F

rom his hospital bed in

Bangladesh's smoggy capital,

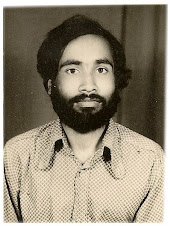

Dhaka, photographer Firoz

Chowdhury tries to explain why he

won't file any charges against the

men who beat him up the day before.

14 Spring | Summer 2004

Culture of Violence

In a country marred by political corruption,

Bangladesh's journalists suffer for telling the truth.

By Abi Wright

"It's too dangerous. They are carrying

arms. It's too risky for me."

Chowdhury, the chief photographer for the country's most popular

daily, Prothom Alo, has 13 years' professional experience and covers the

politically violent demonstrations

and strikes that frequently erupt on

the streets of Dhaka. On March 3, he

was beaten in the chest, back, shoulders, and legs by several members

of the ruling Bangladesh Nationalist

Party's (BNP) student wing, the

Jatiyatabadi Chhatra Dal (JCD), while

covering a student protest on the

Dhaka University campus.

Bangladesh, as Chowdhury can

attest, is a place where crime, poliRiot police detain a Dhaka University student during a demonstration on March 3, 2004. Thousands of students

had gathered to protest a recent knife attack on a professor.

AP/Pavel Rahman

Abi Wright is CPJ's Asia program coordinator. The reporting in this story is based

on a mission Wright and CPJ Executive Director Ann Cooper conducted to

Bangladesh in March 2004 with Iqbal Athas, defense correspondent for Sri

Lanka's The Sunday Times, and Andreas Harsono, managing editor of Indonesia's

Pantau magazine.Dangerous Assignments 15

tics, and violence all cross paths,

making independent journalism in

this country of 146 million people a

very dangerous profession. Political

officials routinely punish journalists

who expose corruption by ordering

political activist henchmen to beat

them. In addition, a highly polarized

political climate divides the country—and even journalists themselves—compounding the challenges

they face.

For now, those challenges are

unclear for Chowdhury as he grapples with the larger implications of

his attack. He is in pain, and he

speaks quietly as he describes how

the students' peaceful demonstration against a recent knife attack on

a professor turned violent after JCD

activists began forcibly breaking up

the crowd. Chowdhury's last photos

before the JCD members turned on

him show a young woman being

beaten by police and a JCD activist

kicking a group of protesters.

When they saw Chowdhury photographing them, the JCD members

grabbed his digital camera and

smashed it before beating him.

Police and JCD leaders stood by and

watched, according to Chowdhury.

Several other journalists covering

the protests were also beaten that

day by JCD members and police.

This was not the first time

Chowdhury had suffered violence at

the hands of political activists. He

says that what happened to him was

a "normal and regular occurrence"

for the press, and that JCD members

at Dhaka University punched him in

the face just last year. "We [journalists] are always targeted. The government covers up for them, and

there is no punishment. They should

be punished. The police knew that

the JCD was going to attack."

Altaf Hossain Choudhury, who,

as home minister, was in charge of

internal security at the time of the

attack, has a different perspective.

Choudhury, who has since been

reassigned to the Commerce Ministry,

believes that journalists who cover

demonstrations do so at their own

risk because police and other

authorities cannot distinguish

between the press and protesters.

"The police are just doing their job,"

Choudhury says. Local photographers disagree and say they are well

known in town as journalists.

According to the photographers,

their cameras and equipment make

them stand out in a crowd, and the

JCD targets them to keep news of

the group's violent attacks out of

the press.

D

haka University is in the center

of the capital, and it is on the

front lines of Bangladesh's turbulent

political life. It is the frequent scene

of rallies and clashes, which the

press widely covers. The campus

played a key role in Bangladesh's liberation war from Pakistan in 1971,

when radical students fought the

Pakistani army, which shelled the

university and massacred many students and intellectuals in response.

Student support is considered to

be such a priority for Bangladesh's

political factions that both main parties—the ruling BNP and the opposition Awami League (AL)—formed student wings and youth leagues dedicated to garnering student votes.

