A FEW MORE DEATHS IN THE GRANARY THAT FEEDS BENGAL | ||

| Farmers continue to take their own lives in Burdwan. Uddalak Mukherjee examines some of the causes, even as the government disputes these deaths | ||

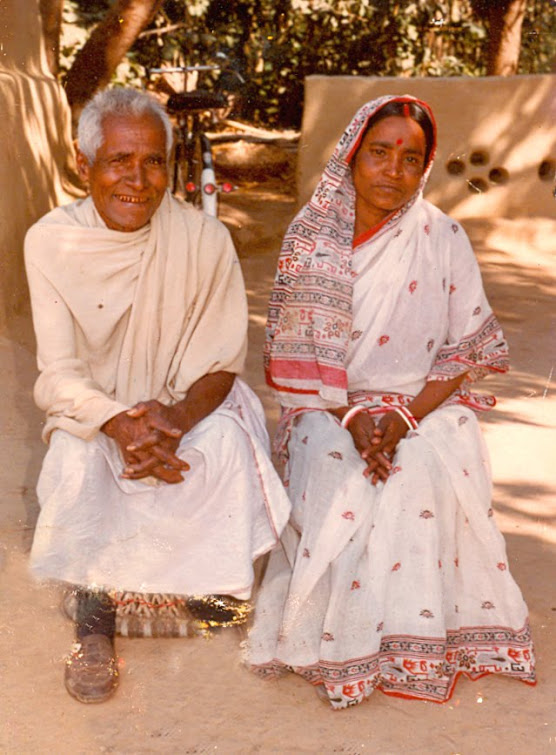

Two years ago, I had travelled to Ausgram in Burdwan to examine how the absence of a robust rural banking system and the dominance of unscrupulous moneylenders had forced a number of farmers to take their own lives. Last week, I returned to Burdwan — this time to Kaltikuri village in Bhatar block— where 10 farmers have committed suicide since November last. Similar deaths have been reported from Birbhum, Bankura and Malda, while the South 24 Parganas has recorded 11 deaths. My second visit to the district was prompted by three developments. First, the latest report published by the National Crime Records Bureau on farm suicides between 1995-2002 and 2003-2010 has declared that among all the states in India, West Bengal has registered the biggest decline in such deaths. Between1995-2002, 1,426 farmers had died. The figure fell to 990 in the next 8 years, registering an average decline of 436 deaths. The report was published sometime in December 2011, and, ironically, coincided with the first phase of the fresh spell of suicides that continue to haunt West Bengal. What must be remembered, though, is that a number of these deaths remain unreported or are disputed by the government. 'Mental depression', 'debt' and 'alcoholism' are some of the reasons that the government has cited to account for the deaths. The new government has announced several institutional measures to ensure that paddy farmers are able to sell their produce at the government approved minimum support price: Rs 1,080 and Rs 1,110 per quintal for coarser and finer varieties of rice, respectively. Farm agencies such as Benfed, Confed and the Essential Commodities Supply Corporation have been directed to set up procurement camps in the district. Rice mill owners have been instructed to pay farmers in cheques to minimize the involvement of middlemen— colloquially known as phore or aratdar. The government has also announced that 20 lakh tonnes of paddy will be procured by September. My second reason for visiting Burdwan was to investigate whether these institutional measures are adequate when faced with a crisis. The third reason was to explore the possibility that the government and the media were showing a limited understanding of the complicated structure of an agricultural economy and the resultant contradictions that are integral to it. There has been a sustained campaign to implicate, and hence demonize, phores and rice mill owners in the farmers' plight without taking into cognizance the fact that both phores and mills — the allegations of irregularities notwithstanding — play a critical role in the sustenance of the farming community in the absence of credit institutions and access to a ready market. Incidentally, Kanchan Ruidas, a middleman, had hung himself in Galsi block after his business suffered irreparable losses. So it is not as if middlemen have remained immune to debt. In Kaltikuri, I first met a group of cultivators led by S.K. Nurul Islam at the house of Safar Mollah, a paddy farmer who had killed himself in November. In the course of the discussion with the farmers in Kaltikuri and, later, with the secretary of the Burdwan District Rice Mills Association, what emerged was the fact that the present crisis has been aggravated by three factors, each of which needs to be scrutinized in detail. The first, as mentioned earlier, refers to crippling deficiencies in the institutional response. On January 5, the agriculture minister had promised that the government would bear the cost of transporting paddy to procurement camps. A day earlier, the food department announced that 400 camps would be established to procure paddy, while the chief minister ordered the relevant departments to work on a war footing to expedite the distribution of Kisan cards and the setting up of mandis. In Kaltikuri, I was offered a glimpse into how far such promises have been met on the ground. None of the farmers has received any financial assistance to travel to the procurement centres. The first and only time a procurement camp was organized in the village was in early February. The government's campaign to raise awareness about the camps has been as dismal: the reason for the low turn-out of farmers in