I have seen all the DEVAs and Devils and now watch them to align with the Zionist Nuclear Global Post Modern Order of Mass Detruction!

India clears policy to build new industrial zones

Union cabinet approves national manufacturing policy

Federal cabinet approves Rs 30 bn equity infusion in NABARD

RBI deregulates savings deposit rate; cost of funds to rise

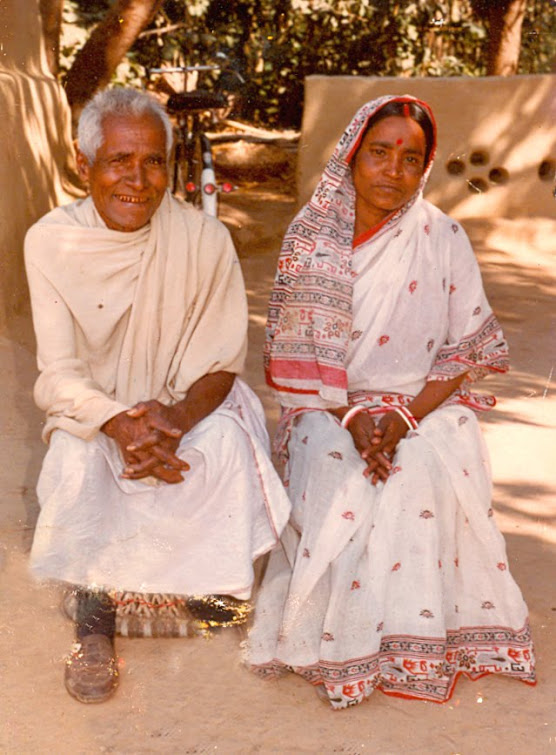

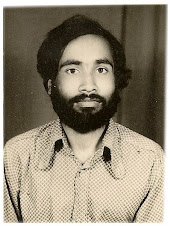

Indian Holocaust My Father`s Life and Time - SEVEN HUNDRED FIFTY

Palash Biswas

http://indianholocaustmyfatherslifeandtime.blogspot.com/

http://basantipurtimes.blogspot.com/

Now Mines are to be PRIVATISED! Mining Amendment was Passed with this agenda. Profit sharing is an Eyewashing only! Health and Education and Energy services have been already been Privatised! Indian Sky is Open to Foreign AIRLINES. PSUs are Being DIVESTED! Natural Resources have to be Sold Out to Foreign Capital! We would see, Water also be PRIVATISED very soon. Like Electricity, Seeds and Fertiliser, Indian Peasants have to Pay for IRRIGATION. And No Resistance at all! No Occupy Wall Street! We ahve an ANNA Team Off Course for Corporate Lobbying!

I have seen all the DEVAs and Devils and now watch them to align with the Zionist Nuclear Global Post Modern Order of Mass Detruction!

I have worked in the Jharkhand Coal Fields for Four Years since 1980 as a Professional Journalist. I invetigated Illegal Mining and Mines Accident. I was involved in Jharkhand Movement and had been linked to leaders like Comrade AK Roy, Vinod Bihari Mahato, Shibu Soren and the the team! I had watched Cooliery Kamgar Union and witnessed MIFIA WAR Live.

For last Three decades , I have been visiting the Aborigine Indigenous Huamnscape and have seen the EXCLUSION, Displacement, Ethnic Cleaning and REPRESSION all on the name od DEVELOPMENT, Law and Order, Democracy and development! Since 1991 , i have watched how MNCs and Corpoarte India have taken over Centarl India and Naturally Abundant Tribal Regions all over the Country!

Brahaminical Media, Intelligentsia, Civil Society, NGOs and the Political parties Push Hard on Divestment and Privatisation, Infrastructure and Development! On whose Cost? They have accomplished COMPLETE Mind Control as no less than the Illuminati Families Rockfeller and Rothschild have created an excellent Networtk in India!

Mining Legislation | |

|

Coal Minister Sriprakash Jaiswal and Coal India Chairman N C Jha had met early this month to review the company's performance in the first half of the current fiscal.

Th PSU, which accounts for 80 per cent of the domestic coal production had missed its half yearly target by about 20 million tonnes (MT) due to heavy rainfall in August and September and just achieved an output of about 176 MT against the target of 196 MT.

Jaiswal who met the representatives of Coal Mines Officers Association of India ( CMOI) here today appealed to them to work hard to make up for the public sector firm's production loss, an official statement said.

For the current fiscal the target of CIL is 452 MT. Earlier, CIL had asked the government to scale down its production target for the 2011-12 financial year to 448 million tonnes (MT) from 452 MT at present, fearing it will not be able to make up for slippage in output in the first half of the fiscal.

CIL had missed its production target last fiscal recording an output of 431 MT against the revised target of 440 MT.

-

Disinvestment target may be missed: RBI

mydigitalfc.com - 23 hours ago

By Falaknaaz Syed Oct 24 2011 The government may miss disinvestment target of Rs ... said the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in its Macroeconomic and Monetary ...Govt may miss revenue, disinvestment targets in FY11-12: RBI Moneylife Personal Finance site and magazine

Govt may miss revenue, disinvestment targets in FY'12: RBI IBNLive.com

all 4 news articles »

-

Plan A alive and kicking

Business Standard - Sundaresha Subramanian - 22 hours ago

But the government's Plan 'A' — disinvestmentthrough public offers or ... Coal India Ltd. Even after that, at Rs 22762 crore, divestmentproceeds fell well ...Plan 'A' alive and kicking Rediff

all 3 news articles »

-

Not aware of govt selling stakes in private companies...

Economic Times - 1 day ago

ET Now: The Finance Minister is confident that for this year Government of India will be able to reach the disinvestmenttarget of 40000 crore. ...India Official: Public Share Sales Not Enough to Meet ... Wall Street Journal

all 2 news articles » -

Oil India on disinvestment radar of the govt

NDTV.com - Raj Kumar Sahu - 5 days ago

NDTV has learnt that oil explorer Oil India could be on the disinvestment radar. Talks for furtherdisinvestment of OIL India are at a preliminary stage and ...SAIL divestment hits hurdle Business Standard

SAIL, Hindustan Copper drop FPO plansMoneycontrol.com

SAIL, Hind Copper drop FPO plans Hindu Business Line

Times of India - mydigitalfc.com

all 48 news articles » NSE:HINDCOPPER -BOM:513599 - BOM:500113

NSE:HINDCOPPER -BOM:513599 - BOM:500113

-

Indian Government looking for Exit route for Axis Bank, L&T and ITC

News Tonight - Monica Anand - 1 day ago

Indian government is looking to sell its stake in Axis Bank, L&T and ITC as ... requirements of the government and not much of progress ondivestment front, ...Govt eyes stake sale in ITC, Axis Bank, L TMoneycontrol.com

Govt eyes stake sale in L&T, ITC, Axis Times of India

all 5 news articles » BOM:532215 -NSE:AXISBANK - BOM:500510

BOM:532215 -NSE:AXISBANK - BOM:500510

-

RBI faces a conflict of choice

Calcutta Telegraph - 19 hours ago

Mumbai, Oct. 24: The Reserve Bank of India(RBI) today said it feared growth ... "There is a possibility of the central government missing itsdivestment ...Rate hikes may be over, but money will be costly till mid-2012 Firstpost

RBI may hike rates again; projects lower GDP, high inflation IBNLive.com

rbi s diwali gift repo rate raised by 0 25 pointsSamayLive

all 752 news articles » PINK:CBSU

PINK:CBSU

-

After bharatmatrimony.com, Yahoo to exit Tyroo, Callezee

Times of India - 4 days ago

The company's board, as part of a global clean-up plan, cleared the divestment in India three weeks ago. Yahoo had invested in these three firms between ... YHOO - TYO:4689

YHOO - TYO:4689 -

No disinvestment of Air India: Vayalar Ravi

Times of India - 5 days ago

PTI | Oct 20, 2011, 03.59PM IST NEW DELHI: Government on Thursday ruled outdisinvestment of Air India saying it is trying to bring the cash strapped ...No disinvestment of Air India: Civil Aviation Minister Vayalar Ravi Economic Times

No plans for Air India disinvestment: Vayalar Ravi domain-B

No Disinvestment in Air India: MinisterDaijiworld.com

Aviation Week - All India Radio

all 27 news articles »

-

Govt weighs Dutch auction

Business Standard - 5 days ago

"At this stage, it was too early to say whether Indiawould be able to meet its disinvestment target," he told the Economic Editors' conference here. ...Divestment: French auction back in Govt radarHindu Business Line

all 2 news articles »

-

Best way to divest - Mix retail with closed auction: Expert

Moneycontrol.com - 4 days ago

When people bid for Coal India, they knew all kinds of problems that Coal India has, ... Best way to divest - Mix retail with closed auction : Expert.

