Resistance against persecution of Bengali Refugees in India

Indian Holocaust My Father`s Life and Time - ELEVEN

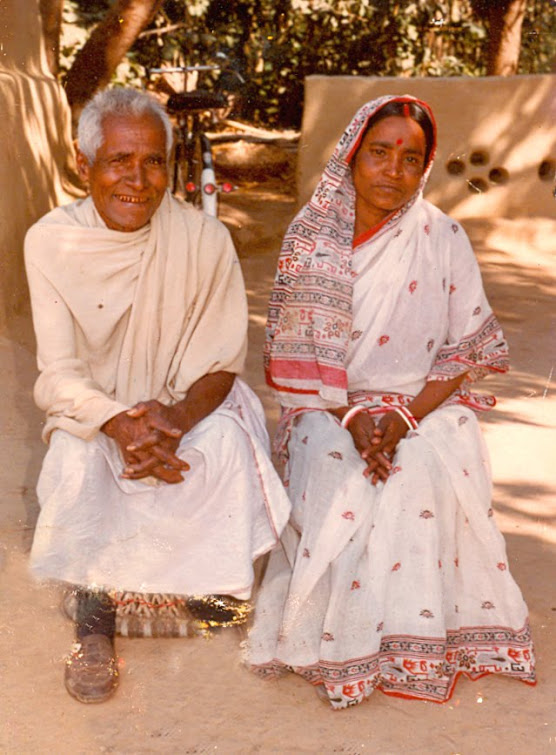

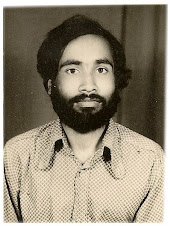

Palash Biswas

They are partition victims and were welcome by the nation in the greatest population transfer in the history.The partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 was followed by the forced uprooting of an estimated 18 million people. The minority communities in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) who were uprooted and forced to seek shelter in the Indian province of West Bengal.Jawahar Lal Nehru and his government failed to stop the carnage of minorities accross the border. Hence, the East Bengal partition victims, stripped of citizenship, human and civil rights, dislodged from history and geography and deprived of mother language and employment have to pay the price after almost sixty years of Indian Independence.

They are being persecuted in every part of India just because they speak in Bengali and ninty percent of them are dalits. Speaking in Bengali has become the only criteria to identify Bangladeshi nationals outside Bengal. Because the partition victim Bengalies, even settled in foties and fifties belong to underclasses, they are unable to protect themselves agnaist atrocities including deportation drive.

Hopefully, resistance agnaist persecution of East Bengal refugees is getting momentum. In Uttaranchal and Orrissa, the local people, political parties and media stand united with the refugees. Uttaranchal refugees have launched nonstop mass movement since they were denied Indian citizenship in 2003 by then Bjp government. The chief minister of Uttaranchal Narayan Dutta Tiwari raised the issue thrice in the parliament. In Orrissa, a farther step ahead the agitation is led by the Utkal Bangiay Surakshya Samiti. Left MPs belonging to cpim and forward block visited refugee areas in Uttaranchal and Orrissa. Left front chairman in West Bengal, comrade Biman Bose visted village to village in Uttaranchal. Basudev Acharya, cpim MP has visited Kendarapara on last 10 th October where 1575 Bengali refugees have been served quit India notice. They could not be deported because the people of Orrissa, political parties and media support them. But the notice is still live. Orrissa government of Bjp Bjd combine has alredy managed 21 Bengali refugees settled in Navrangpur. Kendra Para was targeted as second attempt which failed. In retaliation , the Orrissa government stopped no less than two hundred refugee children to sit in high school examination. Birth certificates are being denied to newborn babies. BPL card, ration Card, PAN, etc have been stalled. Names of refugees in the voters` list have been deleted enmasse.

