Rural Mutiny, FARM CRISIS and Cereally challenged Indian Economy ...

blogs.ibibo.com/.../rural-mutiny-farm-crisis-and-cereally-challenged-indian-economy - Cached - Similar -

Gloria Steinem, Clinton's tears, and rural India - Sepia Mutiny

www.sepiamutiny.com/sepia/archives/004951.html - Cached - Similar -

Red or Green? - Sepia Mutiny

www.sepiamutiny.com/sepia/archives/004121.html - Cached - Similar -

Rural Mutiny, FARM CRISIS And Cereally Challenged Indian Economy ...

finalads.com/.../Rural+Mutiny,+FARM+CRISIS+and+Cereally+challenged+Indian+Economy - Cached - Similar -

Mutiny.in » Source Pilani: Empowering Rural India

mutiny.in/2008/11/05/source-pilani-empowering-rural-india/ - Cached - Similar -

Mutiny.in » Rural WiMax In India. Courtesy, Intel Corp

Intel will fit the center with specially designed "India PCs" that are made to withstand the constant powercuts, heat and dust in rural India. ...mutiny.in/2006/11/.../rural-wimax-in-india-courtesy-intel-corp/ - Cached - Similar -

Blue man in a Red district: A rural GOP mutiny?

buildourparty.blogspot.com/2008/03/rural-gop-mutiny.html - Cached - Similar -

Extremists regroup in Bangladesh's rural northwest | open ...

www.opendemocracy.net/india/news_digests/190609 - Cached - Similar -

CUBAN RURAL GUARDS MUTINY; Object to Transfer to Permanent Army ...

query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res... - Similar -

Zimbabwe turns to teenagers to combat mutiny

www.inthenews.co.uk/.../zimbabwe-turns-teenagers-combat-mutiny-$1272106.htm - Cached - Similar -

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Next |

Land Reform in India: Part 1

- 12:08amwww.landaction.org/display.php?article=57 - Cached - Similar -

Issues of Land Reforms in India

www.naukrihub.com/hr-today/land-reforms.html - Cached - Similar -

T he National Government, since independence has

In addition to having a concurrent evaluation on various aspects of land reforms in India by the Land. Reforms Unit, now known as 'Centre for Rural Studies' ...

rural.nic.in/book98-99/chapter.8.pdf - Similar -

Land Reform in India: Issues and Challenges

ported benefits of the current World Bank land reform agenda in India. ...... land reform in India will continue to be one of struggle and hope. It will be ...

www.foodfirst.org/files/bookstore/pdf/promisedland/4.pdf - Similar -

Tenancy Reforms in India - Author - Jayant Bhatt

www.legalserviceindia.com/articles/tena_agr.htm - Cached - Similar -

Land reforms in India: constitutional and legal approach (with ... - Google Books Result

In England, the feudalism had taken over the British life defeating the cause of land reforms. But with the gradual switch over to the socialistic way of ...

books.google.co.in/books?isbn=8185880093... -

Land Reform in India

www.inwent.org/E+Z/1997-2002/de202-8.htm - Cached - Similar -

Land Reforms | India Environment Portal

www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/taxonomy/term/76 - Cached - Similar -

Land Reform, Poverty Reduction, and Growth: Evidence from India ...

www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/003355300554809 - Similar -

by T Besley - 2000 - Cited by 206 - Related articles - All 28 versions

Land Reforms in India | Land Reform Act – India Housing

www.indiahousing.com/legal-aspects/land-reform.html - Cached - Similar -

| Searches related to: land reforms in india | |||

| land reforms in andhra pradesh | agrarian land reform | land reform in west bengal | land tenure reform |

| land reforms in kerala | property laws india |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Next |

|

|

Land Acquisition in India | Land Acquisition Act of India – India ...

Get full info on Land Acquisition in India with main focus on Land Acquisition Acts, Process, Procedure, Bill, Definition and so on.

www.indiahousing.com/legal-aspects/land-acquisition.html - Land Acquisition Act - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

21 Sep 2009 ... The Land Acquisition Act of 1894 is a legal Act in India which allows the Government of India to acquire any land in the country. ...

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_Acquisition_Act - India and sore points in land acquisition

21 Mar 2007 ... They allege, among other things, discrimination in the selection of land for acquisition and the amount of compensation. ...

www.rediff.com/money/2007/mar/21guest1.htm - India Together: Legislative Brief on the Land Acquisition ...

19 May 2008 ... The Land Acquisition Act, 1894 addresses the process of land acquisition in India and was last amended by the Land Acquisition Amendment Act ...

www.indiatogether.org/2008/may/law-land.htm - Towards Reform of Land Acquisition Framework in India

4 May 2007 ... Downloadable! We bring out the fundamental and more important problems with the current framework of land acquisition in India, ...

ideas.repec.org/p/iim/iimawp/2007-05-04.html - Land Acquisition | India Environment Portal

9 Oct 2009 ... With the world's biggest steel producer Arcelor Mittal expressing serious resentment over the delay in land acquisition in Jharkhand and ...

www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/taxonomy/term/90 - Process of Land Acquisition

15 Aug 2008 ... The Process of Land Acquisition The difficulties that come in the process of Land Acquisition in India are immense, given the population ...

www.legalserviceindia.com/.../l257-Process-of-Land-Acquisition.html - Report on Amendment to Section 6 of the Land Acquisition Act, 1894

6 of the Land Acquisition Act, 1894, which has come to light in view of the decision of the Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court of India in its ...

lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/182rpt.pdf - EPW

Towards Reform of Land Acquisition Framework in India (2nd June 2007). Sebastian Morris , Ajay Pandey. Current land prices are highly distorted owing ...

www.epw.org.in/epw/uploads/articles/10686.pdf - SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE & LAND ACQUISITION IN INDIA | SEZ REQUIRES ...

SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE & LAND ACQUISITION IN INDIA Read SEZ REQUIRES DEBATE Blogs, SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE & LAND ACQUISITION IN INDIA Blogs at Ibibo Blogs.

blogs.ibibo.com/.../special-economic-zone-amp-land-acquisition - Searches related to: Land Acquisition in India land acquisition act 1894 india land acquisition sez compulsory acquisition land purchase land in india land development india land acquisition act india land purchase loan india

You have removed results from this search. Hide them Loading...

www.indiahousing.com/legal-aspects/land-acquisition.html -

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_Acquisition_Act -

www.rediff.com/money/2007/mar/21guest1.htm -

www.indiatogether.org/2008/may/law-land.htm -

ideas.repec.org/p/iim/iimawp/2007-05-04.html -

www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/taxonomy/term/90 -

www.legalserviceindia.com/.../l257-Process-of-Land-Acquisition.html -

lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/182rpt.pdf -

www.epw.org.in/epw/uploads/articles/10686.pdf -

blogs.ibibo.com/.../special-economic-zone-amp-land-acquisition -

| Searches related to: Land Acquisition in India | |||

| land acquisition act 1894 india | land acquisition sez | compulsory acquisition land | purchase land in india |

| land development india | land acquisition act india | land purchase loan india |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Next |

Migration and Human Development

The Human Development Report 2009 breaks some myths about migration. View Full Article

Issue : VOL 44 No. 41 and 42 October 10 - October 23, 2009

EDITORIALS

Migration and Human Development

Regulating Executive Compensation?

Enabling the Disabled

From 50 Years Ago (10 October 2009)

LETTER FROM SOUTH ASIA

Democracy Does the Heavy Lifting, Handle It with Care

COMMENTARY

The Dinakaran Imbroglio: Appointments and Complaints against Judges

Recent Trends in Indian GDP and Its Components: An Exploratory Analysis

Reservations within Reservations: A Solution

Can Poor States Afford the Fiscal Responsibility Legislation?