the procurement camps in Galsi and Bhatar can be attributed to this factor. The effectiveness of these camps has been further compromised by the regulations that guide them. The number of sacks of rice that can be sold in a particular camp is decided by the bureaucracy, which, like the government, has very little idea about the character and needs of the local farming community. Thus, in the camp set up in Kaltikuri in February, only 200 sacks of paddy were bought. This meant that in this village of a hundred families, in which even a marginal farmer owns 20 sacks of paddy, each household could sell only two sacks of paddy. The financial crunch faced by farm agencies has meant that some of Kaltikuri's farmers are yet to receive the cheques for the paddy that they sold in February. The Union food secretary's useful suggestion of involving primary agriculture credit cooperative societies (PACCS) in the procurement of paddy on a commission basis, a model that has been implemented with great success in states such as Punjab and Haryana, has perhaps remained on paper. As for measures such as Kisan cards — greatly favoured by the chief minister as well as by Nabard as an instrument for dispensing farm credit — they are yet to become popular with farmers. This is because such loans, I was told, are disbursed in three separate installments. This means that farmers are forced to depend on traditional sources of credit — moneylenders and middlemen — especially at the beginning of the boro oraman seasons, to buy seeds and fertilizers. An added advantage of the local system of credit in the farmers' eyes is its accessibility and the absence of the dreaded red tape. To avail of loans from the government, several visits to the supremely inefficient block land record office are mandatory. The acceptance and popularity of the mahajan, phoreor aratdar, who is often a relative or a neighbour, can be located in such affiliations as kinship, caste and community, something that is yet to be recognized by the government in a state that has, reportedly, 10 lakh farmers without access to bank loans. These institutional shortcomings expose several other lacunae in the government's farm policy. In December last, it was reported that the Bengal government was yet to renew the Centrally-aided Weather-Based Crop Insurance Scheme that would have benefited not less than 50,000 farmers who are entitled to receive Rs 5,000 per acre on account of crop loss due to adverse weather. A party that came to power pledging to secure the interests of farmers has shown a marked unwillingness to bear this not-too-extravagant cost. The state government has also failed to check the infiltration of finer varieties of rice from states like Andhra Pradesh and Chhattisgarh that has pushed down prices in Bengal. In the open market in several districts, 60 kilogrammes of rice are being sold at Rs 470. The crisis in Bengal has been aggravated by a good harvest in Bangladesh, one of the key markets for Bengal's rice farmers, as also by Bangladesh's decision to import rice from Myanmar. One wonders whether the chief minister's intransigence regarding the sharing of Teesta's waters has something to do with Bangladesh's disinclination to import rice from Bengal even after the lifting of trade restrictions. But perhaps the most glaring instance of the government's myopic farm policy is its instruction to rice mill owners not to procure paddy from middlemen. This community of traders has traditionally served as a critical conduit between farmers and rice mills, buying paddy from farmers, admittedly at much lower rates, and then selling the produce to the mills, which, in turn, sell the grain to the government. A better understanding of the inner dynamics of an agrarian economy would have prompted the government to co-opt the community of middlemen in its drive to provide farmers with a fair price. The middleman's utility lies in his personal access to farmers. The government could have utilized his services in reaching the minimum support price to farmers by putting in place a system of commission for the trader. The lure of government commission, together with the threat of stringent penalties for cheating farmers of the minimum support price, could have encouraged middlemen to trade in a fair and transparent manner. Additionally, it would have spared the government the trouble of nudging hesitant banks to do business in villages and of setting up ineffectual