Mulnivasi Bamcef is leading the movement to save the dalit refugees in Maharashtra, where 250 Bengali refugees have been arrested and released after paying ten thousand ruppees each and submitting a personal bond to prove their Indian citizenship with adequate documents within one month in Bhandara district. All Maharashtra DMs have notified the resttled partition victim Bengali refugees to submint documents to prove Indian citizenship within a month.

In Kolkata, on Friday, 27th october a seminar was organised by SAHMARMEE and Dalit Samanyaya Samiti to protest the persecution of Bengali Refugees in different parts of India. The seminar was presided over by the ex Vice Chancellor of Kalayani University and now a cpim Loksabha member Dr. Basudev Barman. Sahmarmmee general secretary Dr Nitish Biswas, deputy registrar of Calcutta university introduced the topic and gave garphic details of persecution of Bengali refugees on grounds like citizenship, human rights , civil rights, reservation, employment and mother language.

All India forward Block general secretary and rajyasabha member Debbrata Biswas was the main speaker and he gave the graphic details statewise. He Said, outside Bengal the refugees are being persecuted, deported, put behind bars and descriminated just they speak in Bengali. He also presented his experience of visits in refugee colonies in different parts of india. He said , refugees may not survive in Uttaranchal, UP, MP, Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgargh, Assam, Maharashtra, Gujrat, Andhra, Tamilnadu, Rajsthanand elsewhere in these circumstances. He called for a nonstop left movemenyt in parliament and outside parliament to protect the Dalit Bengali refugees.

Ex education minister of West Bengal kanti Biswas, acpim MLA and ideologue supported the plea. He further elaboarated the issue.

Convenor of All India Refugee Coordination committee, Dr Subodh Biswas came fro Nagpur and reported the situation and updates.

JM Bhowmic and Ujjwal Biswas from dacca also particiapted in the seminar.

Indian nationalist leadership chose to hold on to this Muslim-majority state to prove that minorities could thrive in a plural, secular polity. But the government of India could not secure the saftey of Hindus and other minorities in erswhile East Pakistan and now in bangladesh either politically ordiplomatically. The situation is that the refugee influx from Bangladesh has never to stop. Any internal turmoil In Bangldesh creates waves of exodus. It is happening once againas the ruling classes fight on streets doggedly to have the riegn of power, the security and safety of minorities are once again at the stake. Government of India may not help it. West Bengal chief minister is concerned and a high alert is declare by Border Security Forces in border areas of West Bengal. Is this a solution?

In fact, a delegation of Hindu minorities recently met The Indian High Commissioner in Dacca and demanded that either the two corore Hindus still sustaing themselves in Bangladesh, should be allowed to cross over Indian border and be granted Indian citizenship enmasses - or India should ensure the saftey of life , property and respect for the Hindus there.

Population exchanges

Massive population exchanges occurred between the two newly-formed nations in the months immediately following Partition. Once the lines were established, about 14.5 million people crossed the borders to what they hoped was the relative safety of religious majority. Based on 1951 Census of displaced persons, 7.226 million Muslims went to Pakistan from India while 7.249 million Hindus and Sikhs moved to India from Pakistan immediately after partition. About 11.2 million or 78% of the population transfer took place in the west, with Punjab accounting for most of it; 5.3 million Muslims moved from India to West Punjab in Pakistan, 3.4 million Hindus and Sikhs moved from Pakistan to East Punjab in India; elsewhere in the west 1.2 million moved in each direction to and from Sind. The initial population transfer on the east involved 3.5 million Hindus moving from East Bengal to India and only 0.7 million Muslims moving the other way. [citation needed]

Massive violence and slaughter occurred on both sides of the border as the newly formed governments were completely unequipped to deal with migrations of such staggering magnitude. Estimates of the number of deaths vary from two hundred thousand to a million.[1]

[edit] The present-day religious demographics of India proper and former East and West Pakistan

Despite the huge migrations during and after Partition, secular and federal India is still home to the third largest Muslim population in the world (after Indonesia and Pakistan). The current estimates for India (see Demographics of India) are as shown below. Islamic Pakistan, the former West Pakistan, has a smaller minority population. Its religious distribution is below (see Demographics of Pakistan). As for Bangladesh, the former East Pakistan, the non-Muslim share is somewhat larger (see Demographics of Bangladesh):

