Indian Holocaust My Father`s Life and Time- Two Hundred NINETY Nine

Manusmṛti - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- 2 visits - 20/08/09en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manusmṛti - Cached - Similar -

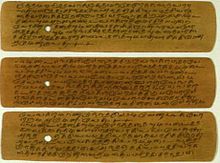

Manu Smriti

www.indianetzone.com › ... › Vedic Civilisation › Vedic Literature - Cached - Similar -

Manusmriti the laws of Manu - Introduction

www.hinduwebsite.com/sacredscripts/laws_of_manu.htm - Similar -

What exactly is written in Manusmriti which encourages casteism in ...

in.answers.yahoo.com › ... › Religion & Spirituality - Cached - Similar -

According to Manusmriti, what r the rules of observing Dharma ...

sawaal.ibibo.com › Others › Miscellaneous - Cached -

StateMaster - Encyclopedia: Manu Smriti

www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Manu-Smriti - Cached -

Manu Smriti: Facts, Discussion Forum, and Encyclopedia Article

www.absoluteastronomy.com/topics/Manu_Smriti - Cached - Similar -

Manu Smriti at AllExperts

en.allexperts.com/e/m/ma/manu_smriti.htm - Cached -

Manusmriti to Madhusmriti

www.infinityfoundation.com/.../h.../h_es_kishw_mythic_frameset.htm - Cached -

Hindunet: The Hindu Universe: A comment on Manusmriti

www.hindunet.com › Scriptures › Vedas - Cached -

Vedas, Dharmasastras and Caste - 1 post - 21 Jul 2001

Get more discussion results

Get more discussion results

'MF Hussain's Departure is a Loss to India' says, Bangalore art communityMyBangalore - 5 hours ago On the other hand, one doesn't need to offend any community, it's not right to make any kind of verbal statement against any religion" Well known ... I love India, but she rejected me: Husain Express Buzz MF Husain is.. Central Chronicle Indian painter M.F.Husain escapes to Qatar Rupee News (blog) Is the magic back?Hindustan Times - Mar 3, 2010 Beyond the elation that springs from banned substances, organised religion and alcoholic stimulants, everyone has moments of euphoria. ... The age of reasonIBNLive.com (blog) - 7 hours ago What if freedom of speech is untouched and untainted by religion? Why does freedom of speech and expression get challenged just at the threshold where ... 'No shift in Pakistan attitude towards India'Express Buzz - - Mar 2, 2010 You can hate India, You can try to out smart us, that is natural we also do the same. But don't love your religion more than your country, this is what is ... Video: India slams Pakistan for not acting against Hafiz Saeed TIME TO WALK THE TALK Calcutta Telegraph Derailed Pak-India peace talks The Nation, Pakistan India plays Saudi tuneExpress Buzz - - Mar 2, 2010 Their religion also says, when a muslim kills a nonmuslim, it is normal to confiscate property and wives and children of a kafir. A muslim has an important ... India, Saudi Arabia to sign about ten agreements Hindustan Times PM offers to walk 'extra mile' with Pak Calcutta Telegraph 'Kingdom a pillar of stability in Gulf' Arab News Cricket is religion in India & Sachin Tendulkar is GodKeeda of Sports (press release) (blog) - - Feb 24, 2010 There cannot be any doubt that if cricket is religion in India, then Sachin Tendulkar is God. •I have seen God. He bats at No. 4 for Indian cricket team ... Is this Sachin Tendulkar's greatest innings ever? Cricketnext.com Sachin's double ton seals series for India Express Buzz Saudi: PM sidesteps role of 'interlocutor'Express Buzz - Mar 3, 2010 By Atheist ALL THESE BASTARDS SPEWING VENOM IN THE NAME OF RELIGION SHOULD BE BUTCHERED FIRST TO ALLOW THE UNHINDERED GROWTH OF INDIA. ... Irrational protestsThe Hindu - Mar 2, 2010 In secular India, the right to freedom of religion is on a par with other fundamental rights. One fundamental right cannot infringe on another fundamental ... Minority forum demands apology from Taslima, Hussain Press Trust of India Taslima Nasreen: Can She Return To Bangladesh Again Gaea Times (blog) Surrender policy in J&KLivemint - 1 hour ago Given the sentiments attached to religion, Husain should have left such themes out of his art. One knows that if there is any portrayal or visual impression ... MF Husain's Exile: Battle For Art Or Religion?CounterCurrents.org - - Feb 27, 2010 In bringing this up, we assume that the dominant religion of India is also what drives its nationalism. Therefore, the 'Save Husain' brigade is equally ... PAINTED OUT Calcutta Telegraph Husain has accepted Qatar citizenship, says son Express Buzz 'I won't blame my father if he accepts Qatar offer' Indian Express |

Religion in India - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_India - Cached - Similar -

Culture of India - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_India - 9 hours ago - Cached - Similar -

Religions in India. Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Sikhism ...

adaniel.tripod.com/religions.htm - Cached - Similar -

The Religions of India

www.healism.com/destinations/india/the_religions_of_india/ - Cached - Similar -

Religion Of India

www.tradewingstours.com/tradetour/india/religion/religion.htm - Similar -

No rejection of religion in India: Dalai Lama: India Today ...

indiatoday.intoday.in/.../Priyadarshan+inks+deal+with+Woodpecker+Pictures.html - Cached -

Science of religion: India Today - Latest Breaking News from India ...

indiatoday.intoday.in/site/Story/81451/.../Science+of+religion.html - Cached -

Information On India: Religions of India

www.tri-murti.com/india/religons.html - Cached -

Manas: Religions of India

www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia/Religions/religions.html - Cached - Similar -

Do we need religion in india today? I think it is eating our ...

sawaal.ibibo.com › Society & Culture › Spirituality & Faith - Cached - Similar -

| religion in india today | |||

| jainism religion india | hinduism religion in india | islam religion in india | major religions in india |

| religion practiced in india | dominant religion in india | main religion india | major religion india |

65 killed in Uttar Pradesh ashram stampede!

Food inflation spikes to 17.87 per cent!

37 women and 26 children were among those killed after they were trampled over by the crowd that had gathered at Kripalu Maharaj's ashram, 60 kms from here, during distribution of food and utensils for the 'Shradh' (post-death rites) of his wife, Sub-divisional Magistrate Kunda Shyama Charan said.

Ramjanki Mandir Stampede Stuns me and I am in Mourning mode but it does not surprise me at all as the Accident in itself has become the Great Escape for those who have Been Excluded, Marginalised, Exploited, Persecuted and are Inflicted with the Greatest Ever man made pandemics of Food Insecurity, Unemployment and Religion is Survival Strategy to boost the Spiritual Moral for Sustenance and the Plight involved. The Accident is a Result in Nature involving a Phenomenon, which is at the same time Economic, Social and Political in Nature. I am browsing the facts exposed by the Media and net but I am dealing with the facts which remain UNCHANGED and Phenomenal in the Valley of India, known as Nuclear shining Hindu India. All the Dead belong to the communities who have no Access to the Global market as they have been Deprived of Purchasing Power and Made to live on DOLE as their Life in itself has been Reduced into dole, Budget allocations for Social Sector without the Land reforms, without Equality and Equal Opportunity, without Inclusion, Without the Annihilation of caste and Class, Hegemony and Dynasty, without Distribution of Assets, do Prove my Point more than Needed!

The rise in the food price index was higher than an annual rise of 17.58 per cent in the previous week.

With food inflation showing signs of impacting the wider economy, the central bank is widely expected to raise borrowing rates at its next policy review given that inflation has already topped its revised end-March forecast of 8.5 per cent.

Farm Minister Sharad Pawar on Wednesday told India's parliament food prices have started easing and would further ease following a good winter crop.

However, the government's decision to raise petrol prices by about 6 per cent and diesel by 7.75 per cent in last week's budget to help increase revenues and cut the budget deficit may prevent food prices from easing.