The student groups in turn utilize "street muscle" to enforce their

will, both on campuses and in towns

throughout the country, employing

armed thugs and older political

activists. According to Dr. Kamal

Hossain, a leading lawyer, human

rights activist, and one of the

authors of Bangladesh's 1972 constitution, this practice dates back to the

1980s—and it has unfortunate consequences for the press.

"Young armed thugs, unemployed youth, were drafted for the

purpose of manipulating elections,

enhancing their power as they go

along, serving their patrons and

themselves, evolving into systematic

extortion, even institutionalized

extortion, because the police are getting a share, too," says Hossain. "The

main targets of these groups are the

journalists who expose this."

Among the targets is 25-year-old

Hasan Jahid Tusher. As a master's

student of journalism and the Dhaka

University correspondent for the

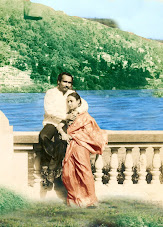

Under the governments of both former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina (left) and

current Prime Minister Khaleda Zia (right), violence against journalists in Bangladesh

has continued with impunity.

AP/Pavel Rahman

AP/Pavel RahmanEnglish-language The Daily Star,

Tusher used to live on campus and

covers the lively political scene

there, including the violent activities

of the BNP's student wing, the JCD.

On May 8, 2003, Tusher wrote about

a group of JCD activists who had

allegedly beaten a student for refusing to obey their orders.

After the story was published,

Tusher says he began receiving

threats from the group's leaders in

his dormitory demanding that he

stop writing about their activities on

campus, but he continued reporting

on the JCD. On the night of July 31,

2003, a group of 20 JCD activists ransacked Tusher's dorm room and beat

him severely with iron rods and

sticks before dragging him down

three flights of stairs and leaving

him outside the dormitory. Students

brought Tusher to a hospital, where

he was treated for injuries to his

shoulders, back, and arms.

The attack caused outrage on

campus, but little was done to punish those responsible. Four of his

assailants were expelled from the

JCD but allowed to remain on campus. Although members of the Dhaka

University Journalists' Association

said that, based on his earlier threats

against Tusher, the head of the dormitory's JCD unit, Tanjilur Rahman,

was responsible for ordering the

attack, Rahman was never punished.

Tusher decided to move out of his

dorm after the incident. "All the time

on the campus we have to be careful

about our movements, especially

me," says Tusher. "Sometimes I feel

insecure and am afraid of the JCD

and the people around them."

T

wo months after journalist Shafiul

Haque Mithu was almost killed in

a brutal attack, he is still in pain from

the head and arm injuries inflicted

on him by local BNP activists. Mithu,

the local correspondent for the popular Bangla-language daily Janakantha,

is from Pirojpur, a town 100 miles

(160 kilometers) south of Dhaka in

one of Bangladesh's infamous southwestern districts, which are known

for violence against journalists and a

lack of law and order.

One editor calls the area "the valley of death." Five journalists have

been killed there in the last four

years in retaliation for their reporting, including Manik Saha, a veteran

journalist with 20 years' experience

who was murdered in January 2004

by a homemade bomb in Khulna, a

neighboring southwestern division.

Criminal organizations dominate

the towns of rural Bangladesh and

target the journalists who try to

expose them, according to lawyer

Hossain. "Local criminal networks

with political bosses have institutionalized a structure of terror in the

countryside," explains Hossain.

"They are predatory groups, the

more violent crime pays, and their

patrons want more wealth."

In December 2003, Mithu reported

a two-part series about a criminal

gang in Pirojpur that was abusing

and terrorizing the local Hindu

minority community in an effort to

take over their valuable lands. In the

articles, Mithu detailed how the criminals, allegedly under the protection

of local BNP officials, looted valuable

fishponds and forcibly took over 85

acres of land from the Hindu community. When the local residents

tried to resist, the criminals beat

them severely.

After the first article ran on

December 17, a group of BNP

activists began following Mithu and

threatening him. Local BNP members

16 Spring | Summer 2004

Criminal organizations dominate the towns of

rural Bangladesh and target the journalists who

try to expose them.