India (2005 Est. 1,080 million vs. 1951 Census 361 million)

81.69% Hindu (839 million)

12.20% Muslims (135 million)

2.32% Christians (25 million)

1.85% Sikhs (20 million)

1.94% Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and others (21 million)

Pakistan (2005 Est. 162 vs. 1951 Census 34 million)

98.0% Muslims (159 million)

1.0% Christians (1.62 million)

1.0% Hindus, Sikhs and others (1.62 million)

Bangladesh (2005 Est. 144 vs. 1951 Census 42 million)

86% Muslims (124 million)

13% Hindus (18 million)

1% Christians, Buddhists and Animists (1.44 million)

We Indians, perhaps, have forgot the hard facts.

Gyanesh Kudaisya in his research article`DIVIDED LANDSCAPES, FRAGMENTED IDENTITIES: EAST BENGAL REFUGEES AND THEIR REHABILITATION IN INDIA, 1947–79 ‘ considers the responses of Indian federal and provincial governments to the challenge of refugee rehabilitation. A study is made of the Dandakaranya scheme which was undertaken after 1958 to resettle the refugees by colonising forest land: the project was sited in a peninsular region marked by plateaus and hill ranges which the refugees, originally from the riverine and deltaic landscape of Bengal, found hard to accept. Despite substantial official rehabilitation efforts, the refugees demanded to be resettled back in their "natural habitat" of Indian Bengal. However, this was resisted by the state. Notwithstanding this opposition, a large number of East Bengal refugees moved back into regions which formed a part of erstwhile undivided Bengal where, without any government aid and planning, they colonised lands and created their own habitats. Many preferred to become squatters in the slums that sprawled in and around Calcutta. The complex interplay of identity and landscape, of dependence and self-help, that informed the choices which the refugees made in rebuilding their lives is analysed in the paper.

This is an abridged version of an essay published in the volume, Partition of Memory, ed., Suvir Kaul, Permanent Black, 2001. Thanks are to the publisher and editor of the volume.

Rights or Charity?

Relief and Rehabilitation in West Bengal

In the half-century since India was partitioned, more than twenty-five million refugees have crossed the frontier between East Pakistan and the state of West Bengal in India. The migration out of East Bengal, and the way the refugees were received by India was very different from West Pakistan. Unlike those from the west, the refugees from the east did not flood into India in one huge wave; they came sometimes in surges but often in trickles over five decades of independence.

The elemental violence of partition in the Punjab explains why millions crossed its plains in 1947. By contrast, the, causes of the much larger migration out o East Bengal over a longer time span are more complex That migration was caused by many different factors minorities found their fortunes rapidly declining as avenues of advancement and livelihood were foreclosed; they also experienced social harassment, whether open and fierce or covert and subtle, usually set against a backcloth o communal hostility which, in Hindu perception at least, was sometimes banked but always burning. Another critical factor was the ups and downs in India's relationship with Pakistan which powerfully influenced why and when the refugees fled to West Bengal.

Given this context, the strikingly different way in which the Government of India viewed the refugee problem in the east and in the west is not altogether surprising. The crisis in Punjab was seen as a national emergency, to be tackled on a war footing. From the start, government accepted that a transfer of population with Pakistan was inevitable and irreversible. So it readily committed itself to the view that refugees from the west would have to be fully and permanently rehabilitated. It also quickly decided that Muslim evacuee property would be given to the refugees as the cornerstone of its programmes of rehabilitating them.