Keep up to date with these results:

- [PDF]

Mining Policy, Regulation and Conservation

File Format: PDF/Adobe Acrobat - Quick View

and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957. (MMDR ... -

List of various Central Labour Acts - Govt. of India

labour.nic.in/act/welcome.html20 Sep 2011 – Government of India, Ministry of Labour and Employment ... The Payment of Wages (AMENDMENT) Act, 2005. 2 ... 4. The Mines Act, 1952. 5 ...

-

Environmental Concerns in Mining Laws in India — National Law ...

www.nlsenlaw.org/mining/.../environmental-concerns-in-mining-law...12 Feb 2008 – I. THE MINES ACT, 1952:THE MINES RULES, 1955: ... 4) S. 4A (introduced by amendment in 1986 and came into effect from 10/2/1987) refers ...

- [PDF]

The Coal Mines Nationalisation Law (Amendment) Act, 1986

File Format: PDF/Adobe Acrobat - Quick View

Republic of India as follows:-- I. 1. (I) This Act may be called the Coal MinesNationalisation Laws. (Amendment) Act, 1986. T. (2) Save as otherwise expressly ...

-

List of Indian federal legislation - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Indian_federal_legislationCoal Mines Provident Fund and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1948, 46 ... Reserve Bank of India (Amendment and Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, 1953, 54 ...

-

Mining Amendment Bill 2008 - NSW Parliament

Act 2008 No 19, 20/05/2008; Assented 20/05/2008; ; ; An Act to amend the Mining ...to make further provision with respect to prospecting for and mining minerals.

-

India Together: Environmental Laws, Regulations and Policy ...

www.indiatogether.org/environment/laws.htmThe steel plant and port proposed by the South Korean mining giant in Orissa has remained on ... Running wild with the BD Act ... India's pro-asbestos position ...

- [DOC]

INDEX TO CENTRAL ENACTMENTS

File Format: Microsoft Word - Quick View

23 Jul 2010 – Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Amendment Act 1987 47. Ajmer Tenancy ... All-India Council for Technical Education Act 1987 52. All-India .....Coal Mines (Conservation and Development) Act 1974 28. Coal Mines ...

-

Legislation India (Lexadin)

20 Aug 1996 – The Mizoram Civil Court (Amendment) Act, 2007 · The Notaries Act ...The Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920 ... Mines and Minerals Act 1957 ...

-

New mining bill almost takes care of all

Moneycontrol.com - 2 Oct 2011

While the industry's pay-outs may shoot for the compensation fund and EPS cuts are being spoken about, S Vijay Kumar, mining secretary says the proposed Act ... Mining companies to take a hit of Rs 15000 crBusiness Standard

Stopping the loot The Hindu

India cabinet approves bill to share mining profitAFP

Chandigarh Tribune - Hindu Business Line

all 185 news articles »  NSE:COALINDIA -BOM:533278 - NSE:TATASTEEL

NSE:COALINDIA -BOM:533278 - NSE:TATASTEEL

-

Naveen eyes mining tax

Calcutta Telegraph - 2 days ago

Stating coal mining and thermal power plants cost Orissa economically, ... But our own election victory must never take precedence over India'svictory. ... Orissa CM Naveen Patnaik attends NDC meeting; calls on centre to ... Orissadiary.com

all 21 news articles »

-

RBI must fight inflation despite slowdown: Rangarajan

Hindustan Times - 5 days ago

India's economy will grow at a lower-than-expected pace of 8% during the fiscal year, ...citing coal shortages and problems in the miningsector. ... RBI must fight inflation despite slowdown - Rangarajan Reuters India

all 198 news articles »  PINK:CBSU

PINK:CBSU

-

India needs 100 Lavasas, but we'll crucify all who say so

Firstpost - 5 days ago

India needs a new urbanisation law as much as it needs a new Land Bill or a Mining Bill. Why do we need a Gulabchand to test the limits of the law to ...

-

China outplays Europe, US in Africa

Mail & Guardian Online - Roman Grynberg - 1 day ago

As India and China grow their economies, it is obvious they will not achieve ... Sysmin helped African countries weather declines in their mining sectors. ...

-

The seething India

GroundReport - Proloy Bagchi - 1 day ago

Acquisitions of fertile lands under an antique law for mining, industry and power ... He was, nonetheless, forced to act by an aggressive Supreme Court. ...

-

Indian business aircraft operators form industry body news

TravelBizMonitor - 1 day ago

By TBM Staff | Mumbai Business aircraft operators in India have set up a ... Industries like mining, oil and gas depend highly on business aviation for ...

-

Politician-corporates nexus greatest threat for Indian economy

Economic Times - 3 days ago

... connections could be an unchallengeable mix for creation of wealth in India. ... Mining Company, finds himself behind bars for alleged illegal mining. ...

-

Industry pushes for commercial mining in coal sector

Moneycontrol.com - 10 Oct 2011

Whereas, a private company can only do captivemining as per the Act, ... the current productivity in coal mining in India is one-tenth of the US, ... Industry chamber seeks transparency in coal allocation SME Times

all 10 news articles »

-

CBI sleuths raid NCL office, top execs' premises

Times of India - 3 days ago

CMD's secretary BSV Nair, NCL assistant general manager (mines-Amlodi project) ... NCL, which is the most profit-making subsidiary of the Coal India Limited ...  NSE:COALINDIA - BOM:533278

NSE:COALINDIA - BOM:533278

Keep up to date with these results:

-

New mining bill almost takes care of all

Moneycontrol.com - 2 Oct 2011

While the industry's pay-outs may shoot for the compensation fund and EPS cuts are being spoken about, S Vijay Kumar, mining secretary says the proposed Act ...Mining companies to take a hit of Rs 15000 crBusiness Standard

Stopping the loot The Hindu

India cabinet approves bill to share mining profitAFP

Chandigarh Tribune - Hindu Business Line

all 185 news articles » NSE:COALINDIA -BOM:533278 - NSE:TATASTEEL

NSE:COALINDIA -BOM:533278 - NSE:TATASTEEL

-

Naveen eyes mining tax

Calcutta Telegraph - 2 days ago

Stating coal mining and thermal power plants cost Orissa economically, ... But our own election victory must never take precedence over India'svictory. ...Orissa CM Naveen Patnaik attends NDC meeting; calls on centre to ... Orissadiary.com

all 21 news articles »

-

RBI must fight inflation despite slowdown: Rangarajan

Hindustan Times - 5 days ago

India's economy will grow at a lower-than-expected pace of 8% during the fiscal year, ...citing coal shortages and problems in the miningsector. ...RBI must fight inflation despite slowdown - Rangarajan Reuters India

all 198 news articles » PINK:CBSU

PINK:CBSU

-

India needs 100 Lavasas, but we'll crucify all who say so

Firstpost - 5 days ago

India needs a new urbanisation law as much as it needs a new Land Bill or a Mining Bill. Why do we need a Gulabchand to test the limits of the law to ...

-

China outplays Europe, US in Africa

Mail & Guardian Online - Roman Grynberg - 1 day ago

As India and China grow their economies, it is obvious they will not achieve ... Sysmin helped African countries weather declines in their mining sectors. ... -

The seething India

GroundReport - Proloy Bagchi - 1 day ago

Acquisitions of fertile lands under an antique law for mining, industry and power ... He was, nonetheless, forced to act by an aggressive Supreme Court. ... -

Indian business aircraft operators form industry body news

TravelBizMonitor - 1 day ago

By TBM Staff | Mumbai Business aircraft operators in India have set up a ... Industries like mining, oil and gas depend highly on business aviation for ... -

Politician-corporates nexus greatest threat for Indian economy

Economic Times - 3 days ago

... connections could be an unchallengeable mix for creation of wealth in India. ... Mining Company, finds himself behind bars for alleged illegal mining. ... -

Industry pushes for commercial mining in coal sector

Moneycontrol.com - 10 Oct 2011

Whereas, a private company can only do captivemining as per the Act, ... the current productivity in coal mining in India is one-tenth of the US, ...Industry chamber seeks transparency in coal allocation SME Times

all 10 news articles »

-

CBI sleuths raid NCL office, top execs' premises

Times of India - 3 days ago

CMD's secretary BSV Nair, NCL assistant general manager (mines-Amlodi project) ... NCL, which is the most profit-making subsidiary of the Coal India Limited ... NSE:COALINDIA - BOM:533278

NSE:COALINDIA - BOM:533278

Keep up to date with these results:

India clears policy to build new industrial zones

India passed a flagship policy on Tuesday to encourage manufacturing by streamlining labour and environmental rules in industrial parks, a move it says is key to create jobs and keep Asia's third-largest economy on a fast-growth track.