"Today, truckers have decided to raise the prices. This is basically the second round of impact of the fuel price hike and will have some impact on food prices for the month of February and March," said Sujan Hajra, chief economist with Anand Rathi Securities in Mumbai, before Thursday's data was released.

The government's decision to raise fuel prices for the first time since July has met with anger from both the opposition and ruling coalition allies, underlining the challenge in cutting a near 7 per cent fiscal deficit.

High food prices coupled with a pick in manufacturing and fuel prices are expected to push the headline inflation to double-digits by end-March from 8.56 per cent in January.

In January, the Reserve Bank of India surprised markets with a bigger-than-expected rise in banks' cash reserve requirements, but left the borrowing rates unchanged.

Inflation in manufacturing picked up to 6.55 per cent in January from about 5 per cent in December, a sign that inflationary pressures were spreading to other sectors of the economy.

Inspector General of Police (Allahabad Range) Chandra Prakash said at least 28 people have been injured in the stampede at the ashram in Mangarh area of the district. The injured have been rushed to hospitals in Pratapgarh and Allahabad, about 75 kms from here, officials said.

Eyewitnesses said that many of those killed had fallen into a borewell near the gate. Officials said the district authorities were not given prior intimation about the function. Angry relatives of victims alleged they were not being allowed by the police to look for the bodies of their loved ones.

- Minority forum demands apology from Taslima, Hussain

Kolkata, Mar 03 (PTI) The All-India Minority Forum today demanded that controversial Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasreen and eminent painter M F Hussain "unconditionally apologise in writing" that they would not hurt the religious sentiments of any community.

"We hold that Taslima had delved in anti-Islam writings while Hussain painted Hindu deity Saraswati in the nude in the recent past, which are both condemnable," Forum convenor Maulana Abdur Rahim said here.

"No religion teaches disrespect to other religion and it is undesirable that liberty to write and paint anything is misused," he said, adding Taslima should be sent back to Bangladesh and Hussain, who has accepted Qatar nationality, be brought back to India.

Forum President Idris Ali demanded a CBI inquiry into the recent violence at Shimoga in Karnakata over a purported article written by Taslima.

|

At least 65people were killed and 15 injured today when a gate at Kripalu Maharaj's ashram at Pratapgarh in Uttar Pradesh collapsed during distribution of food on the occasion of a ritual, for which nearly 10,000 people had converged.

On September 30, 2008, nearly 150 devotees were killed and over 60 injured in a stampede at Chamunda Devi temple in Rajasthan's Jodhpur city.

The incident took place when there was a rumour of a bomb going off. More than 10,000 people had turned up at the famous temple for a darshan of the Hindu goddess.

Such a tragedy at the Hindu temple of Naina Devi in Himachal Pradesh on August 3, 2008 had claimed nearly 150 people, mainly women and children, and injured about 230.

On March 27 that year, at least eight people were trampled to death and 10 seriously injured in a stampede at a temple in remote Karila village in Madhya Pradesh.

The stampede at Mandhar Devi temple in Maharashtra in January 2005 when some people fell down on the steps made slippery by devotees breaking coconuts claimed 300 lives.

Among other stampedes, at least six people were killed and 12 injured in July 2008 during the annual Jagannath Yatra in Puri, Orissa. In January 2008, five people were killed at Durga Malleswara temple in Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh.

In October 2007, 11 killed in such a tragedy at Pawagah in Gujarat while in November 2006, four elderly people crushed to death during a stampede at Jagannath Puri, Orissa.

Nealy 40 pilgrims killed, 125 injured in a stampede at Kumbh Mela in Nasik in August 2003.

"New projects need Rs 80,000 crore. The pending projects are there. If there is service tax it will be very difficult to implement them," she said while replying to supplementaries during Question Hour in the Lok Sabha.

Banerjee said she hoped the Finance Minister will waive off service tax levied on the Railways as he had done the

previous year.

"It is very difficult to go for new lines. The Budget has levied Rs 6,000 crore as service tax, I hope the Finance Minister will exempt Railways from the tax as he had done last year," she said.

Banerjee was upset over Mukherjee's budget proposal to bring the Railways in the service tax net.

Rail ministry officials had written to the Finance Ministry seeking withdrawal of service tax on rail freight.

Withdrawing an earlier exemption, the Union Budget 2010-11 has proposed to levy service tax at 10.3 per cent on "service provided in relation to transport of goods by rail" with effect from April 1

Sonia signals support for fuel price rise, to brief allies

Sending a strong message that she was fully behind the government on fuel price hike, Congress President Sonia Gandhi on Thursday praised Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee for deft handling of the Union Budget.

"We have many essential social obligations and to meet them it is necessary to raise resources. I congratulate the Finance Minister for a fine and delicate balancing act, which has bee

Congress President will also talk to allies of the UPA Government on Thursday, and explain to them the party's position on fuel price hike.

Meanehile, Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee, who has cautioned against instant populism, has told party MPs and UPA leaders that correcting distortions in petro good pricing was unavoidable. He also said the time to take bold decisions is "right now".

Mukherjee also referred to the window of opportunity available to the Centre and added that fuel price hike was critical to the economy.

Mukherjee had hiked customs duty on petrol and diesel to 7.5 per cent from 2.5 per cent while excise duty was raised by Rs 1 on non-branded, or normal, petrol and diesel to maintain growth and give the common man spending power.

Mukherjee said he had three options before him: Sit back and do nothing; Go on a borrowing spree; or Restore the duty structure. He said he opted for the third, as the government could not afford to take economically reckless decisions.

Addressing concerns raised by UPA leaders over the decision's impact on the prices of essentials, he said the government has already carried out a back-of-the-envelope calculation.

"The inflationary impact will be a mere 0.41 per cent," he said, adding that an improved crop situation can absorb it.

Meanwhile, the BJP led opposition has decided to halt proceedings in Parliament for the second consecutive day over the fuel price hike and other issues.

PM committed Parliamentary impropriety: Advani

A day after locking horns with Manmohan Singh during the Presidential Address debate, senior BJP leader L K Advani on Thursday said the Prime Minister had breached Parliamentary propriety by making "false" claims that enhanced pension announced for army personnel had been met.

"Advani informed BJP MPs about PM's claim in Lok Sabha on Wednesday that the government had implemented its decision on enhancement of pension to JCOs and Jawans. No JCO or Jawan has received any such orders. This is a very serious matter of Parliamentary impropriety," senior party leader M Venkaiah Naidu told reporters, quoting Advani.

Advani, who is Chairman of BJP Parliamentary Party, was speaking at a meeting of the BJP MPs here. He cited a letter written by Maj Gen (Retd.) Satbir Singh, vice chairman, Indian Ex-Servicemen Movement, where the latter had mentioned the July 6, 2009 order.

Manmohan Singh had intervened several times yesterday while Advani was replying to the Presidential Address in the Lok Sabha, including on the issue of enhancement of pension to ex-servicemen.

Advani had yesterday pointed to Singh's Independence Day speech in which he had referred to steps regarding the demand of ex servicemen relating to 'one rank one pay'.

Singh said whatever promises have been made were delivered by the Government and that Advani "should not create a rift between the Services and the Government".

"Advani said that the Prime Minister should have studied the matter properly and then spoken on it. This impropriety should be taken seriously," Naidu said.

Government had earmarked Rs 2100 crore per year for the benefit of 12 lakh JCOs and jawans.

Advani praised his party MPs for their performance in Parliament on cornering the government on price rise. On the future strategy, he said the Kashmir issue and US "pressure" on India's foreign policy matters should be emphasised by BJP in Parliament.

"Advani said our complaints are not against the US but against our government's tendency to bow under international pressure. The Saghir Ahmed report on autonomy to Jammu and Kashmir gives the impression that the government will buckle under pressure," Naidu told reporters.

The senior BJP leader also said Home Minister P Chidambaram's recent statement on allowing return of Kashmiri militants from Pakistan-occupied Kashmir would lead to "disastrous consequences".

Advani also patted BJP and NDA state governments which had done well in terms of GDP growth.