The influx of refugees into Bengal, on the other hand, was seen in a very different light. In Nehru's view, and this was typical of the Congress High Command, conditions in East Bengal did not constitute a grave danger to its Hindu minorities. Delhi regarded their flight as the product of imaginary fears and baseless rumours, rather than the consequence of palpable threats to life, limb and property. Well after it had begun, Nehru continued to believe that the exodus could be halted, even reversed, provided government in Dacca could be persuaded to deploy 'psychological measures' to restore confidence among the Hindu minorities. The Inter-Dominion Agreement of April 1948 was designed, Canute-like, to prevent the tide coming in. In the meantime, government gave relief to refugees from East Bengal as a stop-gap measure since permanent rehabilitation was thought unnecessary; indeed it was to be discouraged.

So it set itself against the redistribution of the property of Muslim evacuees from Bengal to incoming Hindu refugees; the policy was to hold it in trust for the Muslims until they too returned home. The official line was grounded in the belief that Bengali refugees crossing the border in either direction could, and indeed should, be persuaded to return home. Even after the number of refugees in Bengal had outstripped those from Punjab, such relief and rehabilitation measures as government put into place still bore the mark of its unwillingness to accept that the problem would not simply go away.

This was what led the refugees to demand that government give them what they regarded as their 'rights'. Their movement of protest embroiled refugees and government in a bitter, long-drawn-out battle over what legitimately could be expected from the state. The nub of the matter was quite simple: did the refugees have rights to relief and permanent rehabilitation, and did government have a responsibility to satisfy these rights? In examining what divided the government and the refugees, I wish to assess how far apart the positions of the refugees and the government were and how different the premises on which they were based. In the process I shall try to locate the role that marginal groups, notably the refugees, have played in creating notions of legitimacy and citizenship that came to challenge India's new orthodoxies.

The construction of relief as charity

Campaigns by refugees against government diktat were a persistent feature of political life in West Bengal well into the nineteen?sixties, but the formative period coincided with the initial wave of migration between 1947 and 1950. The issues began to crystallise after the Government of West Bengal decided td deny relief to 'able-bodied males' and to phase out relief camps. As soon as refugees demanded a say in their rehabilitation, the battle lines were drawn. Stopping free relief to able-bodied males was the first of a series of measures to limit government's liability towards the refugees. The essence of the policy was to whittle down, by one device or another, the numbers eligible for help from the state. By November 1948, as soon as the surge in migration caused largely by events in Hyderabad began to tail off, government was quick to claim that the worst was over; some officials, adding their two-annas' bit, even argued that the lure of handouts was itself attracting migrants.

In late 1948, the government began to put a new and harsher policy into place. On 25 November 1948, Cakift announced that only refugees, defined as persons ordinarily resident in East Bengal who entered West Bengal between 1 June 1947 and 25 June 1948, "on account of civil disturbances or fear of such disturbances or the partition of India, would be entitled to relief and rehabilitation. A second order in December 1948 declared that no more refugees would be registered after 15 January 1949, further cutting back the official definition of a "refugee". A month earlier, on 22 November 1948, the Government of West Bengal had decreed that no 'able-bodied male immigrant' capable of earning a living would be given gratuitous relief for himself or his family for more than a week. After that, relief would be conditional only against works.

It was all very well for government to offer relief against works, but there weren't any such "works" and government gave no assurance that it would create them. Instead, the official line was that the immigrant "through his own effort" must find suitable work. Male refugees capable of working had somehow instantly and miraculously to find for themselves jobs, sufficiently remunerative to feed, clothe and house themselves and their families, within seven days of crossing the border. Furthermore, government urged refugees go anywhere in West Bengal except Calcutta and its suburbs, where casual employment was most easily to be found.

To begin with, government had allowed camp officers discretion to make exceptions in those cases where they felt that free relief (or "doles", as they were called in terminology unattractively reminiscent of the Poor Law) was "essential for preservation of life". Put bluntly, government realised that it would not look good if people starved to death in its camps. Two months later, however, in the wake of refugee hunger strikes against its directives, it hardened its heart.

On 15 February 1949 the new national government decreed that "such able bodied immigrants as do not accept offers of employment or rehabilitation facilities without justification should be denied gratuitous relief even if they may be found starving" (Memo No. 800 (14) R.R., Secretary, Relief and Rehabilitation Department, Government of West Bengal, to all District Officers, 15 February 1949; emphasis added). This decision was reiterated towards the end of March 1949.