Business leaders welcomed the news, which will be a boost for Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, whose second-term agenda of big-ticket economic reforms has been knocked off course by corruption scandals and a lack of clear leadership.

With an eye to its emerging market rival China, India is desperate to ramp up goods exports and revamp a manufacturing sector that has struggled to be competitive since before economic liberalisation in 1991.

"China has done it, Germany has done it, now India has decided to do it," Trade Minister Anand Sharma told reporters after unveiling the policy to build at least seven new industrial parks.

India's economic boom has seen average economic growth of over 8 percent annually in recent years but job creation has been very low -- worrying for a country which needs to absorb about 20 million new workers each year.

Sharma said the new policy sought to create 100 million new jobs within a decade. In the same period, the government aims to lift manufacturing's share in gross domestic product to 25 from about 16 percent now, the level at which it has stagnated for more than 30 years.

The plan to slash regulation in at least seven special zones in the notoriously bureaucratic country has been in the works since last year but was held up by objections from the labour ministry, under fire from unions.

Dipanker Mukherjee, general secretary of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions, said the new policy was created without consulting workers and would be opposed "lock, stock and barrel" if it did not protect workers' rights.

But Confederation of Indian Industry said the new policy will "revolutionize" the manufacturing sector in the country and will help India head off a global economic slowdown.

"The announcement of the policy at this critical time would generate momentum, resulting in long term positive impact on growth aspirations," the industry lobby group's chief Chandrajit Banerjee said in a statement.

The zones will be developed by the federal and state governments along with the private sector to provide infrastructure such as ports and airports as well as freeing up labour rules -- including easing regulations on wage payouts if a company closes.

Union cabinet approves national manufacturing policyThe union cabinet Tuesday gave its nod to the national manufacturing policy that aims to create 100 million additional jobs by 2025 and develop mega industrial zones with world-class infrastructure facilities and flexible labour and environment regulations.

The Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs headed by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh approved the policy that also aims to increase the share of manufacturing in the economy to 25 percent from the current around 16 percent.

According to the policy, the government would help establish National Manufacturing Investment Zones with world-class infrastructure and investment friendly regulations to boost manufacturing activities.

"China has done it, Germany has done it, Japan has done it and now India has decided to do it," Commerce and Industry Minister Anand Sharma told reporters after the cabinet meeting here.

RBI deregulates savings deposit rate; cost of funds to rise

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on Tuesday deregulated savings deposit interest rate, the last administered bank rate in the economy, in a move which will push up cost of funds, sending bank shares sharply lower.

"It is felt that the time is appropriate to move forward and complete the process of deregulation of rupee interest rates," Reserve Bank of India said in its second-quarter monetary policy review. The deregulation is with immediate effect, the RBI said.

Currently, the savings rate stands at 4 percent, which was last raised in May after remaining unchanged for 8 years.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has stipulated that each bank will have to offer an uniform rate of interest on savings bank deposits upto 100,000 Indian rupees ($2,007). Above that, it may provide differential rates of interest.

The market gave a thumbs down to the proposal with shares of major lenders State Bank of India , HDFC Bank , Axis Bank , Bank of Baroda , Allahabad Bank

falling as much as 2-6 percent. The key banking sector index was down 2.66 percent in recent trade.

"It will definitely increase cost of funds for banks towards maintaining current account savings account deposit growth," Moses Harding, head of global markets group, IndusInd Bank said. IDBI Bankexecutive director R.K.Bansal said that he expects the savings rate to rise to 6 percent.

Bansal estimates that banks with lower share of savings rate deposits will take a 10-20 basis points hit on margins, while banks with larger share of savings account deposits will see a 40-50 basis points fall.

Already banks' cost of funds have gone up after the RBI mandated that banks calculate interest paid on savings deposits on a daily basis while the savings bank rate was last raised by 50 basis points.

Savings deposits are a source of low-cost funds for banks, which form 22 percent of banks' total deposit base and 13 percent of savings of the household sector.

This makes it a politically sensitive interest rate as savings deposits are held largely by households, particularly in rural areas where financial literacy is not widespread.

New age private banks are likely to aggressively move now to mop up low cost deposits, which traditionally has been the prerogative of the larger banks.

"We will have to digest it now," said N.S. Srinath, executive director, Bank of Baroda. "We will have to analyse the impact, because the gap between savings rate and term deposit rate is quite huge."

Term deposit rates are as high as 11 percent for several banks for some tenors making the spread over the savings rate large.

RBI had prepared a discussion paper last November on deregulation of savings bank deposit rate which spelt out both the pros and cons of deregulating the interest rates on savings deposit.

While RBI said that the deregulation will aid in monetary transmission, Indian lenders were not in favour of the proposal citing market volatility.

They had said they would be forced to raise transaction charges for ATM, money transfers and cheque books to protect margins.

($1 = 49.825 Indian Rupees)

Federal cabinet approves Rs 30 bn equity infusion in NABARD

Federal cabinet approved equity infusion of 30 billion rupees in state-run National Bankfor Agriculture and Rural Development or Nabard, information and broadcast minister Ambika Soni said on Tuesday.

The government has said it had plans to infuse capital in state-run banks and the largets lender State Bank of India is expected to receive funds worth 45-80 billion rupees by March 2012.

Mining Policy

India has newly proposed a mining policy which aims to curtail illegal mining and empower people settled in and around mining areas. The new Bill proposes that companies share 26% of the profits from mining with the locals who lose land. The Bill seeks to expedite the grant of mineral concessions in a transparent manner and attract big investments in the sector.

25 October 2011 Last updated at 22:14 GMT

Latest Articles on Mining Policy

Mining: Orissa seeks hike in royalty rates, ban on ore exportsBlaming the Centre's "lopsided policies" for tardy progress of the mineral-rich state, Orissa Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik on Saturday demanded an up...

Banning iron ore export from Goa one of the possibilities: Shah Commission

Putting a ban on the iron ore export from Goa is one of the possibilities explored by the Shah Commission during its investigations into the illegal m...

New policy for faster acquisition of overseas mineral assets

According to the secretary, companies with a three-year track record of profitability are covered by the policy.

More Articles about Mining Policy

03 Oct:Taxing time for India's metal, mining ...

01 Oct:

Mining Bill cleared; companies to shar...

30 Sep:

Land acquisition to become far easier ...

30 Sep:

Expecting some changes in the mining b...

30 Sep:

Cabinet approves new mining bill calli...

30 Sep:

Cabinet approves new Mining Bill calli...

30 Sep:

New mining law to give Rs 10,000 crore...

11 Sep:

New mines bill to be tabled in Parliam...

07 Sep:

Coal India operating 239 mines without...

07 Sep:

CIL draws flak from CAG for inadequate...

09 Aug:

Revised safety norms to be issued to m...

01 Aug:

SC notice to MoEF on suspension of Ste...

29 Jul:

President Pratibha Patil asks business...

19 Jul:

Mining without licence likely to cost ...

14 Jul:

People affected by Posco steel project...

11 Jul:

New mines bill to be sent for Cabinet ...

11 Jul:

Mines Ministry moots opening up minera...

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/fullcoverage/mining-policy

-

Department of Disinvestment - Ministry of Finance, Govt. of India

www.divest.nic.in/10 hours ago – Department of Disinvestment, Government of India. Arrow Promote people's ownership in CPSEs Arrow Ensure better Corporate Governance ...

You shared this on Blogger - 10 Jul 2011 -

2010: Year of bumper divestment - Times Of India

1 Jan 2011 – MUMBAI: The year 2010 will go down in the history of Indian markets as the one that witnessed the revival of the government divestment ...

-

Didi stays away as CIL, Hind Copper divestment okayed - Times Of India

16 Jun 2010 – RELATED ARTICLES. Coal India selloff may fetch govt Rs 10k ...

-

News for Divestment India

Zee NewsDisinvestment target may be missed: RBImydigitalfc.com - 23 hours agoBy Falaknaaz Syed Oct 24 2011 The government may missdisinvestment target of Rs ... said the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in its Macroeconomic and Monetary ...4 related articles -

'Reverse move to divest public stake in HAL' - Indian Express

www.indianexpress.com/news/reverse-move-to-divest.../848759/19 Sep 2011 – 'Reverse move to divest public stake in HAL' - The CPI(M) demanded that government rescind its decision to divest 10 per cent stake in ...

-

MMTC divestment by next fiscal: Sharma - Indian Express

www.indianexpress.com/news/mmtc-divestment-by-next.../735850/11 Jan 2011 – MMTC divestment by next fiscal: Sharma - Divestment in India ...

-

Business Line : Companies News : Scooters India divestment: Atul ...