Policy Options for India's Edible Oil Complex

BOOK REVIEWS

Gender Aspect of Ramnabami-Natak

Pakistan: Identity and Islamic Ideology

PERSPECTIVES

Dealing with Effects of Monsoon Failures

SPECIAL ARTICLES

How Much 'Carbon Space' Do We Have? Physical Constraints on India's Climate Policy and Its Implications

Tejal Kanitkar , T Jayaraman , Mario DSouza , Prabir Purkayastha , D Raghunandan , Rajbans Talwar

Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: The Case of BSNL

Kerala's Education System: From Inclusion to Exclusion?

Disability Law in India: Paradigm Shift or Evolving Discourse?

Renu Addlakha , Saptarshi Mandal

NOTES

Mapping Indian Districts across Census Years, 1971-2001

Hemanshu Kumar , Rohini Somanathan

DISCUSSION

Intellectual Bilingualism

CURRENT STATISTICS

Macroeconomic Indicators (10 October 2009)

Foreign Trade: Imports and Exports by Commodities

Secondary Market Transactions in Government Securities and the Forex Market – September 2009

Clearing Corporation of India Limited

Money Market Activity: Rising Trends

Clearing Corporation of India Limited

LETTERS

Planned Military Offensive

Arundhati Roy , Amit Bhaduri , Sandeep Pandey , Colin Gonsalves , Dipankar Bhattacharya , and Others

Gruesome Killing

Moushumi Basu , Gautam Navlakha

REAPPRAISAL

A new resonance

In his views on crucial issues pertaining to economic development, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar comes across as a radical economist who would have staunchly opposed the neoliberal reforms being carried out in India since the 1990s.

VENKATESH ATHREYA

DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR was among the most outstanding intellectuals of India in the 20th century in the best sense of the word. Paul Baran, an eminent Marxist economist, had made a distinction in one of his essays between an "intellect worker" and an intellectual. The former, according to him, is one who uses his intellect for making a living whereas the latter is one who uses it for critical analysis and social transformation. Dr. Ambedkar fits Baran's definition of an intellectual very well. Dr. Ambedkar is also an outstanding example of what Antonio Gramsci called an organic intellectual, that is, one who represents and articulates the interests of an entire social class.

While Dr. Ambedkar is justly famous for being the architect of India's Constitution and for being a doughty champion of the interests of the Scheduled Castes, his views on a number of crucial issues pertaining to economic development are not so well known. Dr. Ambedkar was a strong proponent of land reforms and of a prominent role for the state in economic development. He recognised the inequities in an unfettered capitalist economy. His views on these issues are found scattered in several writings; of these the most important ones are his essay, "Small Holdings in India and Their Remedies" and an article, "States and Minorities". In these writings, Dr. Ambedkar elaborates his views on land reforms and on the kind of economic order that is best suited to the needs of the people.

Dr. Ambedkar stresses the need for thoroughgoing land reforms, noting that smallness or largeness of an agricultural holding is not determined by its physical extent alone but by the intensity of cultivation as reflected in the amounts of productive investment made on the land and the amounts of all other inputs used, including labour. He also stresses the need for industrialisation so as to move surplus labour from agriculture to other productive occupations, accompanied by large capital investments in agriculture to raise yields. He sees an extremely important role for the state in such transformation of agriculture and advocates the nationalisation of land and the leasing out of land to groups of cultivators, who are to be encouraged to form cooperatives in order to promote agriculture.

Intervening in a discussion in the Bombay Legislative Council on October 10, 1927, Dr. Ambedkar argued that the solution to the agrarian question "lies not in increasing the size of farms, but in having intensive cultivation that is employing more capital and more labour on the farms such as we have." (These and all subsequent quotations are taken from the collection of Dr. Ambedkar's writings, published by the Government of Maharashtra in 1979). Further on, he says: "The better method is to introduce cooperative agriculture and to compel owners of small strips to join in cultivation."

During the process of framing the Constitution of the Republic of India, Dr. Ambedkar proposed to include certain provisions on fundamental rights, specifically a clause to the effect that the state shall provide protection against economic exploitation. Among other things, this clause proposed that:

* Key industries shall be owned and run by the state;

* Basic but non-key industries shall be owned by the state and run by the state or by corporations established by it;

* Agriculture shall be a state industry, and be organised by the state taking over all land and letting it out for cultivation in suitable standard sizes to residents of villages; these shall be cultivated as collective farms by groups of families.

As part of his proposals, Dr. Ambedkar provided detailed explanatory notes on the measures to protect the citizen against economic exploitation. He stated: "The main purpose behind the clause is to put an obligation on the state to plan the economic life of the people on lines which would lead to highest point of productivity without closing every avenue to private enterprise, and also provide for the equitable distribution of wealth. The plan set out in the clause proposes state ownership in agriculture with a collectivised method of cultivation and a modified form of state socialism in the field of industry. It places squarely on the shoulders of the state the obligation to supply the capital necessary for agriculture as well as for industry."

Dr. Ambedkar recognises the importance of insurance in providing the state with "the resources necessary for financing its economic planning, in the absence of which it would have to resort to borrowing from the money market at high rates of interest" and proposes the nationalisation of insurance. He categorically stated: "State socialism is essential for the rapid industrialisation of India. Private enterprise cannot do it and if it did, it would produce those inequalities of wealth which private capitalism has produced in Europe and which should be a warning to Indians."

ANTICIPATING criticism against his proposals that they went too far, Dr.. Ambedkar argues that political democracy implied that "the individual should not be required to relinquish any of his constitutional rights as a condition precedent to the receipt of a privilege" and that "the state shall not delegate powers to private persons to govern others". He points out that "the system of social economy based on private enterprise and pursuit of personal gain violates these requirements".

Responding to the libertarian argument that where the state refrains from intervention in private affairs - economic and social - the residue is liberty, Dr. Ambedkar says: "It is true that where the state refrains from intervention what remains is liberty. To whom and for whom is this liberty? Obviously this liberty is liberty to the landlords to increase rents, for capitalists to increase hours of work and reduce rate of wages." Further, he says: "In an economic system employing armies of workers, producing goods en masse at regular intervals, someone must make rules so that workers will work and the wheels of industry run on. If the state does not do it, the private employer will. In other words, what is called liberty from the control of the state is another name for the dictatorship of the private employer."

India's experience with neoliberal reforms since 1990 shows that Dr. Ambedkar's apprehensions regarding the implications of the unfettered operation of monopoly capital, both domestic and foreign, were far from misplaced. As has been documented and written about extensively, during this period of neoliberal reforms, there has been no breakthrough in the rate of economic growth. At the same time, there has been a distinct slowing down of the rate of growth of employment and practically no decline in the proportion of people below the poverty line. Agriculture has been in a crisis for some time now and the rate of growth of industry has also been declining for several years now. At the same time, despite a slower growth of foodgrains output, the government is saddled with huge excess stocks, which it seeks to sell abroad or to domestic private trade at very low prices.

The government and its economists, instead of recognising that the crisis is the product in large part of the policies of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation, propose a set of so-called second-generation reforms. At the centre of these reforms is the complete elimination of employment security. The war cry of the liberalisers is: "Away with all controls and the state, and let the market rule."

In this context, one cannot but recall Dr. Ambedkar's words that liberty from state control is another name for the dictatorship of the private employer. Whether on labour reforms or on agrarian policy or on the question of the insurance sector or the role of the public sector in the context of development, Dr. Ambedkar's views are in direct opposition to those of neoliberal policies.

It is indeed a pity that self-styled leaders of Dalit movements, who invoke Dr. Ambedkar's name day in and day out, do not examine carefully his views on key issues of economic policy and their contemporary relevance for the struggles of the oppressed. One may not expect much from those Dalit-based political forces which think nothing of cohabiting with the Sangh Parivar, but even many sections of the Dalit movement which proclaim a radical stance on social (and sometimes economic) issues do not raise the question of land or of the role of the state in the sharp manner in which Dr. Ambedkar does.