In a directive aimed at "soft" camp superintendents suspected of being susceptible to pressures from refugees, it laid down that free relief must not be given to anyone merely because he was found starving once, the underlying principle being that an able bodied male must earn his own living, and should not be made to feel, under any circumstances, that he can at any time be a charge on the state" (Memo No. 1745 (10) R.R.,/18R-18/49, from the Secretary, Relief and Rehabilitation Department, Government of West Bengal, to all District Officers, dated 29 March 1949).

In July 1949, Calcutta announced that all relief camps in West Bengal must be closed down by 31 October 1949, and ordered that rehabilitation of the inmates be completed by that date. From now on it would only rehabilitate those few persons it chose to define as refugees, Refugees should expect no further relief and would be entitled only to whatever crumbs by way of rehabilitation government decided to offer them. This was the first in a series of official announcements by which it was made unequivocally clear that refugees had no choice in the matter. They had to take what was offered or get nothing at all.

What government set out to do, at least in the prospectus, was to encourage refugees to be self employed. Categorised by their social background and training, refugees were to be offered soft loans of varying amounts to enable them to buy appropriate equipment, tools or supplies in order to set themselves up as entrepreneurs. Those who felt they had neither the training nor the talent for entrepreneurship but wanted 'proper jobs' instead, those who preferred to stay on in camps or 'deserted' 'rehabilitation colonies' were given no choice. They had to do as they were told or lose all claim to the meagre benefits on offer.

These directives give an insight into the government's view of its responsibilities towards the refugees. By attempting repeatedly to restrict the definition of who could claim to be a 'refugee', government showed that it had to accept, however grudgingly, that it could not altogether avoid responsibility for those displaced by partition. The fine platitude, frequently voiced in the documents of the Rehabilitation Department, was that "to succour and rehabilitate the victims of communal passion [was] an obligation the country [was] solemnly pledged to honour". (Quotation from Bhaskar Rao, The Story of Rehabilitation, p. 229)

In practice, however, government strove to limit its liability by cutting its definition of the term 'refugee' to the bone. A refugee, Calcutta declared, was a person who had migrated before the end of June 1948 and registered himself as such before January 1949 - a key device by which government sought to achieve this objective to limit its definition of "partition" itself. By its edict, partition was defined as occurrences, which began in June 1947 (or six months earlier in December 1946 if the refugee had happened to live in Noakhali or Tippera) and abruptly came to an end one year later in June 1948. That partition was a process which began in 1947, but whose impact continued to unfold long after June 1948 was obvious to everyone outside the Writers Building. But by adopting these myopic, self-serving definitions, Bengal's new rulers lost the ability to anticipate and effectively react to the ongoing problems caused by partition. Not surprisingly, they were caught off guard by each new crisis.

In a similar vein, 'the government strictly defined what could be deemed to be the effects of partition. According to its taxonomy, "civil disturbances" alone -that is communal violence or discrimination against minorities - were accepted as genuine "effects" of partition. Only those who had fled communal violence were regarded as "genuine" victims of partition and therefore as refugees entitled to protection from the Indian state.

But economic hardship in East Bengal - wfiere famine stalked the land and where food cost much more than anywhere else in India - was not accepted as a consequence of partition. It may have been obvious to others that partition had directly and disastrously affected the livelihoods of millions of people, Hindus and Muslims, in both Bengals, but migrants tossed across borders by the pitchfork of necessity were not deemed by government to be genuine victims of partition or as "true" refugees.

