, Bagna, Marichjhapi in 24 Parganas. By their own efforts they established a workable fishing industry, salt pans, a health center, and schools over the following year. [5]

"We started our new lives with a full arrangement of daily consumption such as living house, school, markets, roads, hospital, tube wells, etc. We managed to find out sources of income, also establishing cottage industry such as Bidi factory, Bakery, Carpentry, Weaving factory etc. and also built embankment nearly 150 miles long covering an area of nearly 30 thousand acres of land to be used for fishing, expecting an income of Rs 20 crores per year. That may easily help and enable us to stand on our own feet. Moreover, after one or two years washing by rain water, preventing saline water to flow over those lands will yield a lot of crops such as paddy and other vegetables.

……………….We have distributed lands in Marichjhapi amongst six thousand refugee families in the shape of paras, villages and anchals. Nearly a thousand families built their houses in different plots in group system and have been residing there for about a year."

—- Memorandum To The Members Of Parliament When They Visited Marichjhapi

Refugees in Search of Livelihood

Where They Stayed

Marichjhapi School

[1] Naficy Hamid. 1991. 'The Poetics and Practice of Iranian Nostalgia in Exile'. Diaspora, 1(3):285-302

[2] Ross Mallick. 1999. 'Refugee Resettlement in Forest Reserves: West Bengal Policy Reversal and the Marichjhapi Massacre'. The Association for Asian Studies, Vol. 58 (1) (104-125)

[3] Annu Jalais, April 2005. 'Dwelling on Morichjhanpi', Economic & Political Weekly, vol 40 no 17, pp 1757 – 1762; ''Massacre' in Morichjhanpi', Letters to the Editor in EPW (Economic & Political Weekly), June 18 2005 (response to Ashok Mitra).

[4] Economic & Political Weekly, April 1, 1967, p 633

[5]Mehta, Pandey, and Visharat 1979. Mehta, Pandey, and Visharat were Members of Parliament appointed by Prime Minister Desai, despite the objection of the West Bengal government, to visit and investigate Marichjhapi, prior to the eviction.

(To be concluded in the next issue, "Marichjhapi – Uncovering the Veil of Silence".)

-By Jhuma Sen

No comments:

Post a Comment