22 Aug 2011 – The government's move to divest its stake in beleaguered ScootersIndia Ltd is running into rough weather, with another possible bidder Atul ...

-

Disinvestment of India

www.ircc.iitb.ac.in/~webadm/update/archives/.../disinvestment1.htmlNow, the Disinvestment Commission determines the share/bond price. Disinvested shares are listed, quoted and traded on the stock market. Indian and foreign ...

You shared this on Blogger - 9 Jul 2011 -

Divestment: India's new financial mantra? - Rediff.com Business

22 Jul 2009 – Presenting the Union Budget in Parliament recently, finance minister Pranab Mukherjee proposed estimated divestment proceeds of Rs 1120 ...

-

When was India's divestment ministry formed?

Although the process of divestment in India began right from 1991, a ...

-

Disinvestment - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DisinvestmentFor the privatization of state assets in India, see Privatization in India. For the routine business practice, see divestment. Disinvestment, sometimes referred to as ...

25 OCT, 2011, 03.59AM IST, ET BUREAU

India's coal economy will get a boost if private miners are allowed entry

Coal India Ltd.

BSE

324.65

00.00%

00.00

Vol:424758 shares traded

NSE323.90

-00.20%

-00.65

Vol:3614659 shares traded

Prices|Financials|Company Info|Reports

RELATED ARTICLES

- All CPSEs may get to decide on raw material purchase from abroad

- Shares of Coal India, Tata Steel, SAIL tank on mining bill approval

- Cabinet approves new mining bill calling for sharing profits, royalties with local communities

- Niche metal firms like Adhunik Metaliks, Monnet Ispat, Ess Dee Aluminium and others forge path to p...

- RIL maintains highest weightage in Sensex despite CIL overtaking it as No 1 company in M-Cap

In an interview to this paper, coal minister Sriprakash Jaiswal fretted that inefficiency, theft and graft consume at least a quarter of the output of state-owned behemoth Coal India (CIL). We agree with his diagnosis, but not with his incremental approach to boosting efficiency and cracking down on graft within CIL. There is a better way to do things. CIL today is a listed company, one of India's most valuable, with thousands of institutional and retail shareholders.

They will put pressure on CIL to do better and the company will have to respond. However, the coal mining giant lacks any rivals in the market and, therefore, any competitive fire in its belly. This is a lack that Jaiswal can address. He should devote all his energies to scrapping the 1973 law that nationalised all coal mines and helped create CIL. Today, 28 years after nationalisation, no player can vie with CIL to explore for coal or mine it.

The only exceptions, under two amendments made in 1976 and 1993, are for steelmakers and power producers who have access to captive coal mines, to extract the mineral and use it for fuel in their units. Both nationalisation and captive mining are policy disasters. It is time to do away with them.

Exploration and mining of minerals are specialised activities that should not be left to monopolies or companies for which mining is secondary. Mining companies should be allowed into coal mining, to compete with CIL and nudge it towards greater efficiency.

Makers of steel and power should buy iron ore or coal from miners and focus on their core areas of expertise. Worldwide, specialised miners have been seen to be more innovative and efficient extractors of minerals than if the activity is left to other companies. Steel companies, for example, will tend to focus their energies on making steel.

Mining, for them, will always be a least-cost, scrappy activity. India's total likely coal reserves are estimated at around 275 billion tonnes. Of this, only a fraction, 550 million tonnes, is used every year. A lot lies unexplored and we'll need advanced technology to mine many reserves that are now considered out of bounds. Let private investments from specialised miners come into the coal field.

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/opinion/coal-econ-to-get-a-boost-if-pvt-miners-are-allowed/articleshow/10481581.cms

-

Coal India Limited :: A Maharatna Company

www.coalindia.in/Coal India Limited :: A Maharatna Company. ... 03 August, 2011; Coal India's record stock liquidation 03 August, 2011; CIL's Annual Performance 2010-11 ...

-

Coal India Stock Price and Quotes - Coal India Company Profile

1 day ago – Coal India Stock prices, Stock quote of Coal India Ltd, Coal India stock news, Live Quote, Real time quote, investing data of Coal India stock ...

-

coal india: Latest News, Videos, Photos | Times of India

See coal india Latest News, Photos, Biography, Videos and Wallpapers. coal ...

-

News for coal india

Business StandardGovt to review Coal India's performance in DecemberEconomic Times - 32 minutes agoNEW DELHI: The government will review Coal India's performance again in December and also expressed hope that the PSU will record an all-round development ...11 related articles -

Coal India Stock Price, Share Price, Live BSE/NSE, Coal India Bids ...

Coal India Stock/Share prices, Coal India Live BSE/NSE, F&O Quote of Coal Indiawith Historic price charts for NSE / BSE. Experts & Broker view on Coal India ...

-

Government of India, Ministry of Coal

www.coal.nic.in/Describes the functions of the department, its organisational setup, and its agencies. -

Coal India Limited - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coal_India_LimitedCoal India Limited (CIL) (BSE: 533278, NSE: COALINDIA) is an Indian state-controlled coal company headquartered in Kolkata, West Bengal, India and the ...

-

South Eastern COalfields Limited

South Eastern Coalfields Limited is the largest coal producing company in the country. It is one of the eight subsidiaries of Coal India Limited (A Govt. of India ...

-

Coal India Ltd. Stock Price, Charts, Details and Latest ...

money.rediff.com/companies/coal-india-ltd/15110007Get Coal India Ltd. live share price, historical charts, volume, market capitalisation, market performance, reports and other company details.

-

India Coal Reserves Map

India Coal Reserves Map showing major Coal reserves in India with its international boundary.

-

Western Coalfields Limited

westerncoal.nic.in/Information on the group's activities, results, administration, and finances. -

Mining Bill ends Coal India's Bullish Uptrend | State of the Market

9 Jul 2011 – Coal India was having a great bullish ride since end Feb but mining bill could now change the trajectory of the stock for some time to.

Deepak Singh shared this -

palashbiswaslive: India on SALE! Coal India IPO Triggers ...

palashbiswaslive.blogspot.com/.../india-on-sale-coal-india-ipo-trigger...20 Oct 2010 – India on SALE! Coal India IPO Triggers Disinvestment Tsunami as SAIL, OIL India and ONGC on the Firing Line!Divestment may net Rs 59000 ...

You shared this

Ads

|

NRIs returning to India: Avail the benefits given under tax laws

EDITORS PICK

RELATED ARTICLES

- NRIs should plan their return to home as it has a bearing on the taxability of overseas income

- NRIs returning to India? Investment opportunities available are manifold

- NRIs guide to deal with inherited property

- NRI's guide to renting out property in India

- All about tax implications of overseas investments

By Girish Shetty & Abhishek Rao, Senior Tax Professionals, Ernst & Young

It is praise worthy weakness of a man to love the places where he played in his childhood, where he was educated, where he dwelt and call back to the mind his childhood pleasure. The recent fears of recession in the west compounded by the growth story in India, as well as the lure of returning to one's own motherland may change the minds of many Indians who have settled abroad to return to India permanently.

This may mean that they could be looking at resettling in India by selling their property abroad which they would have acquired whilst being there. This decision may not be just an emotional one but would have to factor other perspectives like taxation, exchange control regulations etc, which may significantly impact the decision of shifting back to India and its timing.

Subin, a person of Indian origin, was employed in the US for the past several years. He wants to return to India permanently. He owns several assets in the US such as a residential property, a car, and investment in shares in US based companies. He has also invested in mutual funds there. He is pondering on whether to sell his property in US before he returns to India permanently, but wants to get his car to India and if permitted, retain his investments in the US.

While discussing his idea of coming back to India permanently with a friend, he found out that there were certain advantages that he could derive in case he qualifies as a Non-Resident (NR) in India under theIndian tax laws. He also found out that the simplest way to qualify as a NR in India is to spend less than 60 days in India in any particular tax year, which runs from April 01 to March 31 of the subsequent calendar year. Accordingly, Subin has planned his return in such a way that he qualifies as a NR in India in the year in which he returns to India.

His decision to return to India would have both direct and indirect tax implications, such as income tax, wealth tax and customs duty. He would also need to take note of implications from an exchange control regulations perspective.

The implications under each of the above mentioned laws need to be understood distinctly. As per the Indian income-tax laws, NRs are taxable in India only on income which accrues in India or is received in India. In the case of an NR, once an income is earned and received outside India and it is brought to India at a later date, it would not be taxable in India.

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/nri/returning-to-india/nris-returning-to-india-avail-the-benefits-given-under-tax-laws/articleshow/10488516.cms

The Planning Commission today said that the economy could do better than 7.6 per cent growth for this fiscal as projected by the Reserve Bank of India in its half yearly monetary policy review.

"I think, it (economy) might do better 7.6 per cent (this fiscal. But you cannot rule out 7.6 per cent," Planning Commission Montek Singh Ahluwalia told reporters here.

The Reserve Bank today lowered the economic growth forecast to 7.6 per cent for the current fiscal. The central bank had earlier projected the Indian economy to grow by 8 per cent in 2011-12, lower than 8.5 per cent recorded in 2010-11.

"Slower global growth will have an adverse impact on domestic growth, particularly on industrial production, given the rising inter-linkages of the Indian economy with the global economy," RBI said in its Monetary Policy Review.

About the raising short-term lending and borrowing rate by 25 basis points (0.25 per cent), Ahluwalia said, "It is more or less on expected lines. They have rasied the repo rate by 25 basis point but RBI also said no more rate hike. I think that market can sense that this one more effort (to tame inflation)".

On deregulating the saving bank account interest rate, he said, "I have always been in favour of deregulating the saving banking (interest) rates. Keeping it fixed have been an illogical thing, so it is a good news".

The Reserve Bank today lowered theeconomic growth forecast to 7.6 per cent for the current fiscal even as it expressed hope that inflationwill start coming down from December.

"Slower global growth will have an adverse impact on domestic growth, particularly on industrial production, given the rising inter-linkages of the Indian economy with the global economy," RBI said in its Monetary Policy Review.

The RBI had earlier projected the Indian economy to grow by 8 per cent in 2011-12, lower than 8.5 per cent recorded in 2010-11.

"While growth in advanced economies is already weakening, there is a risk of sharp deterioration if a credible solution to the euro area debt problem is not found," RBI said.

Besides inflation, the RBI said slowdown in project investments was also impacting growth.

The overall inflation has remained above 9 per cent since December 2010. It was 9.72 per cent in September.

"Elevated inflationary pressures are expected to ease from December 2011. The projection for WPI inflation for March 2012 is kept unchanged at 7 per cent," RBI said.

The RBI also indicated that it might not go in for another rate hike in its mid-quarterly review in December 16, provided the inflation does not shoot up further.

"If the inflation trajectory conforms to projection, further rate hikes may not be warranted," RBI said.

It said that concerted policy focus is needed to generate adequate supply response in respect of items such as milk, eggs, fish, meat, pulses, oilseeds, fruits and vegetables.

"Structural imbalances in protein rich items will persist. Production of pulses this year is expected to be lower than last year. Consequently, food inflation is likely to remain under pressure," RBI said.

Food inflation, which account for 14 per cent in the overall inflation, stood at a six month high of 10.60 per cent.

The industry has said the 25 basis point rate hike by the Reserve Bank will further weaken economic growth, but expressed relief at the central bank's hinting at a pause in pushing up the lending rates.

The industry welcomed the RBI move to deregulate savings bank interest rates, a step which lenders said could fetch better returns for depositors as competition will intensify.

"Yet another interest rate hike (effected) by the RBI will further weaken economic growth and impact all other indicators," industry chamber AssochamPresident Dilip Modi said today.

However, the central bank has hinted that it may not hike the short term policy rates further.

"One of the main positives of the RBI policy is the indication that it will not raise policy rates further... The second positive is the savings rate deregulation which will give banks more freedom," CII Director General Chandrajit Banerjee said.

Expressing similar views, Ficci Secretary General Rajiv Kumar said, "There was a definite statement of intent from RBI on ruling out further rate increases in December.

"The deregulation of saving bank deposit rate is a welcome move and is likely to lead to increased product innovations across banks through more competition."

Ficci, however, expressed concern as to whether smaller banks would be able to compete in the market with the larger banks after this move.

RBI today hiked interest rates by 25 basis points. With this, the short term lending (repo) and borrowing (reverse- repo) rate now stand at 8.5 per cent and 7.5 per cent respectively. This is the 13th hike in a span of 20 months to tame inflation.

ELIGIBILITY TO COAL MINING

Amendments to Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973 already done to facilitate captive mining.

Under the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973 Coal mining was mostly reserved for the public sector. By an amendment to the Act in 1976, two exceptions to policy were introduced viz.(i) captive mining by private companies engaged in production of iron and steel and (ii) sub-lease for coal mining to private parties in isolated small pockets not amenable to economic development and not requiring rail transport. Considering the need to augment thermal power generation and to create additional thermal power capacity during the VIII Plan period, the Government decided to allow private participation in the power sector.

The Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973 was amended with effect from 9th June, 1993 to allow coal mining for captive consumption for generation of power, washing of coal obtained from a mine and other end uses to be notified by Government from time to time, in addition to the existing provision for captive coal mining for production of iron and steel. The amendment was carried out in Section 3(3)(a)(iii) of the Act by a Gazette Notification dated 9.6.93. Under the powers conferred on the Central Government by Section 3 (3) (a) (iii)(4) of the Act, another Gazette Notification has been issued on 15.3.96 to allow production of cement as an end use for captive mining of coal.

The June, 1993 amendment to the Act as well as the Gazette Notification of 15.3.96 apply to both the public sector and private sector companies desiring to mine coal for captive consumption. The restriction of captive mining does not apply to the Government-owned Coal Companies and mineral development like CIL and SCCL and the Mineral Development Corporations of the State Governments.

ELIGIBILITY

The eligibility to do coal mining in the country has been laid down in the provisions in Section 3 (3) of the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973. The parties eligible to do coal mining in India without the restriction of captive consumption are:-

The Central Government, a Government company (including a State Government company), a Corporation owned, managed and controlled by the Central Government.

A person to whom a sub-lease has been granted by the above mentioned Government, company or corporation having a coal mining lease, subject to the conditions that the coal reserves covered by the sub-lease are in isolated small pockets or are not sufficient for scientific and economic development in a coordinated manner and that the coal produced by the sub-lessee will not be required to be transported by rail.

2. As per the provisions in Section 3 (3) (a) (iii) of the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973, a company engaged in the following activities can do coal mining in India only for captive consumption:-

production of iron and steel

generation of power

washing of coal obtained from a mine, or

such other end use as the Central Government may, by notification, specify.

2.1 Under the powers vested with the Central Government by virtue of Section 3 (3)(a) (iii)(4) of the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973, a Gazette Notification was issued on 15.3.96 to provide cement production as an approved end-use for the purpose of captive mining of coal. Therefore, the cement producing companies are now eligible for undertaking coal mining for captive consumption.

2.2 In addition to Coal India Limited (CIL) and Singareni Collieries Company Limited (SCCL) , the following companies are also doing coal mining in India now:-

Tata Iron & Steel Company Limited (a captive coal mining company in the private sector)

Damodar Valley Corporation (a captive coal mining company in the public sector)

Indian Iron & Steel Company Limited (a captive coal mining company in the public sector)

Bihar State Mineral Development Corporation Limited (a non-captive coal mining company, a Government company under the control of Government of Bihar)

Jammu & Kashmir Minerals Limited (a non-captive coal mining company, a Government company under the control of Government of J&K)

Bengal Emta Coal Mines Limited (a captive coal mining company in the private sector)

Jindal Steel and Power Limited (a captive coal mining company in the private sector)

3. Special dispensations provided for setting up of associated coal companies by the end -user parties offered captive coal blocks .

Any of the companies engaged in any of the approved end-uses indicted in paras 2 and 2.1 above can itself mine coal from a captive coal block. Some of the private companies who were offered captive coal blocks expressed their difficulties to do coal mining in the country on the ground of lack of experience in coal mining. Keeping in view the difficulties experienced by such companies, the Government have now allowed the following dispensations:-

(a) A company engaged in any of the approved end-uses can mine coal from a captive block through an associated coal company formed with the sole objective of mining coal and supplying the coal on exclusive basis from the captive coal block to the end-user company, provided the end-user company has at least 26% equity ownership in the associated coal company at all times.

(b) There can be a holding company with two subsidiaries i.e. (i) a company engaged in any of the approved end-uses and (ii) an associated coal company formed with the sole objective of mining coal and supplying the coal on exclusive basis from the captive coal block to the end-user company, provided the holding company has at least 26% equity ownership in both the end-user company and the associated coal company..

Coal Mining Lease under the Mines and Minerals (Regulation & Development) Act, 1957.

Under the provisions of Section 5 (2) of the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973, the Coal India Limited enjoys the status of becoming the deemed lessee of the concerned State Governments in relation to all the nationalised coal mines. Under the provisions of Section 11 (2) of the Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition & Development) Act, 1957 also, the Coal India Limited acquires the same status of becoming deemed lessee of the concerned State Governments in relation to the lands over the coal bearing areas acquired under this Act. The deemed leases being in the nature of statutory leases, the Coal India Limited does not have to obtain separate leases under the MMRD Act, 1957 from the concerned State Government in respect of the nationalised mines and the coal bearing lands acquired under the CBA Act. However, in case any of the companies eligible to do coal mining in the country including CIL and the other Government and private coal companies want to acquire coal bearing lands under the Land Acquisition Act, 1894, they will be required to obtain coal mining leases from the concerned State Governments under the MMRD Act, 1957. Coal being a mineral listed in the First Schedule of the MMRD Act, 1957, the State Governments can grant coal mining leases only with the previous approval of the Central Government accorded under the proviso to Section 5 (1) of MMRD Act. Before the previous approval of the Central Government is accorded, the coal mining company is required to get the mining plan for the proposed coal mining area approved from the Central Government. The coal mining leases under the MMRD Act are now granted for 20-30 years initially and can be renewed for a further period of 20 years with the previous approval of the Central Government. The coal mining leases under the MMRD Act, 1957 are ordinarily subject to the a ceiling of 10 sq. kms. of area.

25 OCT, 2011, 04.44PM IST, ECONOMICTIMES.COM

RBI raises policy rates by 25 bps; home and auto loans

EDITORS PICK

- Govt extends 1% interest subsidy on home loans of up to Rs 15 lakh

- Diwali 2011: What's on offer for home buyers?

- Widening fiscal deficit triggers India downgrade fears

- RBI rate hike: Home & auto loans to get costlier

- 'Blue chips' need not always be safe investment choice

By PersonalFN

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in its quarterlymonetary policy review has raised policy rate by 25 bps or 0.25% on both Repo and Reverse Repo rates.

The anti-inflationary stance by the RBI has led to 13th consecutive rate hike in the last 18 months since March 2010.

The repo rate is the rate at which RBI lends to banks, now stands at 8.50%.

The reverse repo rate at which banks park their surplus with RBI now stands at 7.50%.

While the cash reserve ratio (CRR) remains unchanged at 6%.

This rate hike will make the cost of borrowing costlier for banks, who may in turn pass on the burden in the form of costlier borrowing to the end consumers or loan seekers. Home and auto loan EMIs will increase once banks start raising their base rate, while other loans like personal, education as well as the corporate loans are also likely to become costlier.

On the other hand, the announcement of deregulation of savings bank deposit interest rates (with immediate effect) will bring relief to the savers who maintain a huge surplus into their savings account to meet day to day requirement and contingency needs.

The RBI has however defined a slab of Rs. 1 lakh upto which the banks will offer uniform interest rate on savings bank deposits and provide differential rates of interest for deposits over Rs. 1 lakh.

This change will prove beneficial only to people who have and maintain huge surplus into their Savings account and will not benefit the lower income group or a savings account of the earning member of a middle level family.

So suppose you being in a high end bracket maintain a daily balance of Rs. 1,50,000/- into your savings account, then at the rate of 4% p.a. you would have earned a half yearly interest of Rs. 3,000/- over a period of 6 months.

Now with the new regulation coming in and say your bank offers interest rate @ 6% p.a. for your deposits over Rs. 1 lakh, then you will earn a half yearly interest of Rs. 3,500/- over a period of 6 months instead.

Your first Rs. 1 lakh deposit @ 4% p.a. will earn you a half yearly interest of Rs. 2,000/- and the next Rs. 50,000/- deposit @ 6% p.a. will earn you a half yearly interest of Rs. 1,500/-. So you earn an additional Rs. 500/- on half yearly basis on your immediate liquidity funds

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/analysis/RBI-raises-policy-rates-by-25-bps-home-and-auto-loans-to-get-costlier/articleshow/10487803.cms

| Mining has provided the answer to the manufacturing and energy needs of the humanity in the past century. Mining community around the world has contributed to the enrichment of the world through industrial development. Minerals are valuable natural resources being finite and non-renewable. They constitute the vital raw materials for many basic industries and are a major resource for development. Demand for minerals is expected to grow very fast, due to increasing levels of consumption, infrastructure development, and growth of the economy. Management of mineral resources has, therefore, to be closely integrated with the overall strategy of development and exploitation of minerals is to be guided by long-term national goals and perspectives. In India, 80% of mining is in coal and the balance 20% is in various metals and other raw materials such as gold, copper, iron, lead, bauxite, zinc and uranium. India with diverse and significant mineral resources is the leading producer of some of the minerals. India is not endowed with all the requisite mineral resources. Of the 89 minerals produced in India, 4 are fuel minerals, 11 metallic, 52 non-metallic and 22 minor minerals. India is the largest producer of mica blocks and mica splittings; ranks third in the production of coal & lignite, barytes and chromite; 4th in iron ore, 6th in bauxite and manganese ore, 10th in aluminium and 11th in crude steel. Iron-ore, copper-ore, chromite and or zinc concentrates, gold, manganese ore, bauxite, lead concentrates, and silver account for the entire metallic production. Limestone, magnesite, dolomite, barytes, kaolin, gypsum, apatite & phosphorite, steatite and fluorite account for 92 percent of non-metallic minerals. The index of mineral production, excluding fuel and atomic minerals, (base year 1993-94=100) for the year 2005-06 is expected to be 154.23 as compared to 153.48 in 2004-05. Life Indices: Important non-fuel Minerals

Regulation of Minerals Management of mineral resources in India is the responsibility of the Central Government and the State Governments in terms of Entry 54 of the Union List (List I) and Entry 23 of the State List (List II) of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution of India. The Central Government in consultation with the State Governments, formulates the legal measures for the regulation of mines and the development of mineral resources to ensure basic uniformity in mineral administration and to ensure that the development of mineral resources keeps pace, and is in consonance with the national policy goals. The regulation of mines and development of mineral resources in accordance with the national goals and priorities is the responsibility of the Central and State Governments. The role to be played by the Central and State Governments in regard to mineral development has been extensively dealt in the Mines and Minerals (Regulation and Development) Act, 1957 and rules made under the Act by the Central Government and the State Governments in their respective domains. The provisions of the Act and the Rules are reviewed from time to time and harmonised with the policies governing industrial and socio-economic developments in India. The Mines and Minerals (Regulation and Development) Act, 1957 lays down the legal frame-work for the regulation of mines and development of all minerals other than petroleum and natural gas. The Central Government has framed the Mineral Concession Rules 1960 for regulating grant of prospecting licences and mining leases in respect of all minerals other than atomic minerals and minor minerals. The State Governments have framed the rules in regard to minor minerals. The Central Government has also framed the Mineral Conservation and Development Rules, 1988 for conservation and systematic development of minerals. These are applicable to all minerals except coal, atomic minerals and minor minerals. National Mineral Policy A national mineral policy has evolved over the years in India. The policy emphasizes the need for conservation and judicious exploitation of finite mineral resources through scientific methods of mining, beneficiation and economic utilisation. Simultaneously, it keeps in view the present & future needs of defence and development of India and strives to ensure indigenous availability of basic and strategic minerals to avoid disruption of core industrial production in times of international strife. The basic objectives of the mineral policy in respect of minerals are: (a) to explore for identification of mineral wealth in the land and in off-shore areas; (b) to develop mineral resources taking into account the national and strategic considerations and to ensure their adequate supply and best use keeping in view the present needs and future requirements; (c) to promote necessary linkages for smooth and uninterrupted development of the mineral industry to meet the needs of India; (d) to promote research and development in minerals; (e) to ensure establishment of appropriate educational and training facilities for human resources development to meet the manpower requirements of the mineral industry; (f) to minimise adverse effects of mineral development on the forest, environment and ecology through appropriate protective measures; and (g) to ensure conduct of mining operations with due regard to safety and health of all concerned. According to the policy, induction of foreign technology and foreign participation in exploration and mining for high value and scarce minerals shall be pursued. Foreign equity investment in joint ventures in mining promoted by Indian companies would be encouraged. While foreign investment in equity would normally be limited to 50%, this limitation would not apply to captive mines of any mineral processing industry. Enhanced equity holding can also be considered on a case to case basis. In respect of joint venture mining projects of minerals & metals in which India is deficient or does not have exportable surplus, a stipulated share of production would have to be made available to meet the needs of the domestic market before exports from such projects are allowed. In case of ores whose known reserves are not abundant, preference will be given to those who propose to take up their mining for captive use. The policy also addresses certain aspects and elements like mineral exploration in the sea-bed, development of proper inventory, proper linkage between exploitation of minerals and development of mineral industry, protection of forest, preference to members of the scheduled tribes for development of small deposits in scheduled areas, environment and ecology from the adverse effects of mining, enforcement of mining plan for adoption of proper mining methods and optimum utilisation of minerals, export of minerals in value added form and recycling of metallic scrap & mineral waste. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| For Fee Based detailed analysis & value added information on this Sector, please contact us at info@IndiaCore.com |

http://www.indiacore.com/mining.html

Mining in India

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaThe Darya-i-Noor diamond from theIranian Crown Jewels, originally from the mines of Golconda, Andhra Pradesh.

Mining in India is an important economic activity which contributes significantly to the economy of India.[1] The mining sector underwent modernization following the independence of India although minerals have been mined in the region since antiquity.[1] The country exports a variety of minerals—found in abundance its geographically diverse regions—while it imports others not found in sufficient quantities within its geographical boundaries.[1] Several techniques for mining are employed in the country and a significant part of the country lies unexplored for mineral wealth.[1] Contents[hide] |

[edit]Overview

The tradition of mining in the region is ancient and underwent modernization alongside the rest of the world as India gained independence in 1947.[2] The economic reforms of 1991 and the 1993 National Mining Policy further helped the growth of the mining sector.[2] India's minerals range from both metallic and non-metallic types.[3] The metallic minerals comprise ferrous and non-ferrous minerals while the non metallic minerals comprise mineral fuels, precious stones, among others.[3]D.R. Khullar holds that mining in India depends on over 3100 mines, out of which over 550 are fuel mines, over 560 are mines for metals, and over 1970 are mines for extraction of nonmetals.[2] The figure given by S.N. Padhi is: 'about 600 coal mines, 35 oil projects and 6000 metalliferous mines of different sizes employing over one million persons on a daily average basis.'[4] Both open cast mining and underground mining operations are carried out and drilling/pumping is undertaken for extracting liquid or gaseous fuels.[2] The country produces and works with roughly 100 minerals, which are an important source for earning foreign exchange as well as satisfying domestic needs.[2] India also exports iron ore, titanium,manganese, bauxite, granite, and imports cobalt, mercury, graphite etc.[2]

Unless controlled by other departments of the Government of India mineral resources of the country are surveyed by the Indian Ministry of Mines, which also regulates the manner in which these resources are used.[5] The ministry oversees the various aspects of industrial mining in the country.[5] Both the Geological Survey of India and the Indian Bureau of Mines are also controlled by the ministry.[5] Natural gas, petroleum and atomic minerals are exempt from the various activities of the Indian Ministry of Mines.[5]

[edit]History

Indian coal production is the 3rd highest in the world according to the 2008 Indian Ministry of Mines estimates.[6] Shown above is a coal mine in Jharkhand.

Flint was known and exploited by the inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilization by the 3rd millennium BCE.[7] P. Biagi and M. Cremaschi ofMilan University discovered a number of Harappan quarries in archaeological excavations dating between 1985-1986.[8] Biagi (2008) describes the quarries: 'From the surface the quarries consisted of almost circular empty areas, representing the quarry–pits, filled with aeolian sand, blown from the Thar Desert dunes, and heaps of limestone block, deriving from the prehistoric mining activity. All around these structures flint workshops were noticed, represented by scatters of flint flakes and blades among which were typical Harappan-elongated blade cores and characteristic bullet cores with very narrow bladelet detachments.'[9] Between 1995 and 1998, Accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon dating dating of Zyzyphus cf. nummularia charcoal found in the quarries has yielded evidence that the activity continued into 1870-1800 BCE.[10]Minerals subsequently found mention in Indian literature. George Robert Rapp—on the subject of minerals mentioned in India's literature—holds that:

Sanskrit texts mention the use of bitumen, rock salt, yellow orpiment, chalk, alum, bismuth, calamine, realgar, stibnite, saltpeter,cinnabar, arsenic, sulphur, yellow and red ochre, black sand, and red clay in prescriptions. Among the metals used were gold,silver, copper, mercury, iron, iron ores, pyrite, tin, and brass. Mercury appeared to have been the most frequently used, and is called by several names in the texts. No source for mercury or its ores has been located. leading to the suggestion that it may have been imported.[11]

[edit]Geographical distribution

The distribution of minerals in the country is uneven and mineral density varies from region to region.[2] D.R. Khullar identifies five mineral 'belts' in the country: The North Eastern Peninsular Belt, Central Belt, Southern Belt, South Western Belt, and the North Western Belt. The details of the various geographical 'belts' are given in the table below:[12]| Mineral Belt | Location | Minerals found |

| North Eastern Peninsular Belt | Chota Nagpur plateau and theOrissa plateau covering the states of Jharkhand, West Bengal andOrissa. | Coal, iron ore, manganese, mica, bauxite, copper, kyanite, chromite, beryl, apatite etc. Khullar calls this region the mineral heartland of Indiaand further cites studies to state that: 'this region possesses India's 100 percent Kyanite, 93 percent iron ore, 84 percent coal, 70 percent chromite, 70 percent mica, 50 percent fire clay, 45 percent asbestos, 45 percent china clay, 20 percent limestone and 10 percent manganese.' |

| Central Belt | Manganese, bauxite, uranium, limestone, marble, coal, gems, mica, graphite etc. exist in large quantities and the net extent of the minerals of the region is yet to be assessed. This is the second largest belt of minerals in the country. | |

| Southern Belt | Karnataka plateau and Tamil Nadu. | Ferrous minerals and bauxite. Low diversity. |

| South Western Belt | Karnataka and Goa. | |

| North Western Belt | Rajasthan and Gujarat along theAravali Range. | Non-ferrous minerals, uranium, mica, beryllium, aquamarine, petroleum, gypsum and emerald. |

India has yet to fully explore the mineral wealth within its marine territory, mountain ranges, and a few states e.g. Assam.[12]

[edit]Minerals

The distribution of minerals in India according to the United States Geological Survey.

Along with 48.83% arable land, India has significant sources of coal (fourth-largest reserves in the world), bauxite, titanium ore, chromite, natural gas, diamonds, petroleum, and limestone.[13] According to the 2008 Ministry of Mines estimates: 'India has stepped up its production to reach the second rank among the chromite producers of the world. Besides, India ranks 3rd in production of coal & lignite, 2nd in barites, 4th in iron ore, 5th in bauxite and crude steel, 7th in manganese ore and 8th in aluminium.'[6]India accounts for 12% of the world's known and economically available thorium.[14] It is the world's largest producer and exporter of mica, accounting for almost 60 percent of the net mica production in the world, which it exports to the United Kingdom, Japan, United States of America etc.[15] As one of the largest producers and exporters of iron ore in the world, its majority exports go to Japan, Korea, Europe and theMiddle East.[16] Japan accounts for nearly 3/4 of India's total iron ore exports.[16] It also has one of the largest deposits of manganese in the world, and is a leading producer as well as exporter of manganese ore, which it exports to Japan, Europe (Sweden, Belgium, Norway, among other countries), and to a lesser extent, the United States of America.[17]

[edit]Production

The net production of selected minerals in 2005-06 as per the Production of Selected Minerals Ministry of Mines, Government of India is given in the table below:[edit]Exports

Mine shaft at Kolar Gold Fields.

The net exports selected of minerals in 2004-05 as per the Exports of Ores and Minerals Ministry of Mines, Government of India is given in the table below:| Mineral | Quantity | Unit | Mineral type |

| Coal | 403 | Million tonnes | Fuel |

| Lignite | 29 | Million tonnes | Fuel |

| Natural Gas | 31,007 | Million cubic metres | Fuel |

| Crude Petroleum | 32 | Million tonnes | Fuel |

| Bauxite | 11,278 | Thousand tonnes | Metallic Mineral |

| Copper | 125 | Thousand tonnes | Metallic Mineral |

| Gold | 3,048 | Thousand grammes | Metallic Mineral |

| Iron Ore | 140,131 | Thousand tonnes | Metallic Mineral |

| 93 | Thousand tonnes | Metallic Mineral | |

| Manganese Ore | 1,963 | Thousand tonnes | Metallic Mineral |

| 862 | Thousand tonnes | Metallic Mineral | |

| Diamond | 60,155 | Non Metallic Mineral | |

| Gypsum | 3,651 | Thousand tonnes | Non Metallic Mineral |

| Limestone | 170 | Thousand tonnes | Non Metallic Mineral |

| 1,383 | Thousand tonnes | Non Metallic Mineral | |

| Mineral | Quantity exported in 2004-05 | Unit | |

| 896,518 | tonnes | ||

| Bauxite | 1,131,472 | tonnes | |

| Coal | 1,374 | tonnes | |

| Copper | 18,990 | tonnes | |

| Gypsum & plaster | 103,003 | tonnes | |

| Iron ore | 83,165 | tonnes | |

| Lead | 81,157 | tonnes | |

| Limestone | 343,814 | tonnes | |

| Manganese ore | 317,787 | tonnes | |

| Marble | 234,455 | tonnes | |

| Mica | 97,842 | tonnes | |

| Natural gas | 29,523 | tonnes | |

| Sulphur | 2,465 | tonnes | |

| Zinc | 180,704 | tonnes |

[edit]Issues with Minings

One of the most challenging issues in India's mining sector is the lack of assessment of India's natural resources.[12] A number of areas remain unexplored and the mineral resources in these areas are yet to be assessed.[12] The distribution of minerals in the areas known is uneven and varies drastically from one region to another.[2] India is also looking to follow the example set by England, Japan and Italy to recycle and use scrap iron for ferrous industry.[18]Under the British Raj a committee of experts formed in 1894 formulated regulations for mining safety and ensured regulated mining in India.[4] The committee also passed the 1st Mines act of 1901 which led to a substantial drop in mining related accidents.[4] The accidents in mining are caused both by man-made and natural phenomenon, for example explosions and flooding.[19] The main causes for incidents resulting in serious injury or death are roof fall, vehicular accidents, falling/slipping and hauling related incidents.[20]