"The Central Statistical Survey figures show the five top-most states are BJP and NDA-ruled. Gujarat tops the list, followed by Bihar, Uttarakhand and Jharkhand. The fifth is Orissa," Naidu said.

BJP maintained that it had not worked out any floor co-ordination with other opposition parties on taking on the government but had no problems in working with them.

RJD, SP to oppose Women's Reservation Bill

New Delhi The RJD and Samajwadi Party on Thursday remained firm on their opposition to the Women's Reservation Bill which the government has decided to bring in the Rajya Sabha on March 8."We will not tolerate it," Rashtriya Janata Dal supremo Lalu Prasad told reporters outside parliament.

"The country's president is a woman, Lok Sabha Speaker is a woman, Congress president and UPA chairperson is also a woman and they have not come here through the women quota," he said.

Supporting the RJD's stand, Samajwadi Party leader Akhilesh Singh Yadav said "we will not support the bill in the present form as we want that the bill should have provision for OBC".

When it was pointed out that though the opposition was united on the price rise issue, it was divided on the matter of Women's Bill, he said "both the issues are different".

BJD MP Kalikesh Singhdeo, however, said that his party is in favour of the Bill.

Kanpur Bajrang Dal on Saturday said Qatar giving nationality to painter M F Husain was a "win" for Hindutva forces and those who "insult" Hindu religion have no place in the country.

"Husain's painting depicting Hindu deities in a derogatory manner and insulting the religion was not at all acceptable to us," Bajrang Dal Convener Prakash Sharma said.

"It is a win for Hindutva forces because there is no place for such people in the country," he said.

Sharma said any other writer or painter having similar thoughts should opt for citizenship of any other country because "our party will protest against them."

Eminent painter Husain was given Qatar nationality on Wednesday.

Husain was living in exile for the last four years spending most of his time in Dubai after escalation of hate campaign against him by right wing groups over his controversial paintings on Hindu deities.

"Appealing to Muslims (to help in building Ram temple) is an insult to hundreds of kar sevaks who became martyrs during the Ram temple agitation," Sena chief Bal Thackeray said in an editorial in party mouthpiece 'Saamana'.

He made a "sincere appeal" to BJP that it should stick to the Hindutva ideology.

"The Prime Minister of this country says Muslims have the first right over India's resources and 80 crore Hindus tolerate it meekly. Muslims have everything and Hindus don't even have their Ram temple. Things have come to such a level that Hindus have to plead to Muslims (to allow Ram temple)," Thackeray said.

"Gadkari has appealed to Muslims. Exactly to whom has he appealed because the leadership of radical and jehadi Muslims is no longer in India but in Pakistan, where terror outfits wield the remote, dictating Muslims in India what to do and how to behave," the Sena chief, who belongs to Gadkari's home state, said.

Thackeray asked "If permission of Muslims is to be sought for building the Ram temple, why was the temple agitation launched in the first place?"

"Hindus could have fallen at the feet of the Imam of Jama Masjid and got a piece of land for Ram temple. It was easily possible. But Hindus have shed blood for the Ram temple," he said.

63 killed in ashram stampede close to Allahabad

Lucknow: The promise of a free lunch and utensils turned fatal Thursday when 63 people were killed and more than 30 injured in a stampede that broke out when thousands gathered at an Uttar Pradesh ashram for a death anniversary ceremony.

The entry gate of Kripaluji Maharaj's ashram near Kunda town in Pratapgarh district, about 180 km from here, caved in, triggering a stampede that claimed 60 lives and turned the place into a veritable graveyard.

The dead included a large number of women and children.

"Sixty-three bodies had been recovered but more casualties cannot be ruled out as some of the injured were serious and rushed to the Allahabad medical college for specialised treatment," Additional Director General of Police (law and order) Brij Lal said.

The tragedy occurred when thousands of followers had converged at the Bhakti Dham ashram to attend the annual 'bhandara' (free lunch) hosted by Kripaluji Maharaj on the occasion of his wife's death anniversary.

"Thousands of disciples of the godman had made a beeline for the ashram to attend the 'bhandara' and to get freebies like clothes and utensils when the gate suddenly gave way, bringing under its weight a number of people," Lal said.

"People ran helter-skelter in panic, leading to a stampede, that took a heavier toll, turning the whole place into a mass graveyard," he added.

Some devotees alleged that the situation turned worse when the police used batons to disperse the crowds.

Rescue parties were rushed by the state from Allahabad while a top official was flown from Lucknow to personally take stock of the situation and report to Chief Minister Mayawati.

Legislator of the area Raghuraj Pratap Singh, better known as Raja Bhaiya, told IANS over the phone from Kunda: "The number of deaths are bound to rise as a number of the injured are critical."

He criticised the "slow rescue operations" and said: "Although the event has been an annual feature since the death of Kripaluji Maharaj's wife, this time the crowds swelled because of his prior announcement that some utensils would also be distributed along with lunch."

Kripaluji Maharaj could not be contacted as he was stated to be busy supervising the relief work.

IANS

UP tops child rape graph

| Font Size |

Agencies

According to the latest data by the Ministry of Home Affairs for three years, cases of child rape continue to rise as a total of 4,721 cases were registered during 2006, 5,045 in 2007 and 5,446 in 2008 across the country.

Police have arrested 5,489 people in 2006 for their involvement in such crimes, 5,756 in 2007 and 6,363 in 2008.

Madhya Pradesh registered 892 such cases, Maharashtra (690), Rajasthan (420) and Andhra Pradesh (412) in 2008, the data said.

A total of 411 such cases were registered in Chhattisgarh, 301 in Delhi, 215 in Kerala, 187 in Tamil Nadu, 129 in West Bengal, 106 in Punjab and 104 in Tripura, it said.

Whereas, Gujarat has registered 99 cases, Karnataka 97, Bihar 91, Haryana 70, Himachal Pradesh 68, Orissa 65 and Goa 18.

"According to the Constitution, police and public order is the State subject that is why the primary responsibility of prevention, detection, registration, investigation and prosecution of crimes, including crimes against children, lies with the State governments or Union territory administrations," a Home Ministry official said.

However, the condition in northeastern states was slight better as compared to their counterparts. Eleven cases came to light in Arunachal Pradesh, 12 in Sikkim, 18 in Mizoram, 22 in Manipur, 27 in Assam and 34 in Meghalaya.

According to the data, no such cases were registered in Nagaland, Daman and Diu and Lakshadweep. Besides, ten cases were filed in Chandigarh, nine in Uttarakhand, eight each in Jharkhand and Andaman and Nicobar Islands, five in Jammu and Kashmir, four in Puducherry and three in Dadra and Nagar Haveli.

Out of the total registered cases, 1,177 people were convicted for their offence during 2008. In 2007, 1,210 were convicted for their crime as against 963 in 2006, the data said.

Kashmiri terror groups thriving under Pak patronage: Report

| Font Size |

ANI

Lahore Defence Minister A K Antony's claim that 42 terror training camps were still operative in Pakistan was backed by a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) report which said that militant training camps are once again being established in Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK) and recruitment is also on the rise in the Punjab province.

"It looks evident now that the Kashmiri militant groups are once again working under the 'patronage of the Pakistani establishment agencies'," the BBC said.

The report said that following the 9/11 attacks in the US, India and Pakistan tried to develop peace between them and it was widely believed that Islamabad would stop supporting militancy as it sought better relations with its 'nuclear-armed neighbour.

"But this has changed once again. Since 2009, militant activity has been on the rise in the Kashmir region. The Pakistani government denies any knowledge of Kashmir militant groups increasing their activities and says the militant groups in Kashmir are operating on their own," the report said.

It is pertinent to mention here that Speaking during the Operation Vayu Shakti 2010 programme organized at Pokhran, Rajasthan last week, Antony had said "Our real concern is existence of terror camps intact across the border after 26/11 attack. There are 42 terror camps. And there has been no serious effort to dismantle these camps."