AP/Bappy Khan

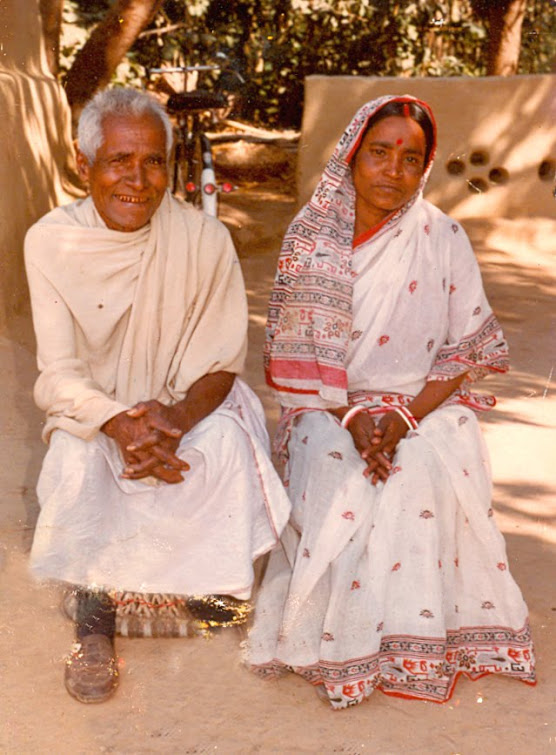

Family members of veteran journalist Manik Saha, who was killed by a homemade

bomb in January 2004, mourn in his hometown of Khulna, 85 miles (136 kilometers)

outside the capital, Dhaka.Dangerous Assignments 17

of Parliament and political leaders

denied the story and publicly

denounced the journalist. They even

formed a commission to prove that

his reporting was false, says Mithu,

but were unable to refute the evidence

in his story.

When the second part of the series

ran two weeks later, on December 28,

the BNP activists made good on their

threats. Mithu was attacked on his

way home from the Pirojpur Press

Club by a group of thugs, including

local BNP activists, who trailed him

and then ambushed him. The three

assailants then tried to kill Mithu,

beating him in the head repeatedly

with pipes, knocking him unconscious, and breaking his right arm in

several places. Fortunately, when

local passersby heard his

cries and came upon the

scene, they saved Mithu.

His assailants tried to flee,

but one of them, a local

thug known simply as

Russell, was captured.

Mithu has identified two

other assailants in the

group as BNP activists

Chowra Kamal and Akram

Ali Molla.

"There is a culture of

protection and patronage

for people who indulge in

violence," explains Hossain.

"Police are prevented from

taking action against them

because they enjoy protection. Courageous journalists are among the leading

targets, particularly journalists working outside

the capital."

Authorities arrested

Russell and charged him

with attempted murder in

March 2004. Kamal and

Molla were officially

charged with attempted

murder later that month,

according to The Daily Star.

But they remain at large

and have not been arrested

even though they have been publicly

sighted in the Pirojpur area at political

meetings.

Mithu doubts that police will

apprehend those responsible for the

attack because local political leaders

from the JCD, BNP, and the Islamic

fundamentalist party Jammat-i-Islami

oversee the local police station and

use the police as their "muscle,"

according to Mithu.

After the attack, locals brought

Mithu to a hospital for treatment, but

he still suffers from severe headaches and pain in his right arm,

which has not yet been properly set.

He is scheduled to travel to India for

treatment on his arm in the coming

months. Currently, he lives in Dhaka

with relatives because he says it is

too risky back home in Pirojpur.

Even before he was attacked,

Mithu says he was constantly under

threat from BNP activists and Jammat members because of

his reporting. In July 2003,

he was one of seven journalists in Pirojpur to

receive anonymous death

threats by mail. Pieces of

white cloth cut from what

appeared to be a funeral

shroud were sent to the

journalists with notes

threatening them to stop

reporting on criminal acts.