Dr. Venkatesh Athreya is Professor and Head of the Department of Economics, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchi.

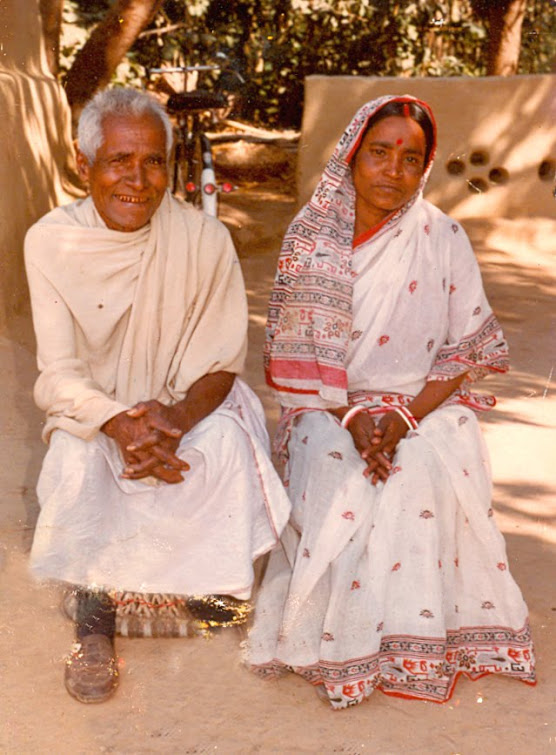

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, also called Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar in affection and respect, was born in 1891 in a Mahar Untouchable family and died in 1956 after a lifetime of service to his people and to India. His influence has spread throughout India and his image, a Western-dressed gentleman pointing to the future and carrying a book, is found in many villages and all cities. The book represents the Constitution of independent India. His followers know the facts of his life and are so reverential that one right wing critic called him a 'false God'. The word now used broadly for Untouchables, Tribals, and other low castes and classes is 'Dalit', which means ground down, but began a proud use in the 1970s with a literary movement called 'Dalit Sahitya', made famous at first by the 'Dalit Panthers' named in reference to the militant American 'Black Panthers'. Like the word 'Black', it can be a source of controversy today. The term coined by Mohandas K. Gandhi, 'Harijan' or people of God, was resented by Ambedkar as patronizing, and the two also clashed over the idea of separate electorates for untouchables; Gandhi's win is still resented by some as depriving Dalits of their chosen leaders. Dr. Ambedkar's influence may be seen in literature, in educational and political institutions, in a massive Buddhist conversion, and in increased pride and self-confidence among Dalits.

| Experts seek land ceiling like Bengal | |

| CITHARA PAUL | |

New Delhi, Oct. 24: The Centre has been asked to impose the Bengal model of land distribution across the country by a panel it appointed to suggest land reforms. The non-binding advice, which recommends rural land ceilings more stringent than those in Bengal, comes at a time the Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee government has tried to raise those limits to promote industry but seen its efforts stalled. The panel, set up by the rural development ministry, also discourages the use of farmland for industry. Stating that "land ceiling as a re-distributive programme is of as much relevance today as it was 50 years ago'', the committee has recommended limiting personal landholdings to 5-10 acres of irrigated land or 10-15 acres of non-irrigated land. In Bengal, the ceiling in non-irrigated areas is 17 acres and in irrigated areas, 12 acres. Left-ruled Bengal, Kerala and Tripura are the only states with rural land ceilings, the limit for irrigated land in Kerala being 15 acres. Some other states have tried and failed to enact land ceilings. So, although the report on "State Agrarian Relations and the Unfinished Task in Land Reforms" was handed in last January, the Centre has been unwilling to reveal its contents given their controversial nature. The standard reply from officials has been: "The ministry is going through the recommendations and will reveal them at the appropriate time." The commission was formed as a follow-up to the National Land Reforms Council, set up by the Prime Minister in 2008. It was headed by rural development minister C.P. Joshi and included experts such as A.K. Singh of Lucknow's Giri Institute of Development Studies, B.K. Sinha of the National Institute of Rural Development and P.K. Jha of the School of Economic Sciences and Planning, JNU. Although the recommendations are not binding, sources said, the report is significant since the rural development minister heads the committee. The panel has not mentioned the debate over whether smaller landholdings — a necessary impact of a ceiling — bring down productivity in the long run. Many economists believe the debate has been clinched as Bengal, Kerala and Tripura witnessed marked rise in productivity after land reforms. After the land re-distribution in Bengal in the late 1970s, the yield had increased 60 per cent, with economists attributing it to the extensive cultivation possible on smaller plots and the new owners' enthusiasm. However, some others still argue that smaller holdings make it uneconomical to use expensive farm technology, such as tractors. But that argument applies only to advanced capital-intensive agriculture, a very small part of India's agrarian economy. Bengal's Left Front government, the architect of the land reforms in the state, recently tabled a bill in the Assembly to relax the rural ceiling to facilitate commercial farming, farm products business and other industry. The bill has been sent to a House panel that has not been able to take a decision yet. Joshi's panel has made a slew of other recommendations (see chart). A potentially controversial one is the suggestion to scrap the exemptions to religious, educational, charitable and industrial organisations. Various educational and religious institutions have been acquiring land across the country using the exemptions granted by state governments. The panel says religious institutions should be allowed only a single unit of 15 acres. Criticising the widespread conversion of farmland for non-agriculture purposes, the committee says this has led to a fall in food production. "The inequitable distribution of benefits from the new land use, insufficient quantity of compensation, and rehabilitation not operationalised properly are leading to enormous dissatisfaction among the project-affected people. This ultimately is leading to gruesome social unrest as witnessed across the country and such violence can escalate and spread… if the conversion of land is not addressed relevantly," it says. It recommends that cultivable land should be the last option when acquisition is done, and if such land has to be taken over, the consent of all stakeholders is a must. The committee has also questioned the land re-distribution initiatives undertaken by various state governments apart from Bengal, Kerala and Tripura. It says "the land assigned to the poor were mostly uncultivable, and where cultivable lands have been assigned they were not under their possession''. It adds that the Bhoodan movement initiated by Acharya Vinoba Bhave in the 1950s faced major blocks since most of the land donated was not good enough for cultivation and in most cases, much of the donated land did not reach the poor. It asks state governments to do a survey to ascertain the current status of these plots. Suggesting a new round of land redistribution, the committee says "the list of beneficiaries in fresh assignments should be selected by (the) gram sabha''. It has suggested a single-window approach to redistribution of ceiling-surplus land. The panel has also cited the "massive encroachments on government land'' in the Sunderbans in Bengal and the Aravalli and Satpura regions of Madhya Pradesh. The panel is also concerned that "the corpus of tribal land is in serious danger of erosion''. It says 4.3 million hectares of forestland have been diverted for non-forest use and that 55 per cent of this diversion has taken place after 2001. It recommends that the gram sabhas be recognised as the competent authority for all matters relating to transfer of tribal land. According to the panel, the autonomous district councils in the Northeast have failed to perform their task. "There is an urgent need for codification of the traditional rights of the village councils." |

The Other Side of Babasaheb Ambedkar - The Maker of the Indian Constitution

Dr. Ravindra Kumar - 12/6/2007

Babasaheb Ambedkar is principally known for his voice raised for upliftment of Dalits and down-trodden section of society and the work he did for them. Secondly, he is remembered for his ability and competence as the Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly, formed to frame the Constitution of India. Indeed, his both of these works were of great importance and every right thinking and righteous Indian is proud of his performance and had profound regard for him.