Bhindranwale T-shirts, Made in China, sold in Punjab

Harpreet Bajwa

Youths in villages and towns of the state can be seen sporting bright yellow T-shirts, emblazoned with huge photos of Bhindranwale carrying an AK-47 rifle. And the paraphernalia is being openly sold in prominent markets in Jalandhar, Patiala, Amritsar, Ludhiana and even Delhi.

The numbers are surprising. Sukhdev Singh, a shopkeeper in Amritsar, claims to have sold 1.8 lakh calendars with Bhindranwale's photos, each priced at Rs 20. He claims that the rush is unabated, something which has prompted the Chinese to enter the market.

"More memorablia has been introduced in the market as watches, key chains and car stickers. The Chinese-made T-shirts are selling at Rs 170 each as compared to the Indian-made ones, which are priced at Rs 350 each. Similarly Chinese key chains and watches with Bhindranwale's photo on the dial are available at one-fifth the price of same products of Indian make. Stickers are available in seven different colours. Our estimates suggest that over 3.5 lakh car stickers have been sold so far," says Tejinder Pal Singh, a shopkeeper based in Jalandhar.

At the recent Holla Mohalla festival too, stalls stocked the paraphernalia in huge numbers, and these disappeared off the shelves.

Guarded in his response, Punjab DGP P S Gill says: "We are aware of this and are keeping a close watch."

Historian G S Dhillon attributes the fascination with the man blamed for the advent of terrorism in Punjab to the "lack of genuine heroes in Punjab today". He says the state has no charismatic and mass Sikh leader and youngsters who haven't seen the dark days of the 1980s are allured by a character whose reputation has been enhanced by myths and fake legends.

The unequivocal endorsement of Bhindranwale by the Sikh clergy may have also contributed to his popularity. Avtar Singh Makkar, president of the Shiromani Gurudwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), says: "For us he was a martyr. We have also installed his portrait in the Golden Temple museum."

Kanwar Pal Singh, Secretary, Political Affairs, of the Dal Khalsa, adds: "We buy these calendars and other memorablilia and distribute them free of cost to our members. Last year, which marked 25 years of the Operation Blue Star, we commemorated Bhindranwale's martyrdom."

Lords of Terror: The real-life Mogambos

When Mr. India (Anil Kapoor) did the vanishing act and destroyed adversary Mogambo in the 1980s blockbuster of the same name, the whole country sat up and shouted "India Khush Hua"! Twenty years down that road, India continues to fight a bunch of real life Mogambos who have inflicted a thousand cuts on our social fabric. Unfortunately, real life has not imitated reel life as we continue our wait for a Mr. India who can defeat these Lords of Terror.

What is even more embarrassing is that unlike Mogambo and his faceless bunch of villains, these modern day terror masterminds have a face that keeps popping up into our living rooms, courtesy the television screens. They are seen in cricket matches, political rallies, and via video tapes gleefully passed on to TV stations. Simply put, they are cooking a snook at India and sieve-like security system.

Here is a look at some of the names that have sent a chill up our collective spines and whose whereabouts are not as big a mystery some of us like to believe. We start off with a list that the government of India shared with Pakistan in 2002 and again in 2008 after the 26/11 carnage. We also proffer a gentle reminder to our readers that the two countries are engaging in a fresh round of talks in the near future. Will this list get shared again?

Marx on Religion

These two selections from Marx's writings are his clearest statements about religion. The first contains his famous (or infamous to some) "opiate" statement, but here presented in the total context in which he wrote it. The second selection contains his view of Atheism and an interesting statement about communism NOT being the final goal of human endeavors.

From...Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right

by Karl Marx

Appeared in the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbucher, February, 1844

(Color has been added for emphasis)

For Germany, the criticism of religion has been essentially completed, and the criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticism.

The profane existence of error is compromised as soon as its heavenly oratio pro aris et focis ["speech for the altars and hearths"] has been refuted. Man, who has found only the reflection of himself in the fantastic reality of heaven, where he sought a superman, will no longer feel disposed to find the mere appearance of himself, the non-man ["Unmensch"], where he seeks and must seek his true reality.

The foundation of irreligious criticism is: Man makes religion, religion does not make man.

Religion is, indeed, the self-consciousness and self-esteem of man who has either not yet won through to himself, or has already lost himself again. But, man is no abstract being squatting outside the world. Man is the world of man — state, society. This state and this society produce religion, which is an inverted consciousness of the world, because they are an inverted world. Religion is the general theory of this world, its encyclopaedic compendium, its logic in popular form, its spiritual point d'honneur, it enthusiasm, its moral sanction, its solemn complement, and its universal basis of consolation and justification. It is the fantastic realization of the human essence since the human essence has not acquired any true reality. The struggle against religion is, therefore, indirectly the struggle against that world whose spiritual aroma is religion.

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions.

The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.

Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers on the chain not in order that man shall continue to bear that chain without fantasy or consolation, but so that he shall throw off the chain and pluck the living flower. The criticism of religion disillusions man, so that he will think, act, and fashion his reality like a man who has discarded his illusions and regained his senses, so that he will move around himself as his own true Sun. Religion is only the illusory Sun which revolves around man as long as he does not revolve around himself.

It is, therefore, the task of history, once the other-world of truth has vanished, to establish the truth of this world. It is the immediate task of philosophy, which is in the service of history, to unmask self-estrangement in its unholy forms once the holy form of human self-estrangement has been unmasked.

Thus, the criticism of Heaven turns into the criticism of Earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law, and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics.

But since for socialist man the whole of what is called world history is nothing more than the creation of man through human labor, and the development of nature for man, he therefore has palpable and incontrovertible proof of his self-mediated birth, of his process of emergence. Since the essentiality [Wesenhaftigkeit] of man and nature, a man as the existence of nature for man and nature as the existence of man for man, has become practically and sensuously perceptible, the question of an alien being, being above nature and man -- a question which implies an admission of the unreality of nature and of man -- has become impossible in practice.

Atheism, which is a denial of this unreality, no longer has any meaning, for atheism is a negation of God, through which negation it asserts the existence of man. But socialism as such no longer needs such mediation. Its starting point is the theoretically and practically sensuous consciousness of man and of nature as essential beings. It is the positive self-consciousness of man, no longer mediated through the abolition of religion, just as real life is positive reality no longer mediated through the abolition of private property, through communism. Communism is the act of positing as the negation of the negation, and is therefore a real phase, necessary for the next period of historical development, in the emancipation and recovery of mankind. Communism is the necessary form and the dynamic principle of the immediate future, but communism is not as such the goal of human development -- the form of human society.

Taslima Nasrin: Woman in exile

Agent provocateur or a bold voice of dissent against patriarchy? Rubaiyat Hossain re-examines Bangladesh's most controversial author.

You gave me poison.

You gave me poison.

What shall I give you?

I'll give you my pitcher of water

Down to its last drop.

--Taslima Nasrin (In Return)

Taslima Nasrin is a forbidden name in Bangladesh. No one likes her. Even the women's rights activists and female writers shy away from her. The validity of her political position as a woman, and the craftsmanship of her literary work have been questioned widely.

I can understand the extreme resentment against her due to the strong oppositional position she has taken with regard to Islamic scriptures (or any religious scripture for that matter), but I keep thinking that there has to be something else in her writing, something else which has established her as an icon in the literary world.

The iconification of Taslima Nasrin is covered with a negative hue. Her sexuality is always brought into question, and she is constructed as a thoroughly immoral woman who is doing crazy things just to get public attention. However, this is a very generalized, partial, and simplified understanding of Taslima Nasrin as a writer.

When her recent book Dwikhondita (also known as Ka) came out I remember calling a book-store in New York in order to get a copy of the book.

The store owner told me enthusiastically: "In this book, Taslima has named all the writers she has slept with."

When I got the book and read it thoroughly, I was surprised when I reflected on the store owner's comment, since the book came across to me as nothing more than a very well-written emotional biography of a female writer trying to make it in a literary world mostly

dominated by males.