T

he current climate of

violence for the Bangladeshi press does not

reflect its history, journalists say. According to The

Daily Star's editor and publisher, Mahfuz Anam, during the colonial era, Bangladesh had one of the most

outspoken, anticolonial

presses in the region. Under

the subsequent rule of Pakistan, from 1947 to 1971,

the local Bangladeshi media

carried strong anti-Pakistan coverage. The turning point for the press

came in 1991, when the

country held its first democratic elections after

enduring a series of miliSeven journalists received threatening notes,

along with pieces of white cloth cut from a

funeral shroud.

A local thug known simply as Russell poses for a mug shot

after being captured and identified as one of the assailants who

brutally beat journalist Shafiul Haque Mithu in December 2003.

Photo courtesy Zahirul Haque MithuJustice Delayed

The case of Tipu Sultan

By Abi Wright

W

hen journalist Tipu Sultan was brutally beaten and left for dead

on the side of a road in January 2001, it quickly became clear who

was responsible for the attack. According to Sultan, one of the

assailants told him that Joynal Hazari, a Parliament member from the

Awami League (AL), which controlled Parliament at that time, had ordered

the beating in retaliation for Sultan's reporting on Hazari's many abuses

of power.

But little was done to bring Hazari to justice. Despite the mounting evidence, then Prime Minister and AL leader Sheikh Hasina doubts the facts.

"I am not 100 percent certain [that he is guilty]," she said in a recent interview. "Even in the Parliament, Hazari denied it."

In October 2001, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) unseated the

AL. Before the vote, BNP leader Khaleda Zia promised to prosecute Sultan's

attackers if elected. But more than three years later, both of the country's

political factions have failed to resolve Sultan's case. And in the absence of

any resolution, Sultan remains at risk, regularly receiving threats from

18 Spring | Summer 2004

tary dictatorships and bloody coups

from 1975 to 1990.

The BNP's slim victory in the

1991 election caused deep resentment among the AL leadership and

engendered pronounced political

divisions across the country. These

tensions are responsible for much of

the political violence against the

media today, according to Anam.

"The restoration of democracy was a

springtime for the press." But since

then, "there has been a failure of governance, and a blaming of the press

for these shortcomings."

During the rule of AL leader

Sheikh Hasina from 1996 to 2001,

journalists in Bangladesh also suffered dozens of violent threats and

physical attacks. In 1999, the

Janakantha office in Dhaka had to be

evacuated after an anti-tank mine

was left in the lobby of the building.

Although the mine was removed

before it detonated, it could have flattened a city block if it had exploded,

says Mohammed Masud, the paper's

publisher. And in January 2001, wire

service reporter Tipu Sultan was

brutally beaten on the orders of AL

parliamentarian Joynal Hazari. (See

sidebar on this page.)

Although many popular Bangladeshi dailies in the capital, such as

The Daily Star, Prothom Alo, and

Janakantha, run critical articles and

even political cartoons about the ruling BNP government on their front

pages without direct or violent

reprisal, independent dailies still feel

pressure from the government, says

Masud. In retaliation for critical

reporting, Janakantha reporters have

been denied access to government

officials, the current government has

withdrawn advertising money from

the newspaper, and an angry mob

attacked and tore down a wall outside

Masud's home last summer.

In addition, the bitter rivalry

between the two majority parties

and their leaders, ruling BNP Prime

Minister Khaleda Zia and opposition

AL leader Sheikh Hasina, has conBangladeshi journalist

Tipu Sultan in Dhaka

in June 2003, two-and-ahalf years after he was

brutally attacked AP/Pavel RahmanDangerous Assignments 19

Hazari. It seems that in Bangladesh, it doesn't matter who is in power—

violence against journalists remains acceptable.

Sultan's troubles began on the night of January 25, 2001, when a group

of armed men kidnapped the journalist in Feni, in southeastern Bangladesh.

The gang savagely beat him with iron rods and hockey sticks, breaking

bones in his hands, arms, and legs. The assailants specifically maimed Sultan's

right hand—his writing hand—and the beating left a gaping wound in his

right arm. (See Dangerous Assignments, Summer 2001.)

According to Sultan, because the local police chief was known as "Hazari's

man," police did not allow Sultan to file charges against Hazari immediately

following the attack. Hazari's supporters, however, did file a false case

charging rival political activists with orchestrating the assault. In September 2001, after Awami League leader Hasina had stepped down before

national elections, Sultan was finally able to file a local police report against

Hazari. But by then, Hazari had gone into hiding, reportedly in India.

After a 28-month investigation, Hazari and 12 associates were charged

with attempted murder in absentia in April 2003. Hazari was formally

indicted in October 2003, and the trial began in a local district court in

Feni on November 5, 2003. Sultan testified against Hazari in December, but

the legal proceedings were soon derailed when two of the accused men

filed separate petitions in the High Court to quash Sultan's case. The court

agreed to review their petitions on January 26, 2004, postponing the trial

for six months.

Sultan appealed to Law Minister Moudud Ahmed for help in February,

and in an interview with CPJ in March, Ahmed said the attorney general had

already been instructed to submit an application for an expeditious hearing

in Sultan's case.

Although Sultan is back at work as a reporter for Prothom Alo, the

country's the largest Bangla-language daily, he is continually reminded of

that horrible day three years ago. Hazari may be out of the country, but he

is not far enough away to stop threatening the journalist and those associated with his case. Hazari called Sultan in August 2003 saying he would kill

the journalist and his family unless he withdrew the case, according to Sultan.

One of Sultan's key eyewitnesses, Bakhtiar Islam Munnah, the local correspondent for the daily Ittefaq, has also received threats from Hazari and

was attacked twice last year. These attacks have made other witnesses "feel

insecure," says Sultan.

And the lack of action from Bangladesh's current and previous administrations hasn't made things any better. Today, the case remains bogged

down in legal delays, and only one of the 13 men accused in the attack is

currently behind bars; six remain at large, including Hazari, and six of them

were freed on bail. "We are doing everything we can for Tipu," says government

minister Altaf Choudhury. But as long as Hazari remains free and Sultan's

trial is postponed, Bangladeshi journalists remain at risk. n

tributed to the growth of a culture of

violence in Bangladesh. "We have seen

an increasing dependence on criminal forces to thwart opponents and

get votes. Known criminals are nominated for Parliament," says Anam,

and that adversely affects the press's

development. "Independent journalism was growing, while politics

became more criminal."

Even the journalists themselves

are divided in Bangladesh. All of the

country's journalists' unions, from

the national level to the local level,

are split in two along party lines;

there is a BNP-affiliated Bangladesh

Federal Union of Journalists (BFUJ),

and an AL-affiliated BFUJ.

After the BNP retook power in

2001, a group of 27 journalists from

the state-run news agency Bangladesh

Sangbad Sangstha (BSS) were summarily fired because they were considered to be affiliated with the AL.

BSS soon hired 40 new people for the

jobs and refused to rehire the 27

journalists even after a court ruled

that they had been illegally fired and

ordered their reinstatement. Many of

the 27 journalists remain angry at the

BNP. "This was an illegal termination,

and a violation of normal procedure,"

says Haroon Habib, one of the dismissed journalists.

A

lthough journalists in Bangladesh

remain vulnerable because threats

and attacks go unpunished, few in the

government are willing to take responsibility. Prime Minister Zia told Parliament on March 17 that Bangladeshi

journalists "enjoy full press freedom,"

and that when journalists are attacked,

it is "for other local-level reasons, and

not for journalism."

None of this comforts photographer Chowdhury. From his hospital

bed in a cramped room, he sounds

resigned to his fate as a journalist in

Bangladesh. "In this climate, the

political situation will get worse

again," he sighs, "and I'll go out and

cover what's happening again, and be

at risk again." n20 Spring | Summer 2004

W

hen we visited her headquarters in Bangladesh's

capital, Dhaka, in early March, Sheikh Hasina,

leader of the country's opposition Awami League

(AL), handed our CPJ delegation a long list of press freedom

abuses. On top was the gruesome photo of journalist Manik

Chandra Saha's decapitated corpse, taken shortly after someone tossed a homemade bomb at him in January.

A day after our talks with the Awami League, we met

with Bangladesh's information minister, where another list

awaited us. This one gave the government's version of the

press freedom story, a litany of abuses committed from

1996 to 2001, the period of AL rule until its election defeat

by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP).

Taken together, the AL and BNP lists are testimony to

the dangers encountered by Bangladeshi journalists, who

are just doing their jobs. The lists also support one of the

conclusions stated by CPJ's delegation at the end of its visit:

"It takes real courage to be a journalist in Bangladesh."

But the two lists also reveal another hard reality in

this deeply politicized country. The BNP points to press

freedom abuses committed during the AL's tenure in

office, but not a single incident since the BNP took power

in 2001. Meanwhile, the AL's document would have the

public believe that threats and violence against journalists began only in 2001, under BNP rule.

State media play the same political game. After sitting

through a sometimes contentious meeting between CPJ

and officials from the Bangladeshi Information Ministry, a

reporter for the government's mouthpiece news agency

wrote about the information minister's claim that, "We do

highly respect the right of expression and free flow of

information." Missing from the report was any mention of

CPJ's detailed research presented to the minister documenting that killings, beatings, threats, and harassment

of the media are commonplace in Bangladesh, regardless

of which party is in power.

State media also ignored CPJ's protests against the

government's heavy surveillance of our delegation's

movements, including tailing us to nearly every meeting

and eavesdropping on conversations with journalists

who met us at our hotel. A reporter from a privately

owned newspaper who phoned to confirm details of the

government's surveillance of CPJ revealed that, "They've

done that to me, too." His paper and others reported at

length on CPJ's findings and our call for vigorous investigations and prosecutions of all those who murder,

assault, or threaten journalists in Bangladesh.

But despite these few feisty, independent media outlets, deep and bitter divisions between Bangladesh's two

main political parties permeate institutions throughout

the country. These include the courts and even the media

and the unions that represent journalists.

In 2002, in a decision widely viewed as orchestrated

by the BNP government, a Bangladeshi court ordered the

private Ekushey Television (ETV) off the air for technical

violations in its license application. ETV provided viewers

with popular and professional news and public affairs

programming, but the government refused to approve its

application to renew broadcasting. ETV employees say it

looks unlikely that they will go back on the air as long as

the BNP remains in power.

Some journalists in Bangladesh have protested the

blatantly political silencing of ETV. But not Gias Kamal

Chowdhury, president of the Dhaka Union of Journalists.

Chowdhury was a co-sponsor of the complaint that led

to the court-ordered shutdown. When our delegation met

with him, we asked why a journalist—particularly the head

of a professional union—would want to see the closing of an

independent media outlet admired for its professionalism.

Chowdhury says that while he is a journalist, he is also a

citizen of Bangladesh and cannot countenance a TV station

operating with a flawed application.

T

he politics that keep ETV off the air also thwart justice

in the dozens of cases of assaults on Bangladeshi

journalists. The government's failure to prosecute these

crimes only encourages more, and bolder, attacks.

Particularly shocking was last January's assassination

of Manik Saha, whose tough reporting helped his readers

understand the sinister web of corrupt politics and organized crime in southwestern Bangladesh. That region is

notorious for its crime, and young journalists at provincial newspapers there are among the very few brave

enough to investigate the mafia-like operations.

"We know the names of all the godfathers because of

them," says lawyer Kamal Hussein, referring to the small

band of provincial journalists willing to publicly name

those criminals. Hussein has defended some of

Bangladesh's courageous journalists, and he tells CPJ that

what is needed most to protect them are credible, independent investigations of crimes against the press.

Manik Saha's assassination "is clearly a message, because

he was kind of the dean of all these courageous journalists,"

says Hussein. Without justice in the case of Saha and others,

predicts Hussein, investigative journalism in Bangladesh

could become endangered, or even disappear. n

Real Courage

by Ann Cooper

No comments:

Post a Comment