However, Dr. Ambedkar's endeavours and works of upliftment of Dalits and other weaker sections of society and as architect of Indian Constitution is not the only introduction of his personality. In fact, it is only one aspect of his personality. The other side of his personality can be evaluated as seen through his thoughts, understanding and suggestions for land reforms in this predominantly agriculturist country, foreign policy, the State of Jammu and Kashmir in particular, and his work for strengthening nationalism in India.

It is an irony that most of the people are acquainted with only one aspect of Ambedkar's life and works. It is also ridiculous that even this side of his personality is used for fulfillment of pure political purposes. As Dr. Ambedkar never used politics for personal gains, it is wholly unjustified to use his name to meet political ends. Besides this, it is not proper to ignore the other side of his personality particularly in view of over all national interests.

Dr. Ambedkar's proclaimed determination in favour of Indian nationalism is reflected in his often repeated words, "I am an Indian, India is my motherland and nothing is supreme than this to me" and it is a self proven fact too. However, there were many other occasions when his determined stand in favour of Indian nationalism proved that he was a patriot par excellence.

When it was proposed in the Constituent Assembly to continue the provision of separate constituencies for a particular religious community, Babasaheb Ambedkar vehemently opposed it keeping the idea of national interest in his mind. In 1948, when Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was working hard with determination to merge the State of Hyderabad with the Union of India, some people attached to a particular ideology tried to misguide State's Scheduled Castes to favour the Nizam. At that time, Dr. Ambedkar said, "Scheduled Castes should not put their community up with disgrace and defamation/humiliation by siding with Nizam who is anti India." Simultaneously, after independence, in the year 1949, he called upon the countrymen to be bewaring of the activities of neighbouring country and called them "to remain determined to safeguard the freedom of India till last drop of blood."

An ardent supporter of land reforms and profitable agriculture, Dr. Ambedkar called for modernization of this sector ever since the third decade of twentieth century. Side by side, analyzing Indian foreign policy he said, "Thrust of our foreign policy is to solve problems of other nations rather than our own." Linking Kashmir problem with this policy, he opined, "Even if we cannot defend the entire region, at least our own people should be accorded full protection."

Babasaheb Ambedkar cautioned the Government several times about expansionist design of China. He did not agree with Indian policy makers' belief of Panchasheela as basis of our relationship with China and said, "Mao Tse-Tung does not have faith in Panchasheela, which is an essential part of Buddhism. If he has any belief in this ideal, he would have well treated Buddhist of his own country."

Undoubtedly, Ambedkar was a champion of social reforms. Along with this he was a great nationalist and a patriot. He was thorough and through a humanist. He always paid due regards to others. His respect for Mahadeo Govind Ranade, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Savarkar and Sardar Patel is well-known. He had also regarded Balasaheb Kher and K. M. Munshi. Much is said about relationship betwixt Gandhiji and Babasaheb Ambedkar. But despite differences of opinion, Ambedkar had regards for the Mahatma. On September 6, 1954 he had said in the Upper House –Rajya Sabha, "I respect Gandhiji. After all he was very near to untouchables and loved them."

It is high time that we must be well acquainted with all aspects of Dr. Ambedkar's great personality before we talk of remembering him in true sense and following his ideals.

| Dr. Ravindra Kumar is a universally renowned Gandhian scholar, Indologist and writer. He is the Former Vice-Chancellor of University of Meerut. |

Backgrounder Part I: Land Reform in India

Issues and Challenges

January 21, 2003

India inherited a semi-feudal agrarian system. The ownership and control of land was highly concentrated in a few landlords and intermediaries whose main intention was to extract maximum rent, either in cash or kind, from tenants. As a result, agricultural productivity suffered and oppression of tenants resulted in a progressive deterioration of their plight.

| Land Research Action Network | (More from this organization) |

|

Page: 1 | 2

Brief Historical

Purview

As the

basis of all economic activity, land can either serve as an essential

asset for the country to achieve economic growth and social equity,

or it could be used as a tool in the hands of a few to hijack a

country's economic independence and subvert its social processes.

During the two centuries of British colonization, India had

experienced the latter reality. During colonialism, India's

traditional land ownership and land use patterns were changed to ease

acquisition of land at low prices by British entrepreneurs for mines,

plantations etc. The introduction of the institution of private

property de-legitimized community ownership systems of tribal

societies. Moreover, with the introduction of the land tax under the

Permanent Settlement Act 1793, the British popularized the zamindari

system at the cost of the jajmani relationship that the landless

shared with the land owning class. By no means a just system, the

latter at least ensured the material security of those without land.7

Owing to these

developments, at independence, India inherited a semi-feudal agrarian

system. The ownership and control of land was highly concentrated in

a few landlords and intermediaries whose main intention was to

extract maximum rent, either in cash or kind, from tenants. Under

this arrangement, the sharecropper or the tenant farmer had little

economic motivation to develop farmland for increased production.

Naturally, a cultivator who did not have security of tenure, and was

required to pay a high proportion of output in rents, was less likely

to invest in land improvements, or use high yielding varieties or

other expensive inputs likely to yield higher returns. At the same

time, neither was the landlord particularly concerned about improving

the economic condition of the cultivators. As a result,

agricultural productivity suffered and oppression of tenants resulted

in a progressive deterioration of their plight.

In the years

immediately following India's independence, a conscious process of

nation building looked upon problems of land with a pressing urgency.

In fact, the national objective of poverty abolition envisaged

simultaneous progress on two fronts, high productivity and equitable

distribution. Accordingly, reforms of the land were visualized as an

important pillar for a strong and prosperous country. The first few

five-year plans allocated substantial budgetary amounts for the

implementation of land reforms. A degree of success was even

registered in certain regions and states, and especially in areas

like the abolition of intermediaries, protection to tenants,

rationalization of different tenure systems and the imposition of

ceiling on land holdings. Fifty-four years down the line, however,

a number of problems are still far from satisfactorily resolved.

Most studies

indicate that inequalities have increased, rather than decreased.

The number of landless labor has gone up and the top ten percent

monopolizes more land now than in 1951. Meanwhile, the issue of land

reforms has over the years, either unconsciously faded from public

mind or deliberately been glossed over. Vested interests of the

landed elite and their powerful nexus with the political-bureaucratic

system have blocked meaningful land reforms and /or their earnest

implementation. The oppressed have either been co-opted with some

benefits, or further subjugated as the new focus on LPG has altered

government priorities and public perceptions. As a result, we are

today at a juncture where land, mostly for the urban, educated elite,

and who also happens to be the powerful decision-maker, has become

more a matter for housing, investment and infra-structure building.

In the bargain, the existence of land as a basis of livelihood -- for

subsistence, survival, social justice and human dignity has largely

been lost.

Objectives

It is against this background that

the specific objectives of the Project in India have been articulated

as:

-

To raise popular and elite awareness

on issues related to land, particularly in the present context of

the LPG thrust of the government since the 1990s -

To monitor specific projects and

programmes being aided by international financial institutions in

some states of India in order to assess their true impact on the

rural community directly affected. -

To monitor and scrutinize national

and transnational economic trends that have a specific bearing on

issues related to land and agriculture. -

To explore the

efficacy of the current developmental model that perceives land only

as a factor of production, and not as a means of survival, equity

and dignity. -

To examine possible strategies for

facilitating reconciliation between the claims of the market over

land and land reforms to ensure social change based on justice and

equity. -

To document

historical strategies of land reforms and place them in the

socio-economic-political context in which they were effective or not

and accordingly cull out lessons for the future. -

To recommend alternative policies

and approaches to contemporary land challenges. -

To provide research and analytical

support to the existing land movements, and facilitate better

networking among them. -

To awaken the weakening social

consciousness of an increasingly consumerist society by drawing

linkages between the economic policies of globalization at the macro

level and its impact on human livelihoods at the micro level.