procurement camps. The established structure and rituals of an agrarian society would have also remained secure. The loss of the services of the middleman and pressure from the government have put the rice mills in a quandary as well. The depletion in stocks as a result of the loss of supply from middlemen has adversely affected their business. It has also forced mills that traditionally traded in finer varieties of grain to purchase coarser alternatives that have few buyers. For instance, a rice mill in Burdwan that traded in gobindobhog,kaminibhog or tulaipanji is now being forced to buy grain of inferior quality. The mills' inability to sell their stock can also be traced to the lack of space in government godowns that are yet to clear last year's produce. Dwindling profits have resulted in some mills issuing cheques that have not been honoured by banks, inconveniencing farmers further. The farmer, the trader and the rice mill are parts of the same continuum. Any regressive step that is likely to disturb one particular segment in this chain would impair the other segments as well. But the agrarian policy remains indifferent to these facts. What is also ignored is that the agricultural crisis has been compounded by the changes in the character of farming practices. India's search for food security and the subsequent success of the Green Revolution have resulted in the government according greater priority to the school of farming that encourages high yields. This includes features such as an indiscriminate use of chemical fertilizers and greater corporatization. These are preferred over the school that is characterized by diverse, sustainable and ecologically sensitive practices. The consequences of such a transformation are evident among the farmers in Kaltikuri. Five years ago, in this village, the average yield of paddy was 11 quintals per bigha. This yield required the application of, approximately, 20-25 kgs of chemical fertilizers per bigha. The cost of urea then was Rs 240, while the price of diammonium phosphate was Rs 450. Five years later, the average yield per bigha has fallen to 6 quintals. Nearly 70-75 kgs of fertilizers are being applied. Urea costs Rs 360 now, while the price for DAP has risen substantially. This makes it fairly evident that despite the substantial use of chemical fertilizers, there has been a corresponding drop in agricultural output, which is indicative of an alarming dip in soil fertility. The lack of government subsidies in fertilizers has eaten into the farmers' profits. The rush to produce cash crops in the hope of quicker profit has also resulted in changes in cropping patterns. Farmers who once took pride in growing rice varieties such as doodhkamla, jhingasaal or banslagra are now cultivating high-yielding variants that require greater investments in chemical fertilizers. Perhaps the debate about the introduction of foreign direct investment in India's agrarian sector needs to consider these specific aspects of the argument. The experience of potato farmers in Raina with contractual farming with a multinational giant has led cultivators in other areas of the district to believe that the privatization of agriculture can cure their plight. Their hopes are based on such promises as those of a ready market, an assured income, better seed quality, guidance regarding the preservation of soil fertility, and so on. But the question of farmers retaining their autonomy instead of being reduced to a collateral agency under such a contractual model must be addressed. For instance, would a farmer be able to exercise choice over the kind of crops that he wants to grow? (At present, the farmers in Raina only grow a variety of potato that is used to manufacture wedges and chips.) Would the profits be distributed equitably between the company and the farmers? Would such an output oriented model of farming end up replicating the ecological crisis that is a corollary of the farming practices that are in operation at present? Significantly, the farmers, at least the ones I met, are keen to fight back against the government's apathy in a novel manner. The villagers would elect candidates in the forthcoming panchayat elections by disregarding political lines in the hope of constituting a truly apolitical body. They believe that only this — and not the deaths of farmers —would force the chief minister to intervene. |

Current Real News

7 years ago

No comments:

Post a Comment