The book reveals Taslima's experiences of sexual abuse, and uncovers her relationships with prominent writers. It is the most accomplished of her literary pieces, but it still failed to draw any criticism based on literary lines. Almost all discussions of the book revolved around scandals, and Taslima's immorality as a woman.

The wider level of reaction towards the book reveals the patriarchal double standards that reign over the culture of Bangla literature. It is very common for male writers to write about sexuality, in fact Sunil Gangopadhay's famous biographical travelogue, Chobir Deshey Kobitar Deshey, openly discusses his sexual experiences in the United States and Europe. Gangopadhay's biography does not bring into question his moral integrity because male writers are not only sanctioned to talk about sexuality, but writers like Sunil Gangopadhay, Shomoresh Boshu, and Buddhadev Bosu are acclaimed for talking openly about sexual experiences, thus ushering in a new state of modernity in Bangla literature.

I want to argue that Taslima Nasrin is condemned, especially in the literary circle, because she is the first woman to talk openly about female sexuality in Bangla literature. She is also the first one to write openly about her sexual encounters with other writers (may they be true or fabricated). Whether Taslima's accounts in Dwikhondita were based on reality is an entirely separate debate, but from the ill reaction towards the book, we come to understand once again that when a female talks openly about her sexuality it is not well received.

I want to argue that Taslima Nasrin is condemned, especially in the literary circle, because she is the first woman to talk openly about female sexuality in Bangla literature. She is also the first one to write openly about her sexual encounters with other writers (may they be true or fabricated). Whether Taslima's accounts in Dwikhondita were based on reality is an entirely separate debate, but from the ill reaction towards the book, we come to understand once again that when a female talks openly about her sexuality it is not well received.

It strikes me as a strange phenomenon, since most of Bangla literature, even pieces by Kalidasa, use women's bodies and sexuality as a prominent theme of rasa. The social approval for male writers to write about female bodies, and the imposed silence on women writing about their own bodies highlight the overall contour of Bangla literature where women are officially denied access to conceptualize, and write about, their own sexuality.

When a woman writes, it is essentially different from a man writing, because women's personal experiences have a political implication. Women's personal experiences reveal the division, and implementation of patriarchal power through women's intimate experiences of sexual objectification.

For example, the recent publication of Sylvia Plath's unabridged journals and unrevised version of her book of poems Ariel, with a forward by her daughter Frieda, informs us of Plath's extreme marginalization as a female poet, and her intimate experiences of sexual objectification in her marriage with poet Ted Hughes.

Plath's work makes so much more sense when she is contextualized as a female poet fighting against the odds of 1950s patriarchal culture of the US and the UK. Virginia Woolf has pointed out that intellectual freedom depends on material things, and it informs women's psychological lives and their creative outcome.

Esther, the protagonist of Sylvia Plath's novel The Bell Jar, sits down in front of her type-writer to write a novel and realizes that she cannot write, simply because she has "no experience." Domestic isolation, narrow social exposure, lack of access to material things to own a "room of their own" restrict women from writing about their unique experiences of objectification and marginalization.

Woolf has also pointed out that telling the truth about one's experience as a body means "rejecting the ideal, pure image of woman." That is exactly what Taslima Nasrin has attempted to do in her literary work.

Nasrin has flipped the use of womb from a place of reproduction to a place of resistance. The main protagonist of her novel Shodh uses her womb to give birth to an illegitimate child in order to take revenge on her husband. Whether or not this form of rebellion is desirable, or even empowering, is a separate debate. What I want to draw readers' attention to is Nasrin's alternative use of the female body, not only as a passive object, but as an active agent resisting an oppressive cultural code that masters women's bodies and reproductive organs.

When Nasrin described a rape scene in Nimontron, many people found it to be completely obscene. In fact when I read it as a school-girl I thought it was a little too much, but now that I reflect back upon the book as a graduate student, I can finally find some relevance in actually spelling out the totally obscene, violent, and perverted lust that is being played out on women's bodies everyday. After all, why do we feel so uncomfortable reading a female writer writing about rape, when we are totally comfortable reading the newspaper reports on rape, mostly written by male reporters, which are sometimes not very far from being pornographic.

When Nasrin described a rape scene in Nimontron, many people found it to be completely obscene. In fact when I read it as a school-girl I thought it was a little too much, but now that I reflect back upon the book as a graduate student, I can finally find some relevance in actually spelling out the totally obscene, violent, and perverted lust that is being played out on women's bodies everyday. After all, why do we feel so uncomfortable reading a female writer writing about rape, when we are totally comfortable reading the newspaper reports on rape, mostly written by male reporters, which are sometimes not very far from being pornographic.

It is a pity that men and women have shied away from benefiting from Nasrin's keen and sharp analysis of gender and power dynamics of women's sexual objectification.

Her literary work creates a rupture in the episteme of patriarchal power-knowledge nexus, and opens up a space for the expression of female individuali but we have failed to take advantage of that space because the patriarchal media and literary circle have scandalized Taslima Nasrin to an extent that we do not even stop give her a second thought.

We fail to acknowledge that Taslima Nasrin is actually a pretty good writer, and, in fact, she is the first one to openly speak up about issues of sexuality ranging from menstruation, sexual harassment, rape, masturbation, etc. It is not uncommon to read passages in Bangla literature about male masturbation, in fact a great literary link is established between the male sexual organ and his poetic exploration of imagery and emotions.

Males are given the social approval to openly explore their sexuality and establish a link between their sexual experiences and the conceptualization of the world around them.

Females, however, are totally condemned for writing about their own sexuality, which is symptomatic of the fact that society wipes out all agency from the hands of women in controlling their own sexuality, and puts it in the hands of the males. In order to claim one's space in society as a free agent, one must, primarily claim rights over one's own body.

The NGO movements attempting to stop dowry, polygamy, or child-marriage do not cause a big stir in our social fabric, because those movements do not reach into the depths of patriarchal value and power system.

Taslima, however, by claiming rights over her own body and sexuality, has shaken the core of our patriarchal value system. She has stepped out, and declared that she is not afraid to be called "fallen," because to be emancipated as a woman means in many ways to be recognized as "fallen" in our societal system.

Rubaiyat Hossain is an independent film-maker and Lecturer at Brac University.

Constructing Outraged Communities and State Responses:

The Taslima Nasreen Saga in 1994 and 2007

Abstract

Taslima Nasreen, the exiled Bangladeshi author, was forced to leave India, her adopted homeland, in March 2008 after being under 'security protection' for months following street agitation against her writings in Kolkata. The events between August 2007, when she was physically attacked in Hyderabad, and March 2008, when she left the country, were reminiscent of those in Bangladesh in 1994 which led to her departure from there. In both instances, the states' responses were her forced removal from the country to placate the agitators. In this paper I analyze the events on the ground and the responses of the states. I argue that these events demonstrate how 'outraged communities' are constructed, and symbols are invented to mobilize the community. The role of state has received little attention in the extant discussions while I contend that states bear a significant responsibility in engendering the controversy.

Index terms

Keywords :

Bangladesh, Taslima Nasreen, India, Outraged Community, Religion, Islamist, Symbol, Emotion, OtherPlan

Top of pageFull text

'I do not want any more twists to my tale of woes. Please do not give political colour (sic) to my plight. I do not want to be a victim of politics. And I do not want anybody to do politics with me.'

Taslima Nasreen, Hindustan Times, November 27, 2007

- 1 Nasreen has since been allowed to return to India. On her return to New Delhi on 8th August 2008,(...)

1Taslima Nasreen, the exiled Bangladeshi author, once again attracted the attention of the international media as a result of events in India beginning in August 2007. The physical attack on her at a book launch in Hyderabad was followed by riots in Kolkata, the capital of the state of West Bengal, in November 2007. Nasreen was then forced by the government to leave the city she called her second home and was shunted from one city to another. She was kept under security protection for months in undisclosed locations. Finally, in mid-March 2008, after 110 days in the 'safe custody' of the Indian government Nasreen left India for Europe1.

2These events were reminiscent of the events of 1994 which led to her exile from Bangladesh. At that time, she not only became the target of the 'religious zealots' who demanded that she be killed for heresy but was also charged with blasphemy in a court. After 44 days of hiding she was given a 'safe passage', thanks to the intervention of the international community. Her detractors claimed that she had offended the religious sensitivities of the Muslim 'community'. In 2007, the organization of the attack and the agitation was claimed by Indian 'Muslim groups' which insist that one volume of her autobiography (published 4 years ago) and her other writings have offended their religious sentiments.

3The uncanny similarities of these two series of events and the responses of the authorities in Bangladesh and India deserve close scrutiny at various levels. Interestingly, these events (i.e., the 1994 agitation in Bangladesh and the 2007 violence in Kolkata), took place in the background when other outraged communities, based on larger political demands, were in the making.

4In this paper I analyze the events on the ground and the responses of the states. I argue that these events demonstrate how 'outraged communities' are constructed, and symbols are invented to mobilize the community. These events also demonstrate, among other issues, how states in South Asia, particularly Bangladesh and India, deal with 'outraged communities'; and what, if any, role states play in the construction of the outraged community. The paper's focus on the 'state response' is not to suggest the primacy of the state in these issues; instead the dynamics within the groups of non-state actors and how the outrage is framed are important in understanding the trajectories of the events. But the state's role has received little attention in the extant discussions while I contend that states bear a significant responsibility in engendering the controversy. The banning of the book is a case in point. In Bangladesh Nasreen's book Lajja (Shame) was proscribed in mid-1993 before the agitations against the author ensued; similarly, in West Bengal, her book Dwikhondito (Split in Halves) was banned in 2004, three years before the street agitations gripped the state capital Kolkata. The paper, therefore, intends to address the absence of the discussions on states' roles.

5Four sections follow this introduction; the events of 1997 and 2007-08 are described in the first and the second sections. The third section presents the analysis drawing on both events and their significance in understanding the complexity of the politics of emotion. Concluding thoughts comprise the final section.

Episode 1: Bangladesh, 1994

6The sixty-day episode of turmoil and mayhem and the eventual exile of Taslima Nasreen from Bangladesh took place between 4th June and 4th August 1994, but this was in the making from the beginning of 1993. An author, a columnist and a medical doctor by profession, Nasreen was known only to the middle class literate population until the government confiscated her passport on 23rd January 1993 allegedly for traveling under a 'false identity'. Although providing a false identity is a misdemeanor according to the laws of Bangladesh, and as a public official she could have been subjected to administrative disciplinary measures, the government took no further action against her. This, however, was not an indication of leniency towards Nasreen, but the usual bureaucratic way of dealing with such issues in Bangladesh; that is to do something without getting too involved in 'trifling matters'. The government's action was caused in part by Nasreen's high-profile trips to India since she had won a coveted literary prize in Kolkata the previous year. The government headed by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which champions anti-India feelings, was also trying to send a signal that it was not thrilled to see such intimacy with the West Bengal literary community2.

- 2 In mid-1993, a government official commented to the author in a personal conversation that if Nasr(...)

7By the middle of the year, there was a conspicuous change in the attitude of the government: on 10th July 1993 Nasreen's novel Lajja (Shame) was proscribed. The book, published in February 1993, became an instant best-seller and by July more than sixty thousand copies had been sold, a major success by Bangladeshi standards. The book, depicting the agony of a Hindu family during the communal riots in Bangladesh after the demolition of the Babri Mosque (6th December 1992) in India, stirred debate among Bangladeshi intellectuals; but nobody expected the book to be banned, because there were no precedents to draw upon in regard to fictional works. The government action came on the heels of a move by a small religious group from the northeastern town of Sylhet.

8The previously unknown 'religious' group named Shahaba Sainik Parishad (later discovered to have a large following and suspected of connections with a group in Pakistan) from Sylhet – a city northeast of Dhaka – issued a fatwa sentencing her to death and placing a reward of taka 50,000 (approximately US$1,250) on her head on 23rd September 1993. The group retracted its statement after severe criticism from various sectors of society. However, it continued to demand the banning of all her books and that she be put on trial on charges of 'blasphemy'. Two cases were lodged in the local courts of a northeastern city by two individuals, presumably members of the aforementioned group, alleging that Nasreen's writings had offended their religious sentiments. After a preliminary hearing in which Nasreen was represented by her attorney, these cases were shelved. Nasreen also filed a suit against one Maulana Habibur Rahman and six others who were leading the campaign against her. Nasreen complained that they incited people in a public meeting in Sylhet against her, that a death threat had been made in the said meeting, and that she was at risk because of the threat.

9While a pseudo court battle was going on in Sylhet, the group that called for the banning of Nasreen's books continued its agitation and organized several demonstrations – initially outside Dhaka, but later in the capital. In November, the group called a general strike in Sylhet. Shahaba Sainik Parishad's (SSP) demonstrations began to draw a large crowd. Most of the participants, according to eyewitness accounts, were students of madrassahs and activists of religiopolitical parties, including the Jamaat-i-Islami [JI]. The JI initially claimed that it had no hand in this fatwa, but gradually it became clear that the demonstrations were manned by JI activists as the SSP had little or no support and little organizational capacity to mobilize the masses.

10After declaring a bounty on her head militants intensified their campaign against Nasreen. She herself 'appealed via fax and phone to the Western media and human rights groups' (Wright 1995: 4) to put pressure on the government to ensure her safety. Consequently, a number of international human rights groups asked the Bangladesh government to guarantee her safety, and international writers' associations began to unfurl their flags in support of Nasreen.

11The situation took a dramatic turn at the beginning of June 1994. In May, soon after receiving a new passport, Nasreen left for Paris. On her way back from Paris, she visited Kolkata and was interviewed by the Indian English-language daily the Statesman. In her 9th May 1994 interview, she reportedly said that the Quran was written by a human being. Nasreen, according to the report, also said that she was against any partial changes in the Quran, implying that she wanted a total revision of the Quran. In a rejoinder published on 11th May 1994, Nasreen denied that she made any such remarks.

12Both the interview and the rejoinder remained unknown to Bangladeshi readers until a government-owned English daily in Dhaka reprinted the interview in early June, without the necessary permission from the Statesman and without Nasreen's rejoinder. The reason the story was reprinted became obvious within a week. The government lodged a case against her under Section 295A of the Penal Code, which stipulates that a person must serve two years in jail for offending religious sentiments. The court issued a warrant for Nasreen's arrest on 4th June 1994. She then went into hiding.

- 3 For details of the events see the fourth part of Taslima Nasreen's autobiography Sei Sob Andhokar((...)

13Meanwhile, some thirteen Islamist parties, factions, and organizations formed an alliance to put pressure on the government to arrest Nasreen, waged a campaign against almost all secular intellectuals, attacked the offices of newspapers that showed even the slightest sympathy for Nasreen or had criticized religious groups on previous occasions, and ransacked bookstores selling Nasreen's books3.

14Behind the scenes, negotiations took place in New York between Bangladeshi authorities and PEN's Women Writers' Committee, which pressured the Bangladesh government to allow Nasreen to leave the country. Finally, a face-saving formula was worked out. After receiving assurances that she would not be incarcerated, Nasreen surrendered to the court on 3rd August 1994, represented by a pool of qualified lawyers, including a former foreign minister. The court granted bail. Within a week, she left for Sweden 'on an invitation from a Swedish writers association'.