IFIs and Issues

Related to Land in India

The task of the

articulation of objectives is several times easier compared to the

challenges that lie ahead in realizing these goals. Any

reform is as difficult an economic exercise as a political

undertaking since it involves a realignment of economic and political

power. The groups that are likely to be the losers naturally resist

reallocation of power, property and status. Obviously, the

landholding class is unlikely to willingly vote itself out of

possession. Neither should it be expected that it would be uniformly

inflamed by altruistic passions to voluntarily undertake the

exercise. Hence, one cannot underestimate the complexity of the task

at hand.

Loopholes in

legislation have facilitated the evasion of some of the provisions,

for instance in ceiling reforms, by those who wanted to maintain the

status quo. At the same time, tardy implementation at the

bureaucratic level and a political hijacking of the land reforms

agenda have traditionally posed impediments in the path of effective

land reforms. Even in states that have attempted reforms, the

process has often halted mid-way with the cooption of the

beneficiaries by the status quoits to resist any further reforms.

For instance, with the abolition of intermediary interests, the

erstwhile superior tenants belonging mostly to the upper and middle

classes have acquired a higher social status. Rise in agricultural

productivity, rising land values and higher incomes from cultivation

have added to their economic strength. These classes have since

become opposed to any erosion in their newly acquired financial or

social status.

Hence,

problems related to land such as concentration, tenancy rights,

access to the landless etc still continue to challenge India. The

criticality of the issue, in fact, may be gauged from the fact that

notwithstanding the decline in the share of agriculture to the GDP,

nearly 58% of India's population is still dependant on agriculture

for livelihood. More than half of this percentage (nearly 63%),

however, owns smallholdings of less than 1 hectare while the large

parcels of 10 hectares of land or more are in the hands of less than

2%. The absolute landless and the near landless (those owning up to

.2 ha of land) account for as much as 43% of the total peasant

households.8

This reality,

however, had come to worry the governments little during the late

1970s and 80s. It was only in the 1990s, with the initiation of the

economic restructuring process that the issue of land reforms

resurfaced, albeit in a different garb and with a different objective

and motivation. If the government-led land reforms had been imbued

with a degree, though the extent is debatable, of desire for

attaining equity, social justice and dignity, the new land reforms

agenda is market-driven, as everything else in this phase of economic

globalization, and has at its heart certain other kinds of

objectives. Being promoted and guided by various IFIs, contemporary

emphasis on land reforms reflects and seeks to fulfill the

macro-economic objectives of these multilateral economic

institutions.

While the return of

land reforms to the government's list of priorities is a welcome

development, the manner in which it is being undertaken, its

objectives, and consequently the impact on people, especially those

that are already marginalized and are being further deprived of a

stake in the system, raises a number of questions and prompts one to

look for alternatives. The Project, therefore, shall devote its

energies to identifying and monitoring the implementation of certain

specific IFI-sponsored programmes in particular states with a view to

examining their short-term and long-term impact on the lives and

livelihoods of local residents. This shall enable an informed

critique of the IFI- led land reforms programmes and serve as a

lesson for peoples else where in India and in other regions of the

globe as well.

Market- Led Land

Reforms -- The Current Emphasis on Land Administration, Titling and

Registration

In

their analyses of India's land reforms programme, most IFIs have

highlighted that one of the basic problem that the rural poor face is

access to land and security of tenure. Consequently, they advocate

redemption of this situation through structural reforms of property

rights to create land markets as part of a broader strategy of

fostering economic growth and reducing rural poverty.9

A large emphasis

has, therefore, been placed on the need to establish the basic legal

and institutional framework that would improve secure property rights

as a means to protect environmental and cultural resources, to

facilitate productivity-enhancing exchanges of land in rental and

sales markets, to link land to financial markets, to use land as a

sustainable source of revenue for local governments, and to improve

land access by the poor and traditionally disenfranchised. (Emphasis

added).

The package the

IFIs offer includes comprehensive reforms of land tenure, including

titling, cadastral surveys and settlement operations, land

registries, improvements in land revenue systems, land legislation,

land administration, land sale-purchase transactions, and removal of

restrictions on land leasing. In fact, it may be recalled that even

in 1975, a Land Reforms Policy Paper brought out by the WB had

described land registration and titling as the main instruments for

increasing individual's tenure security, the main facilitators for

the establishment of flourishing land markets and the major tools to

enable the use of land as collateral for credit. However, the

emphasis on these issues then was much less. But today, these

ingredients constitute the mainstay of IFI-led land reforms across

the world.

Through this

approach, land reforms are envisaged in two phases:

-

Phase One -- Dismantling

Distortionary Policies.

-

This would

involve the removal of all restrictions on the sale and purchase of

land, including those related to minimum and maximum size, and

revision of procedures for sale of public lands. -

It would

envisage the complete elimination of rent controls so as to increase

investments and efficiency in agriculture. -

Zoning would also be eliminated,

except in the case of safeguarding certain environmental concerns.

Restrictions on land use, if necessary in specific areas, would be

achieved through instruments other than government legislations,

such as creation of a market for development rights.

-

Phase Two-

Institutional and Legal Reforms

-

Constraints in the operations of

the land markets to be removed through reforms that aim that

reducing costs of land adjudication, issuing of correct titles, and

easy availability of crucial market information to interested

parties. -

Creation of land laws that remove

uncertainty facilitates easy and transparent access to the land

administration system, establish dispute settlement institutions

and institutionalize property rights.

-

As is evident, the

bottom line of all these measures is the facilitation of land markets

wherein land is available for sale-purchase from less to more

productive users. It is believed that with proper title deeds

being available for property, it would become easier and less risky

to buy and sell land. As a private commodity, the owner will have a

stake in putting the land to best use, which in WB terminology

implies use that can generate maximum profits.

The manner in which

this exercise would generate access to land for the rural poor is

through the provision of credit to them for purchase of land, making

available to them technical assistance to enable them to plough the

land in keeping with the needs of commercial farming, and providing

them with marketing support. Of course, everything would come for a

price with the farmer being gradually pushed into a process of

indebtedness. Credit would be easily available to have access to

land and other expensive agricultural inputs such as seeds,

fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation, market mechanisms etc. The

market forces at every step would encourage the farmer to take easily

available loans, but vagaries of nature as much as those of the

market could easily bring him to ruin. Bankrupt, he may be forced to

sell the land and either move out of the land market completely,

leaving the fields for the richer and more able farmers/corporations,

or get into the process once again to try his luck.

It is in this

context that the market-driven land reforms that are being encouraged

by the IFIs need to be looked into. None can deny the need for

reform in land administration agencies, for updating of land records

through surveys and settlement of rights, computerization of land

records etc. In fact, one can recall that in the first two decades of

government land reforms after independence, the reformers demanded

these measures. At that time, however, the issues were largely

ignored or neglected owing to lack of institutional support such as

trained staff, equipment, capital etc. The IFIs have rightly

discovered this lacuna and are now offering the financial help and

technical expertise in carrying out the exercise. However, the

purpose for which these reforms are being undertaken in the present

context raises several issues since the motives may not measure up to

those of social justice and dignity for the individual:

1. The IFIs

proclaim increasing access to land for the rural poor by offering

credit. However, how does this help if they simultaneously encourage

macroeconomic and trade policies that negate the benefits of such an

exercise? Policies such as trade liberalization, cutbacks in price

supports and subsidies for food producers, privatization of credit,

commercialization of agriculture, excessive export promotion and

promotion of research in expensive technologies such as genetic

engineering etc undercut the economic viability of the smaller and

poorer farmers. The onslaught of these policies adversely affects

the small farmers leading to high failure rates, mass sell-offs,

increased landlessness, land concentration, even intensified land

degradation, and rural-urban migration. What then is the efficacy of

such land reforms?

2. The

emergence of land markets and the consequent commodification of land

raises several issues for the status of the common property

resources because by codifying social and property relations that

were hitherto implicit, land titling could reduce the

asset-endowment of vulnerable groups with inadequate access to

political power. Therefore, their privatization would spell severe

consequences for those who have survived on it for generations but

have no legal documents to show for the same. Does this not lead to

situations, where common lands may be acquired by powerful

individuals/corporations in violation of long-established rights of

indigenous communities?

3. What impact

would the process of titling and land registration have on the

status of women and indigenous people who often tend to be left out

of these processes?

4. The

market-driven economy emphasizes short-term profit motives with

little regard for the people or environment. Rather, the primacy of

commercial interests in a market society encourages the view that

stretches of densely vegetated forests or other open lands that may

have an intangible ecological value but are not being utilized to

carry out activities that can fetch tangible foreign exchange are

‘non-optimally used resources.' With such perceptions becoming

prevalent, would not the environment, too, become victim to a

thoughtless extraction of maximum profits with little consideration

for the actual ecological value of land? For instance, the

conversion of non-agricultural land to agricultural, or vice versa,

may not be the most judicious use of the land but may be resorted to

for the sake of maximizing profits.

5. The benefits

of secure titles to land may be nullified by market distortions

caused when land is used as a commodity for investment and

speculation. This then inflates land value, making access to land

even more difficult. Therefore, how can land speculation, an

inevitable accompaniment of land market development, help in

providing secure tenure for all -- the major World Bank motivation

for market-led land reforms?

While data is not

yet available, most observers feel that the net result of the

predominance of land markets in regions where they have become

operative has been a deterioration in the access of the poor to land

as they are forced/tempted to sell off land they own, or lose it by

defaulting on credit. None can argue against the need for

straightening land records and the provision of secure land titles

and registration, the motivation for the exercise must delve deeper

than the mere creation of land markets for private profit. The

Project proposes to undertake a study of this issue and its actual

impact on the rural poor by studying the implementation of the

activity in the state of Maharashtra. It also proposes to study

alternative schemes in this regard, such as the one undertaken by the

Maharashtra government in Pune. The simultaneous analysis of two

different methods of undertaking regularization of land records would

reveal lessons for others. It shall also weigh the benefits costs of

these measures against those of land redistribution as a means of

poverty alleviation and for promotion of ecological sustainability.

Commercialization

/ Industrialization of Agriculture

An economic model based on widespread

industrialization has signified profound changes in the manner in

which agriculture is conducted and for what purpose. From a family,

or at the most a community affair, agriculture has been

"professionalised"

into an industry where a farmer produces for a global market. Indeed,

modern techniques of farming such as increased mechanization,

development and widespread use of artificial fertilizers, pesticides

and herbicides, emphasis on economies of scale through larger field

and farm size, continuous cropping, developments in livestock, plant

breeding and biotechnology have transformed agriculture.

This phenomenon has

been promoted by decision-makers who perceive agriculture more as an

industry that must be conducted to maximize profits and less as a way

of life that has social and ecological ramifications. The trend has

been justified by the substantial increases in agricultural output,

which, it is argued, has substantially eased national food security

concerns. Undoubtedly, national granaries are today overflowing. And

yet, the individual in the village is starving to death or a ‘failed'

farmer is resorting to suicide. Surely, this calls for a closer

examination of the issues involved.

Commercialization

of agriculture first struck its root in India in the 1960s with the

Green Revolution in Punjab when the World Bank, along with the U.S.

Agency for International Development (USAID), promoted agricultural

productivity through import of fertilizers, seeds, pesticides and

farm machinery.10

The Bank provided the credit that was needed to replace the low-

cost, low-input agriculture in existence with an agricultural system

that was both capital- and chemical-intensive. The Indian government

decided that the potential of the new technology far outweighed the

risks and accordingly, the foreign exchange component of the Green

Revolution strategy for the five-year plan period (1966-1971) was

raised to about $2.8 billion, a jump of more than six times the total

amount allocated to agriculture during the preceding third plan.11

Most of the foreign exchange was spent on imports of fertilizer,

seeds, pesticides and farm machinery.

World Bank credit

subsidized these imports while also exerting pressure on the

government to obtain favorable conditions for foreign investment in

India's fertilizer industry, import liberalization and the

elimination of most domestic controls. The Bank advocated the

replacement of diverse varieties of food crops with monocultures of

imported varieties of seeds. In 1969, the Terai Seed Corporation was

started with a $13 million World Bank loan. This was followed by two

National Seeds Project (NSP) loans. This program led to the

homogenization and corporatization of India's agricultural system.

The Bank provided NSP $41 million between 1974 and 1978. The projects

were intended to develop state institutions and to create a new

infrastructure for increasing the production of Green Revolution seed

varieties. In 1988, the World Bank gave India's seed sector a fourth

loan to make it more "market responsive." The $150 million

loan aimed to privatize the seed industry and open India to

multinational seed corporations. After the loan, India announced a

New Seed Policy that allowed multinational corporations to penetrate

fully a market that previously was not as directly accessible.

Sandoz, Continental, Cargill, Pioneer, Hoechst and Ciba Geigy now are

among the multinational corporations that have major interests in

India's seed sector.

While the Revolution

did ease India's food grain situation, transforming the country from

a food importer to an exporter, it also provided space to the rich

farming community to politicize subsidies, facilitate concentration

of inputs increase dependence on greater use of

external inputs such as credit, technology, seeds, fertilizers etc.

Moreover, a study by the World Resources Institute, published in

1994, showed that the Green Revolution only increased Indian food

production by 5.4% while the agricultural practices that were

followed have resulted in nearly 8.5 million hectares or six percent

of the crop base being lost to water logging, salinity or excess

alkalinity. Furthermore, although the amount of wheat production has

doubled over a period of 20 years, and rice production has gone up by

50%, greater emphasis has been placed on production of commercial

crops like sugarcane and cotton etc at the expense of crops like

chickpeas and millet that were traditionally grown by the poor for

themselves. This has steadily eroded the self-sufficiency of the

small farmer in food grains.

Yet, governments

remain stuck on the same model of agrarian reforms and are being

generously encouraged by the IFIs. Agriculture is the World Bank's

largest portfolio in any country. 130 agricultural projects have

received $10.2 billion Bank financing in India since the 1950s.

These projects have taken the form of providing support for the

fertilizer industry, ground water exploitation through pump-sets,

introduction of high yielding variety of seeds, setting up of banking

institutions to finance capitalist agriculture etc.

Not surprisingly,

then, the trend towards commercialization of agriculture has only

intensified and in the process given rise to a number of questions:

-

Has not the

promotion of the modern concept of agrarian reforms resulted in a

radical transformation of agricultural practices through the

introduction of new seed varieties, cultivation of cash crops,

increasing use of fertilizers and chemicals and the charging of

user-fees for irrigation and drinking water etc and thereby resulted

in a sharp division in the farming community between the prosperous

agri-business farmers and the small farmers trying to keep pace with

market demands of commercial agriculture?

-

There is also a

tendency to monopolize different agricultural activities, including

production and distribution of seeds, knowledge etc. In addition,

with liberalization, comes the entry of foreign capital into the

farming sector, either through direct control over production or

through contract farming. Corporate and contract farming encourages

the cultivation of cash crops and fruits instead of food crops on

even small pieces of land. Will this not steadily erode the

self-sufficiency of the small farmer in the area of food grains?

More so, if the cash crop fails, the small farmer is not adequately

covered by any policy of the government, thereby becoming as

vulnerable to natural vagaries as to market forces. Also, would not

increased production translate into lower prices for products

because of the simple demand-supply law, thereby making it even more

difficult for small and marginal farmers to redeem the high costs of

production?

-

Would not the lack of economic viability in the farming activity

lead a farmer to sell/lease land to domestic big landholders or

foreign direct investors12,

and migrate into cities? How then would the city infrastructure

bear the additional burden?