So it followed that they were not in any sense the responsibility of the Indian state. This helps to explain why the Government of India treated the refugees from Punjab, where communal violence came close to being genocide, so differently from the refugees from East Bengal, where the violence was never remotely on this scale. The Prime Minister justified to the Chief Minister of West Bengal the striking difference in expenditure per capita on refugees in the West and East by arguing that while 'there was something elemental' about the situation in West Pakistan, "where practically all Hindus and Sikhs have been driven out", whereas in the East it was more gradual, and many Hindus had been able to remain. (Jawaharlal Nehru to B.C. Roy, 2 December 1949, cited in Saroj Chakrabarti, With Dr. B.C. Roy, p. 143).

The official definition of the refugee as victim deserves closer scrutiny, as it provides another key to assess the tenuous morality behind government's attitude. Only bona-fide victims were entitled to relief and rehabilitation. To be eligible for relief, the victims had to register themselves. In December 1948, when government made public its decision to shut down registration offices by 15 January 1949, it justified the edict by arguing that refugees who were "genuinely interested" had been given "ample time" to register (Relief and Rehabilitation Department, Government of West Bengal, Memo, 20 December 1948, in GB IB 1838/48).

This introduced a new refinement to the horrors of partition - a "desperation index" in the procedures by which a refugee was prevented from claiming benefits. If a refugee was truly desperate, government argued, he would have found his way to a registration office by mid-January 1949. It he didn't, that was the proof positive that the person claiming refugee status could not have been sufficiently desperate to require relief. In this way, government at a stroke cut down a huge problem to a size it felt it could handle.

This had far-reaching implications for the way in which government responded to 'refugee demands once they came to be voiced in an organised way. By definition, victims are not commanders of their own destiny; victims are not agents. Rather they are the "innocent", passive, objects of persecution, casualties of fate. Significantly, the state's favourite euphemism for refugees was "displaced persons", with connotations of innocent victims dislocated by events in whose shaping they had played no part. This helped government to justify treating the refugees from West Pakistan and East Bengal with such an uneven hand.

Nehru's point was that the Punjabis had been driven out from their homes. Bengalis, by contrast, by migrating in fits and starts, proved that they had the option of staying or of leaving. According to the official line, a true refugee or victim had no choice and was not a free agent. He could therefore not be expected to exercise volition, or have any choice over how or when he was to leave the country he lived, and where, when and how he sought refuge in the country he now lived in. By defining refugees in this way, government could argue that it helped refugees not because of any obligation but voluntarily, out of the goodness of its heart. In effect, what the refugee received was charity. Since the recipient of charity has no right over how much or what he is given, so too the refugee had no moral right to relief, nor any say over what was doled out to him.

This construction of relief and rehabilitation as charity is seen most explicitly when government decided at a stroke to stop "doles" for able-bodied males and to shut down its camps. In its defence, government insisted that doles were simply a form of official charity. If able-bodied men accepted these handouts, this would erode their moral bier and get them accustomed to a culture of dependency. "Living on the permanent charity of doles" would, it was argued, make them "sink into a state of hopeless demoralisation". Camps, likewise, were seen as "symbols of permanent dependence" (The Story of Rehabilitation, p. 160).

So while the refugees survived on the barest rations, government was able to represent its relief to the refugees as "charity" (and to congratulate itself for being so charitable), and at the same time reprimand the refugees for daring to expect its charity. This double-edged policy of charity so dominated official thinking that it suggests that it was the very touchstone of rehabilitation policy. In official pronouncements, the notion that charity bred a demoralising "dependence" inconsistent with manly self-respect was seen as an obvious truth, alluding to what was considered as common currency of Indian culture.

But was this view of charity the generally accepted one in a social milieu where dana, dakshina and bhjksha had long been vital elements of religious and social life, and where the renouncer who lived on alms was venerated at least as much as the house-holder? It is by no means clear that it was. By all accounts, this view was of recent origin, even in Europe, where "in the old days, -the beggar who knocked at the rich man's door was regarded as a messenger from God, and might even be Christ in disguise". By the late eighteenth century, accepting charity had already begun to attract social odium; a century later, the wheel had come full circle and charity was seen as "injuring" those it was intended to aid. Likewise it was only in industrial Europe that 'dependency' came to denote a stigmatised condition, appropriate only for women, children and the infirm.