15The above narrative of the events on the ground, especially the street agitation provides an impression that the government was responding to the demands of the outraged community/groups hurt by Nasreen's comments. But it also raises questions as to why the 'outrage' was expressed at that time, especially involving a book published more than a year before. Equally important is the question: were the street mobilizations spontaneous? Anyone familiar with Bangladeshi politics and those who observed the demonstrations would respond negatively. Evidently, organized political forces, Islamists of various shades to be precise, with a specific agenda were at the forefront of these agitations. The prevailing impasse in domestic politics and different hidden agendas of the political actors of Bangladesh created the imbroglio. Before going into details, let me point out once again that Nasreen's interview, which served as a stirring prelude to a drama that lasted for exactly sixty days, was published on 9th May but remained unknown to Bangladeshis until a government-owned newspaper reprinted and highlighted it. There are reasons to suspect that it was reprinted only to create an environment conducive to filing a case against her.

16In May 1994, four features of Bangladesh politics stood out: first, the opposition political parties, which had been boycotting the Parliament for more than two months, demonstrated their firm determination not to return to the house; second, and a corollary to the first feature, it was becoming increasingly obvious that the relationship between the Jamaat-i-Islami and the ruling BNP had become strained, and consequently a new long-term alliance between the Awami League (AL) and the Jamaat-i-Islami was in the offing; third, a verdict was forthcoming on the eighteen-month-long troubled citizenship trial of Golam Azam, the ameer (chief) of the Jamaat; and fourth, the Jamaat was looking for an opportunity to bring its proposed blasphemy law into public discussion. Interestingly, none of this was happy news for the ruling party, and all of it involved the Jamaat-i-Islami.

17On 1st March 1994, opposition political parties led by the Awami League began to agitate for a constitutional amendment that would allow the holding of future elections under a caretaker government instead of under the ruling government. In a not-so-surprising move, the Awami League formed an alliance with the Jamaat-i-Islami, an old-time friend of the ruling party. The opposition's boycott of Parliament began like a usual walkout, but soon it became clear that the opposition was trying to hold on to its demand to amend the constitution to hold all future elections under a nonpartisan caretaker government. The opposition threatened that it would continue to boycott parliamentary sessions unless the ruling party bowed to its demand. Opposition parties engaged in a series of agitation programs. Although the public at large was in a state of confusion with regard to the demand raised by the opposition parties, the immediate reaction of the press was in favor of the demand, which the ruling party mistook for popular support. But the confrontational mood of the opposition was not welcomed by a large section of the population, especially the business community. The ruling party's initial posture was to disregard the issue altogether. But by May 1994 the BNP became visibly frightened as its support fell rapidly. What concerned the ruling party most was the emerging alliance between the Awami League and the Jamaat-i-Islami. The former had always been a rival of the ruling party, but the latter provided support for the ruling party whenever it was necessary. In fact, the BNP had come to power with the help of the Jamaat, whose twenty MPs extended their whole-hearted support to the BNP in forming the government in 1991. Ostensibly, Jamaat was now deserting the BNP.

18For the BNP, this situation called for immediate action to diffuse the brewing tension and reestablish the old order. For the ruling party, two goals had to be achieved: first, to divert public attention from the opposition's demand; second, to create a division within the emerging alliance. Nasreen's interview provided the ruling party with an issue that had the potential to help achieve both these goals. An issue pertaining to religion was sensitive enough to arouse concern, while at the same time, members of the emerging alliance – because of their different ideological orientations – were destined to take different stands, rendering the alliance practically ineffective. Both politics and tricks played their roles. The ruling party's strategy to divide the opposition alliance did not work as well as expected. Contrary to the expectation of the BNP and the general masses, the Awami League distanced itself from the issue, allowing the Jamaat to run the show. The Awami League was more interested in pursuing a closer relationship with the Jamaat than with fighting a battle for a secularist cause. In the name of a combined parliamentary opposition, the AL was working with the Jamaat and intended to intensify the street agitation programs. The Jamaat, at an early stage of the crisis, kept a low profile. But perhaps because of the Awami League's inaction, the Jamaat soon joined the anti-Nasreen agitation. Therefore, the split that the ruling party expected did not materialize. The Islamists outside the ambit of the Jamaat-i-Islami, especially the militant organizations, soon forged an alliance called Sammilita Sangram Parishad (Alliance for United Movement).

- 4 In 1971, Golam Azam, then chief of the East Pakistan wing of the Jamaat-i-Islami, actively collabo(...)

19The Jamaat had two agendas: firstly, to divert public attention from the citizenship trial of Golam Azam4; and secondly, to highlight the proposed 'Blasphemy law'.

20The hearing concerning Golam Azam's case in the Supreme Court began on 4th May 1994, and from the beginning it was evident that the process would not take a long time, meaning a verdict might be forthcoming. In the meantime, the anti-Azam movement turned into a movement against those who had actively collaborated with the occupation regime in 1971. The organizers set up a Public Inquiry Commission to collect evidence against a number of collaborators, most of whom were the current leaders of the Jamaat. The initial enthusiasm and fervor of the movement subsided, but it did not lose all its steam. It was expected that a verdict in favor of Azam might steer the movement to a new phase. Hence the Jamaat wanted to create a situation in which the issue of Golam Azam would become of secondary in importance and the movement against him would face an uphill battle to prove its worth. Their hopes came to fruition when the Supreme Court delivered its judgment on 22nd June 1994, in favor of restoring Golam Azam's citizenship as a Bangladeshi.

21The restoration of Golam Azam's citizenship through a court verdict frustrated the opponents, but gave Jamaat the opportunity it was looking for to bring a specific issue to the fore: the proposed blasphemy law. The bill was proposed in 1992 and tabled in 1993, but discussion continued within the confines of the Parliament building. In 1994, owing to the fact that the opposition members of the Parliament were engaged in a boycott, the Jamaat aimed to bring up the issue through some other means.

22Nasreen's comments in the Indian newspaper the Statesman on 9th May provided the Jamaat with the opportunity it was looking for. As soon as her comments were made known, Islamists in general and the Jamaat in particular argued that the article proved the need for a blasphemy law. The statement issued by some 101 pro-Jamaat intellectuals on 1st June; the statement of Matiur Rahman Nizami, the secretary general of the Jamaat-i-Islami, on the Nasreen issue on 8th June; and numerous articles in the daily Inquilab and the daily Sangram, both mouthpieces of the Islamists, insisted that the situation would not have arisen if there had been a blasphemy law. Other newspapers joined the fray (e.g, New Nation 1994: 5)

- 5 Bangladesh and India both inherited a colonial law in regard to the acts of blasphemy. The Penal c(...)

23The JI had attempted to table a Blasphemy Law, akin to the law passed and implemented in Pakistan, in 1992, but had not succeeded5. Learning from their limited success in 1992, the Islamists, and the Jamaat in particular, did not rely on one single case to prove their point. Instead, to intensify their campaign, they also targeted a Bengali daily, the Janakantha, which since the beginning of the year had relentlessly tried to expose the persons involved in and the factors behind the ubiquitous rise of fatwabaz (those who decree an edict) in the country. In an editorial in the 12th May 1994, issue, the Janakantha showed how orthodox and illiterate mullahs were misinterpreting the Quran and the Hadith. The Islamists alleged that this specific article had offended the religious sentiments of the Muslim community and called upon the government to bring charges against its editor. The government picked up the issue and filed a case against the editor (Atiqullah Khan Masud), the advisory editor (Toab Khan), the executive editor (Borhan Ahmed), and an assistant editor (Shamsuddin Ahmed) of the newspaper under Section 295A of the Penal Code.

- 6 Taslima Nasreen made a brief visit to Bangladesh in September 1998 to see her terminally ill mothe(...)

24It was the first time since independence that a newspaper had been charged under this clause. Ironically, during the twenty-four years of Pakistani rule, when the cry of 'Islam in danger' was all too familiar, no newspaper had ever faced a charge under this clause; but it happened in Bangladesh, which had once proclaimed secularism as its guiding state principle. Both the advisory editor and the executive editor were arrested on 8th June 1994. They appeared before the court on the same afternoon, and their bail petition was denied. Accordingly, they were sent to jail. The assistant editor surrendered to the court later and faced the same fate. Eight days later, Masud was granted bail by the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court. Borhan Ahmed and Toab Khan were granted bail on 15th and 20th June, respectively (Ahmed 1995). But all of this was overshadowed by the Nasreen saga and received little attention outside Bangladesh. Bangladeshi secularists, unfortunately, failed to highlight the issue altogether. The street agitation continued until she left the country in August6. The state machinery not only allowed these violent demonstrations to continue and death threats to be waged against the author, but also prioritized the issue of dealing with the offenses related to hurting religious sentiments over the demand for trials of Golam Azam and others for their involvements in war crimes.

25Thus, the first grassroots movement against the Islamists, particularly the Jamaat-i-Islami, since their resurgence in 1979 was dissipated - not by clamping down on the movement but through constructing a diversion and by cultivating an outraged community.

Episode 2: India, 2007

26The heightened media coverage of the second episode of the Nasreen saga began with the attack on her at Hyderabad on 9th August 2007. During a book launch at the city's press club Nasreen was attacked by 'an unruly crowd' (NDTV 2007) under the leadership of three state assembly members of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (MIM). The party chief extended his wholehearted support to the attack and threatened to kill Nasreen himself (IANS 2007). A small local group, named Dasgah-e-Jehad-Shaheed, claiming itself the representative of the Muslim community, held a demonstration in Hyderabad on 11th August where it demanded that the author be expelled from India. By then Nasreen returned to Kolkata where she had been living for almost 3 years. The Imam of a local mosque, Syed Noor-ur-Rahman Barkati, issued a death threat against Nasreen on 17th August: 'Anybody eliminating her would be given Rs 100,000 and unlimited rewards if she does not leave the country immediately. She has insulted Islam and continued to create problem in this country' Maulana Barkati told reporters (WebIndia123 2007; Hindustan Times 2007).

- 7 The most obvious indication of the state government's inclination towards removing her from the st(...)

27After more than three months of calm, the issue re-emerged in violent form on the streets of Kolkata on 21st November 2007: the All-India Minority Forum's demonstration demanding that Taslima Nasreen's Indian visa be revoked and that she be forced to leave the country turned into a city-wide riot (BBCNews 2007). The scale of violence, not seen in Kolkata for decades, gripped the city for a day. The West Bengal government immediately put pressure on her to leave the state7, within hours she was forced by law enforcing agencies to move to Jaipur. She was then thrown out of the state of Maharashtra towards Delhi, where she was put in an undisclosed safe house under the supervision of the central government. The cabinet ministers of the central government allegedly pressured her to make a public apology. The Foreign Minister commented that India would continue to provide her 'shelter' as a guest but she would have to show restraint. Pranab Mukherjee told the Indian Parliament on 28th November 2007, that 'It is also expected that the guests will refrain from activities and expressions that may hurt the sentiments of our people' (AOL News 2007).

28On the same day, Taslima Nasreen informed her publisher in Kolkata to delete sections of the second part of her autobiography published in 2002. Announcing her decision Nasreen told the press, 'I have withdrawn some parts of my book Dwikhondito. Some said parts of the book were hurting the sentiments of the people. I hope after its withdrawal, there would be no more controversies. … The decision to withdraw these parts from Dwikhondito is to prove that I never wanted to hurt the people's sentiments. I hope now I will be able to live peacefully in India and Kolkata' (Hindustan Times 2007). Ironically, after a court victory over the same book Nasreen commented, 'If they had asked me to change or delete even one word as a precondition to lifting the ban, I would've gone to the Supreme Court. To me, changing two pages and changing one word is one and the same thing' (Telegraph 2007).

29Despite this concession and publicly giving in to the demands of the demonstrators, Nasreen was not allowed to stay in India, let alone return to Kolkata. She remained incommunicado until her departure in late-March 2008 when her second exile began.

30In India, particularly in West Bengal, Nasreen was hounded in 2000, 2004 and 2006 and fatwas were issued against her. Yet the government did not intervene to prevent the recurrence of such events or to 'appease' those who claimed that they were speaking on behalf of the Muslim community. For example, in March 2000 an organization named the Reza Academy of Mumbai threatened that if she ever set foot there she would be burned alive (Times of India 2007). In January 2004, Syed Noor-ur-Rahman Barkati of Tipu Sultan mosque in Kolkata denounced the author in his Friday sermon, commented that 'Her face can be blackened with ink, paint or tar. Or she can be garlanded with shoes.' Maulana Rahman also offered a reward of 20,000 rupees (about US$500) to anyone who would carry out the act. In June 2006, Maulana Barkati issued what he described as a 'fatwa', after Nasreen's speech at a conference in Kolkata. Maulana Barkati said to a local TV channel: 'I've issued a fatwa against her. After the Jumma namaz [Friday prayers], I said if anyone blackens her face and drives her out of India, I will give him 50,000 rupees.' He later retracted and insisted that a fatwa cannot be issued verbally.

31What prompted the decisive step of the West Bengal government in 2007 to address the issue raised by the 'outraged' Muslim community? The answer to this question is not only important in understanding the government's actions but also to highlight the similarity between the events in 1994 and 2007.

32Like with the situation in Bangladesh in 1994 we need to delve deep into other events connected to the larger political scene of West Bengal politics to find an explanation for the actions. In a textbook copy of the incident in Bangladesh, the West Bengal government first banned her book, Dwikhondito (Split in Halves) in 2004 and thus created an environment to move against her should that become necessary. The ban was later rescinded by the Indian court.

33The 2007 episode, on the part of the agitators, began in March when Taqi Raza Khan of the All India Ibtehad Council, issued a fatwa against Taslima, threatening to kill her. Khan offered an inducement of 500,000 rupees ($11,760) for anyone who would behead ('sar qalam karna') the author. He claimed that he had the full support of the All-India Muslim Personal Law Board (Khaleej Times 2007). The fatwa was condemned by many Muslim representatives, for example, Safia Naseem, member of the All India Muslim Personal Law Board, Maulana Naimur Rehman, general secretary of the Ulema Council, and Yasef Abbas, general secretary of the All India Shia Personal Law Board to name but a few (Times of India 2007a). Detractors of Nasreen were looking for an opportunity to highlight their demand and thrust themselves onto the national scene. But the opportunity emerged because of an entirely different and unrelated set of events: the growing resistance to the government's plan to set up a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) allowing a foreign company to build a factory in Nandigram causing the eviction of thousands of hundred of local residents, who happened to be Muslims, and the mysterious death of a Muslim youth named Rezwanur Rahman allegedly with the connivance of the Kolkata police.

34The Nandigram issue had been brewing since January 2007 when the local authority (i.e., the Block Development Office, BDO) announced the seizure of land. Protests and clashes between police and local residents ensued. As the local administration failed to implement the plan, the state government viewed this as a law and order situation and consequently decided on 9th March that it would resort to police action. The local members of the ruling CPIM were also included in the force sent to 'retake' the villages. The police action on 14th March caused the deaths of local people, incidents of rape, and complete mayhem. However, the local resistance continued and the police actions, particularly their heavy-handedness, attracted national and international media attention. In the following months, anti-government political forces, especially the Trinamul Congress led by Mamata Banerjee, became involved and were effectively trying to cash in on the situation. But the mobilization remained, in large measure, local initiatives. The Kolkata-based civil society was divided on the issue and very slow in responding to the on-going locally-inspired resistance to the government industrial development plan. Between March and November, low-level conflict continued; the residents returned to their homes, the movement gathered momentum, and the government was increasingly becoming impatient. Finally, on 8th November, the government forcibly retook the villages. The result was less bloody than the March events, but no less disheartening. As for the local people, they were evicted from their homes, anyway. These events galvanized a section of the civil society leading to a massive protest in Kolkata on 14th November 2007. In the words of Sumit Chowdhury, this was a reflection of the 're-awakened conscience'. Chowdhury states that 'overnight, various platforms sprouted, all of which took place without a political party or bloc lending a hand, and unsupported by any political ideology. This citizens' uprising appeared spontaneous, bypassing the winding alleys of party politics' (Chowdhury 2008, § 2)