-

Production of

agricultural commodities for exports necessitates their smooth,

reliable and timely delivery to the markets. The development of such

infra structure amounts to land acquisition by the government in the

name of "public

purpose," but have adequate provisions been made for the

rehabilitation and resettlement of the displaced tribals?

-

What impact has

all this had on diversity in Indian agriculture? It has been

alleged that the introduction of monocultures exacerbates social

inequities by discriminating against small farmers who cannot afford

the necessary expensive inputs like fertilizer and pesticides.

Besides, the preservation of biodiversity is vital for local

populations because ecosystems suffering from a loss of biodiversity

end up losing their capacity to support the human populations

dependent upon them.

-

At the same

time, the impact on the environment cannot be ignored either. Is the

excessive use of chemical inputs not already resulting in massive

land degradation, soil erosion, siltation of reservoirs, local

climate changes, desertification and loss of land productivity?

-

What are the

implications of commercial agriculture on the larger issue of food

security -- for the nation, and for the individual?

-

How are the

issues of genetically modified crops going to play themselves out in

the national and international political arenas and what impact

would they have on the lives and livelihoods of the farmers

concerned?

None of these issues

is of a minor nature or simple in solution. The Project proposes to

examine the phenomenon of commercialization of agriculture in the

state of Andhra Pradesh that has most enthusiastically embraced

agricultural reforms, including power and water sector reforms that

have a bearing on agriculture. Yet, the state has also been in the

news in recent times for farmers committing suicides or selling vital

body organs to pay back loans taken for expensive agricultural

inputs. The Project endeavors to explore the linkages.

FOOTNOTES

1

It was founded by Walden Bello and Kamal Malhotra in 1995, and is

currently attached to Chulalongkorn University Social Research

Institute (CUSRI) in Bangkok, Thailand.

2

Also known as the Institute for Food and Development Policy, Food

First is an alternative policy think tank. Through research,

analysis, education and advocacy, it seeks to mobilize people to

take action to end injustices that cause ecological devastation and

hunger all over the world. The organization was founded by Frances

Moore Lappe and Joseph Collins about 25 years ago.

3

Center for Global Justice is an NGO that undertakes research,

advocacy and action to guarantee the economic, social, cultural,

civil and political human rights of marginalized sections of society

in Brazil.

4

NLC is the secretariat of a South African NGO network comprising of

eight affiliated land rights organizations actively working to

assist poor black rural people in their fight for land rights and

development assistance.

5

The Project defines land reform as reforms in land tenure, tenancy,

land distribution, and re-distribution, access to land, land-use

rights, land titling, land registries, land privatization and land

markets, each alone or in combination, and with or without

programmes to promote agricultural production or forest exploitation

use via credit, technical assistance, infrastructure development

etc.

6

Walter Fernandes, "Land,

Water and Air as Community Livelihood: Impact of Globalization",

Unpublished paper presented at Conference on "Ecology

and Theology", held in Bangalore, December 10-15, 2001.

7

Ibid.

8

Figures as found in India Rural Development Report brought

out by the National Institute for Rural Development, Hyderabad. The

Report itself is based on National Sample Survey data of 1999.

9

Robin Mearns,, "Access

to Land in Rural India", The World Bank Policy Research Working

Paper (2123), May 1999.

10

The World Bank's involvement in the green revolution began in 1964

when it sent a mission headed by Bernard Bell to India. The Bell

mission called for a devaluation of Indian

currency, liberalization of trade

controls and greater emphasis on chemical-intensive and

capital-intensive agriculture.

11

Figures as quoted by Vandana Shiva in an article on the

Environmental Consequences of Commercial Agriculture.

12

For further reading on this refer to report on the workshop,

"WTO/GATT

instruments and the Indian Farmer" organized by Focus on the

Global South -- India Programme during January 2001.

###

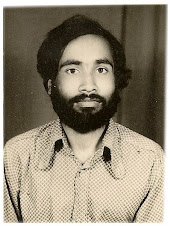

Following is a paper written by Admiral Vishnu Bhagwat. Admiral Vishnu Baghwat assumed charge of the Indian Navy, as the 15th Chief of Naval Staff, on 30 September 1996. Admiral Bhagwat has been a strong votary of Ambedkar & his Economic vision which has remained on the margins, as not much scholarship is available on that. This was a paper he presented in a seminar. Mr Vidyabhushan Rawat likes to share this with Atrocitynews readers. The views and opinion expressed are in individual capacity , Atrocitynews does not necessarily represents/endorce them in anyform. However Atrocitynews invites readers comments on this piece.

Dr Ambedkar descended the Indian skies like a meteor, lighting up the freedom movement with a viable economic vision and road map, charted a constitutional democracy which, as he often said, could take us to the revolutionary goal of equality , liberty and fraternity. This assessment is accepted by a large number of people. However, his economic ideology and mission have been buried in the sands of globalisation , privatization and 'reforms' by the ruling elite and even his self-proclaimed followers , who have joined hands in erecting stone and granite statues of the 'Revolutionary' whose thoughts not only sprang from the soil of the country but also its political ,economic and social realities ( It was buried even earlier by those who presented a confused and diffused ideology from various political platforms, and who buried his rational and scientific thinking ) .

If we really, deeply study his core ideas , ideology if you like , his central mission is spelt out in his drafts to the Constitution Drafting Committee of which he was the Chairman ,1947-49 . Dr Ambedkar finally emerged as the main 'Architect' of this most vital document that lays down the framework of the Republic and its social , political and economic objectives , which is a manifesto of those who struggled for India's freedom against foreign capital , foreign rule and local dominant , economic and caste interests . The Constitution is above the Supreme Court , the Lok Sabha , the Prime Minister and the Executive and was intended to be its guiding star , its Dhruva tara. How much we have deviated from the Constitution's Directive , its soul the Directive Principles which are mandatory for any Government in office is an issue which is for all of us to assess. . If this is tested by the ground reality of the condition of the exploited classes , the denial of equality of opportunity , of education, of the very right to life , to work, and economic policies which have made the preamble of the Constitution a paper promise in the hands of the exploiting class who have arrogated to themselves a near total monopoly of resources , unprecedented and growing concentration of wealth that make a mockery of the direction 'for the common good'.

First of all let us try to forge a common understanding of how 'Ambedkar thought' evolved ? Is it possible to flag mark Dr Ambedkar's tortuous yet blazing journey . Dr Ambedkar chose his own methodology to educate and inform himself . It is true that cataclysmic events took place in the journey of his life…the 1917 October Proletarian Revolution in Russia, which to begin with placed power in the hands of the workers and peasants , the toiling and hitherto exploited class . In my understanding , though he may not have explicitly stated so in his revolutionary call in Manmad in 1938 , that was the central idea of his declaration of the three principles at the workers conference to which we will come as we discuss further . Then came the 'Great Economic Depression' of 1929 , with its devastation , hunger and unemployment , which not only burnt and singed the people in the United States but also in Europe . The Capitalist classes across the industrialized countries speedily funded Fascist groups , to further disposses and divert the working class . This was spread through fear and propaganda , promising them the mirage of nationalism , discipline, conquests and full employment , at the same time breaking their organizations , enslaving them in factories , mines and plants jointly owned by global 'finance capital' , including by American corporations and British capitalists , through the 1930s , as now brought to light , through the period of the Second World War ,via a commonly owned and set up Banking system, while the soldiers were killed and maimed as cannon fodder on military fronts all over the world in Europe , the Soviet Union , North Africa and Asia . Dr Ambedkar by now a champion of Dalit rights also clearly saw that Dalit emancipation could only be achieved through a broad united front of all the exploited classes . Dr Ambedkar had already defined a Dalit as 'one who struggles' ( for democratic rights ). His definition was, therefore, categorically inclusive of all individuals and groups who were naturally bonded , engaged in the common struggle, of the exploited classes.

Dr Ambedkar had through his definitive works , beginning in 1917 with his outstanding doctoral dissertation at the Colombia University, the "National Dividend of India" , essentially on the transfer of wealth and surpluses from India to Imperial Britain , laid bare the huge colonial (looting ) enterprise on which Britain's industrialization was founded . There is another work , that of RC Dutt , covering this path breaking subject ; which dared to expose to bare bones , through facts , figures , official documents how Britain , later called 'Great Britain', established and executed the great parasitical enterprise , called British India . Dadabhai Naoroji whom Dr Ambedkar greatly respected also spoke and wrote on the rapacious transfer of surpluses from India to England .This thought process , bold and courageous in the extreme, shook those little social clubs who were petitioning the Sarkar for some concessions in entrance to the British Indian Army through the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst and the ICS quota for Indians . Historically , it was quite a coincidence that Gandhi's own experiences in South Africa of racial discrimination and apartheid , brought him to India and start transforming the Congress into a mass organization of peasants , workers and all the toiling masses within the limitations of the social setup in the country. Not content with his monumental work Dr Ambedkar finished writing his " Small Holdings in India and their Remedies in 1917." We cannot but infer that Mahatma Jyotiba Phule's "Kisan Che Kode" inspired him and stoked his passion to try and expose, and later struggle , by throwing in his lot with those classes subjected to extreme social , political and economic exploitation .

Academically and to further consolidate his grasp of Public Finance was published in 1921, he worked on and published "Provincial Decentralisation of Imperial Finance in British India , the Problem of the Rupee ( the issues of Silver and Gold Standards ) in 1923 , the Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India 1925. Let us pause for a moment and reflect on the boundless energy , the diligence and perseverance , the prodigious output of the Man. No economist in India has produced such monumental , vital and relevant works as Bhimrao Ambedkar did in those nine years 1916-25. Undoubtedly these studies gave him an incomparable advantage over his contemporaries . He may have surpassed his contribution as a Law Minister after 1950 in the field of public finance if he had been Finance Minister ; but Finance Ministers in the existing system have to be conservatives not revolutionaries , who may upset the 'apple cart' !

Dr Ambedkar had emerged as ,by far the most erudite and scholarly economist on the sub-continent. His alert , incisive and sensitive mind was now setting up his own compass for the struggles ahead as he walked tall in the thirties. The Great Depression of 1929 –33 shook the whole world and its epicenter was in the United States and Europe , the foremost capitalist systems, where he had spent his period of study and observation . Capitalism's exploitative chain had broken down and was engulfed by a serious crisis ; it was replaced by Fascism , i.e the rule by private Corporations in partnership with the ruling elite controlling the State apparatus. Dr Ambedkar was perceptive enough to grasp the significance of slave labour being used by the Corporations . While he had pre-occupations with the Round Table Conference, the Poona Pact , the Government of India Act 1935 , the provincial elections and Separate electorates ; he was deeply distressed by the exploitation , impoverishment, daily humiliation and denial of human rights to the exploited classes and the Dalits in the social mileu of the backward , feudal , arch conservative society that had evolved in the country of his birth . This evolution was not an accident . Michiavellian state craft in combination with parasitical economic production relations and a cruel , ritual order was used as a means to enslave the people who built India . Another economist in Ancient India had seen through it all – Chanakya who led a revolt of the slaves and helped install a Shudra dynasty , the Mauryas , which held sway over most of India until it was done out by a regrouping of the wealthy and the propertied , expropriating classes . The people who toiled in the fields to produce food, the bundkars who wove clothes and fabrics , the artisans who made tools with their hands , household items and the most exquisite articles with precious stones and alloy metals , the people who built homes , palaces and monuments, the leather workers who made shoes , saddles for the army cavalry and without whose services society would not exist and flourish , were all continuously being cheated , looted through expropriation of the surpluses that they created by their sweat, blood and sacrifices. The Manu Smriti , a fraudulent , adharmic manufacture of diseased minds of some elements of the priestly class who had prostituted themselves to the exploiting , ruling class to lay a spider's web of fear , intimidation and an unimaginably, cruel and despotic social order based on all that is ignoble , unjust and unequal , in direct opposition to the Dharma that many great minds, specially Gautam Buddha , and those who guided Indian society had laid down. The nectar of Dr Ambedkar's perceptions can be gauged by a better effort at understanding the essence of his writings and speeches , through his life and the stands he took, some necessarily with compromises, underpinned by his deep understanding of how the exploitative chain and the process of accumulation of surplus works and creates an overwhelming majority of serfs and slaves as an economic underclass leading a dehumanizing animal like existence , outside the boundaries of the proper village or bustee and in slums and ghettoes in the cities and towns as outcastes , untouchables and sub humans or'unter-menschens'. Others , so called born into higher castes have also been forced into this large mass of labor, of unceasing toil , of carrying the load on their backs and pulling the 'thela', since then with the rise of modern capitalism.

Dr Ambedkar had decided to carry out the struggle on two tracks ; to destroy the oppressive social order and to bring about an equitable , non –capitalist economic restructuring through mass awakening , reform and democratic movements , as he believed that real economic democracy was a means to transform a nation to a just order . He said 'the struggle for economic justice was as important as the struggle for social justice' . Why has this central idea and central mission of Dr Ambedkar's life been forgotten and his core ideas and philosophy on the struggle for economic justice , suppressed by various big leaders and movements in all corners of the country is a question of fundamental importance ? This needs to be urgently corrected if we have to move forward.

We have seen how the Sanghis , who are essentially adherents of the Manu Smriti order, infiltrated and subverted the Congress Party , pre and post Independence , camouflage the core issue of economic justice while rationalizing 'social justice' to fool the people, assassinated Gandhi for opposing the domination of British finance capital in India which devastated the Indian economy . This class opposed the mild dose of reform for the Hindu society , the Hindu Code Bill and engineering riots and pogroms and spreading division and violence through their well-oiled Goebellsian propaganda machinery , all funded by the corporate class . What of ourselves why is it that we too have deviated from the central thread that runs through the mission of Dr Ambedkar's life ?

As we have seen Dr Ambedkar through his logic , reasoning and scientific rationale , backed by a deep and real understanding of theoretical and applied economics, charted a path for all Indians, for the Dalits who he defined as ALL those engaged in the ' Struggle' for emancipation from the bondage of the exploitative order , through centuries of feudal and capitalist domination .

It is no surprise , therefore, that he set his precepts into practise by mobilizing and leading the march for temple entry at Mahad , to be shortly followed by his stirring address at the Independent Labour Party Conference at Manmad in 1938. This was a continuity of the calls of TukaRam , Shahuji Maharaj , Jyoitaba Phule , only set in the contemporary context and sharply focussing on the struggle for economic justice that lay ahead . These ideas he later introduced in his draft submissions for the Constitution and the final form of the Constitution, of which he was the principal architect. ( Imagine if the Constitution of India had been drafted in 2004 ,and indeed the attempt to 'reform' the Constitution by the Sangh Parivar had succeeded in 1999-2000 , what kind of a Constitution would we have today ! )

Manmad 1938, the GIP Railway Dalit Mazdoor Conference, ( caste discrimination was practiced in the railways and the textile mills , with the lower and lesser paid jobs going to the Dalits ; while clean and weaving jobs went to the 'other' workers ) , was a defining moment in Dalit struggle , an inflexion point, a turning point, that focuses both on the contemporary reality and a guiding star for the times ahead. Dr Ambedkar places before all, this foundation of his beliefs , convictions and the path that leads to the future , that the Dalits in a common united front to be forged with all the exploited classes , to achieve the goal of social and economic justice in an egalitarian society and real democracy thus :