In recent decades, mining industry has been facing issues of large scale displacements, resistance of locals, environmental issues like pollution, corruption, deforestation, dangers to animal habitats.[21][22][23][24][25]

[edit]Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Khullar, 631-633

- ^ a b c d e f g h Khullar, 631

- ^ a b Khullar, 632-633

- ^ a b c Padhi, 1019

- ^ a b c d Annual Report (2007-2008), Ministry of Mines, chapter 4, page 4

- ^ a b India's Contribution to the World's mineral Production (2008), Ministry of Mines, Government of India. National Informatics Centre.

- ^ Biagi, page 1856

- ^ Biagi, 1857

- ^ Biagi, 1858

- ^ Biagi, 1860

- ^ Rapp, 11

- ^ a b c d Khullar, 632

- ^ "CIA Factbook: India". CIA Factbook.

- ^ "Information and Issue Briefs - Thorium". World Nuclear Association.

- ^ Khullar, 650-651

- ^ a b Khullar, 638

- ^ Khullar, 638-640

- ^ Khullar, 659

- ^ Padhi, 1020

- ^ Padhi, 1021

- ^ http://www.freewebs.com/epgorissa/

- ^ http://www.indiawaterportal.org/post/9431

- ^ http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/content/goas-mining-problems

- ^ http://sp.lyellcollection.org/cgi/content/abstract/250/1/141

- ^ http://www.indiatogether.org/environment/mining.htm

[edit]Bibliography

- Annual Report (2007-2008), Ministry of Mines, Government of India, National Informatics Centre.

- Biagi, Paolo (2008), "Quarries in Harappa", Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures (2nd edition) edited by Helaine Selin, pp. 1856–1863, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- Padhi, S.N. (2003), "Mines Safety in India-Control of Accidents and Disasters in 21st Century", Mining in the 21st Century: Quo Vadis? edited by A.K. Ghose etc., Taylor & Francis,ISBN 90-5809-274-7.

- Rapp, George Robert (2002), Archaeomineralogy, Springer, ISBN 3-540-42579-9.

- Khullar, D.R. (2006), "Mineral Resources", India: A Comprehensive Geography, pp. 630–659, Kalyani Publishers, ISBN 81-272-2636-X.

- Lyday, T. Q. (1996), The Mineral Industry of India, United States Geological Survey.

- Find Indian Mining related information at a single place

- Indian Mining Industry - News and Analysis.

- Resources on Mining, India environment portal

[show]v · d · eEconomy of India

View page ratings

Rate this page

What's this?

Trustworthy

Objective

Complete

Well-written

I am highly knowledgeable about this topic (optional)

Submit ratings

Categories:

Vedanta Resources

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaVedanta Resources plc

Type Public limited company

Traded as LSE: VED Industry Mining and Resources Founded 1976, Bombay, India Founder(s) Anil Agarwal Headquarters London, United Kingdom Area served Worldwide Key people Anil Agarwal

(Executive Chairman)

Navin Agarwal

(Deputy Executive Chairman)

Mahindra Mehta

(CEO)Products Copper, aluminium, zinc, lead, gold, iron ore, pig iron and metallurgical coke Revenue  US$7.873 billion (2010)[1]

US$7.873 billion (2010)[1]Operating income  $1.653 billion (2010)[1]

$1.653 billion (2010)[1]Profit  $598 million (2010)[1]

$598 million (2010)[1]Total assets  $23.887 billion (2010)[1]

$23.887 billion (2010)[1]Total equity  $11.357 billion (2010)[1]

$11.357 billion (2010)[1]Employees 30,000 (2010)[1] Subsidiaries Sterlite Industries

BALCO

HZL

Sesa Goa

MALCO

Vedanta Aluminium

Sterlite Energy

Australian Copper Mines

Konkola Copper MinesWebsite Vedantaresources.com Vedanta Resources plc (LSE: VED) is a global mining and metals company headquartered in London, United Kingdom. It is the largest mining and non-ferrous metals company in India and also has mining operations in Australia and Zambia.[2] Its main products are copper,zinc, aluminium, lead and iron ore.[2][3] It is also developing commercial power stations in India in Orissa (2,400 MW) and Punjab (1,980 MW).[4]

It is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index.

Contents

[hide][edit]History

The company was founded by Anil Agarwal in Mumbai in 1976.[5] It was first listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2003 when it raised $876 million through an Initial Public Offering.[6] Meanwhile in 2006 it acquired Sterlite Gold, a gold mining business.[7] It raised an additional $2bn through an ADR issue in 2007.[8] In 2008 it bought certain of the assets of Asarco, a copper mining business, out of Chapter 11 for $2.6bn.[9]

[edit]Operations

[edit]Copper

Sterlite Industries (India) Ltd.: Sterlite is registered office headquartered in Tuticorin, India. Sterlite has been a public listed company in India since 1988, and its equity shares are listed and traded on the NSE and the BSE, and are also listed and traded on the NYSE in the form of ADSs. Vedanta owns 53.9% of Sterlite and have management control of the company.

Konkola Copper Mines: Vedanta own 79.4% of KCM's share capital and have management control of the company. KCM's other shareholder is ZCCM Investment Holdings Plc. The Government of Zambia has a controlling stake in ZCCM Investment Holdings Plc.

Copper Mines of Tasmania Pty Ltd.: CMT is headquartered in Queenstown, Tasmania. Sterlite owns 100.0% of CMT and has management control of the company.

[edit]Zinc

Hindustan Zinc Limited: HZL is headquartered in Udaipur in the State of Rajasthan. HZL's equity shares are listed and traded on the NSE and BSE. Sterlite owns 64.9% of the share capital in HZL and has management control. Sterlite has a call option to acquire the Government of India's remaining ownership interest.

[edit]Aluminium

Bharat Aluminium Company Ltd.: BALCO is headquartered at Korba in the State of Chhattisgarh. Sterlite owns 51.0% of the share capital of BALCO and has management control of the company. The Government of India owns the remaining 49.0%. Sterlite exercised an option to acquire the Government of India's remaining ownership interest in BALCO in March 2004.

Vedanta Aluminium Ltd.: Vedanta Aluminium is headquartered in Jharsuguda, State of Orissa. Vedanta owns 70.5% of the share capital of Vedanta Aluminium and Sterlite owns the remaining 29.5% share capital of Vedanta Aluminium. Vedanta Aluminium produces ingots, billets & wire rods that are sold in the markets around the World.

Madras Aluminium Company Ltd.: MALCO is headquartered in Mettur, India. MALCO's equity shares are listed and traded on the NSE and BSE. They own 93.9% of MALCO's share capital and have management control of the company.

[edit]Iron ore

Sesa Goa Limited: Sesa Goa is headquartered in Panaji, India, and its equity shares are listed and traded on the NSE and BSE. Vedanta owns 57.1% of Sesa and have management control of the company.

[edit]Commercial power generation business

Sterlite Energy Limited: Sterlite Energy is headquartered in Mumbai. Sterlite owns 100.0% of Sterlite Energy and has management control of the company.

[edit]Criticism

[edit]Environmental damage

Vedanta has been criticised by human rights and activist groups, including Survival International and Amnesty International, due to their operations in Niyamgiri Hills in Orissa, India that are said to threaten the lives of the Dongria Kondh that populate this region.[10] The Niyamgiri hills are also claimed to be an important wildlife habitat in Eastern Ghats of India as per a report by the Wildlife Institute of India[11] as well as independent reports/studies carried out by civil society groups.[12] In January 2009, thousands of locals formed a human chain around the hill in protest at the plans to start bauxite mining in the area.[13] The Union Environment Ministry in August 2010 rejected earlier clearances granted to a joint venture led by the Vedanta Group company Sterlite Industries for mining bauxite from Niyamgiri hills.[14]