When England put its New Poor Law onto the statute book in 1834, this attitude informed the amendment which aimed broth to deter the poor from resorting to public assistance and to stigmatise those who did. By the early twentieth century, dependency had come to be taken as a mark of debility of character rather than a function of poverty. So an able-bodied male who came to be dependent was seen as the epitome of the 'undeserving poor', since it was not poverty, but a man's lack of self-respect, that caused his dependence. And because it was only acceptable for women and children to be dependent, an able-bodied dependent man was seen to have the perceived attributes of women and children: weakness, idleness, passivity and irresponsibility.

These imported European attitudes towards charity and dependency were deployed with such great effect by India's policy-makers because in their passage to Bengal, they assumed highly charged local inflections and particular resonances of their own. In one of the deeper ironies of Bengal's modern history, this way of thinking happened to fit neatly with a pre-existing tradition among its colonial masters about the flawed character of the Bengali Hindu male. In the nineteenth century, British officials had conventionally regarded physical weakness and lack of vigour, lethargy, effeminacy and an absence of moral backbone as the very essence of the Bengali babu's being. By the mid-twentieth century, the Bengali Hindu male was thus seen by his imperial critic as a deplorable combination of the worst feminine and childish qualities.

Writing on rehabilitation by officers in Delhi and Calcutta unconsciously aped the prejudices of their erstwhile masters, thus bringing together two borrowed traditions-one from Europe and the other from colonial India's recent past - to produce a new and potent stereotype of the Bengali refugee. This characterisation was drawn in counter-point an equally hackneyed, but far more flattering, picture of the Punjabi refugee, whose 'toughness ... sturdy sense of self-reliance... [and] pride' never let them 'submit to the indignity of living on doles and charity'.

The Punjabi refugee, heir of the material races who were the darlings of the post-Mutiny Raj, was thus held up by independent Indian officialdom as the model of the 'deserving poor'. (The outrageousness of this statement is apparent given that Government allocated many thousand acres of land to the Punjabis, disbursed Rs 11 million among them for the purchase of livestock, and a gave them a further Rs 44 million in grants, loans and advances).

The contrast drawn by the officials between the Punjabi and the Bengali refugee could hardly have been sharper. The "character of the refugees themselves" was blamed for the failings of the rehabilitation effort in West Bengal. The official view was that his very disposition rendered the Bengali male refugee prone to fall into a state f dependency and therefore incapable of breaking out of it. Whereas "in the West, the refugee matched government efforts on his behalf with an overwhelming passion to be absorbed into the normal routine of living", in Bengal, "the government had to supply the initiative as well as the motive power. To overcome the apathy, even the sullenness, of the displaced person was itself no small task. It called for patience and tact, endless sympathy joined to occasional firmness..."

Here, the thesis brought together two different lines f argument. The first was that their qualities of character included a psychological dependency amongst Bengali ales, which rendered them incapable of making rational decisions for themselves. Because they were dependent, any judgment of their own about themselves and their lives and times had no value: it was as feeble and untrustworthy s the judgment of women and children.

The second line of argument, again borrowed from the vocabulary of the Raj, was that the state's relation to this dross of humankind was that of, surrogate patar families or benevolent despot. Because the refugees had placed themselves in its care, government had a duty to decide what was best for them. Government saw itself as standing in for the male breadwinner in relation to these unfortunates and therefore entitled to assert all the moral authority over them that a male breadwinner enjoys over his dependants.

Yet the refugees never made an issue of these contradictions. One reason might be that the impact of both constructions on their rights tended to be much the same in practice. If refugees were to be seen as dependent members of the national family, they could claim rights to maintenance only by virtue of their dependent status, and as dependants they were denied any other rights. If they were represented as recipients of voluntary charity, they had no claims whatever over the source of the charity. Indeed the very fact that they took charity showed them, in the official view, to be so 'psychologically dependent' that they were not fit to determine their own destinies.

Saturday, September 19, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment